Breadcrumb

- Wallace

- Reports

- Learning From Summer Effects Of ...

Learning from Summer

Effects of Voluntary Summer Learning Programs on Low-Income Urban Youth

- Author(s)

- Catherine H. Augustine, Jennifer Sloan McCombs, John F. Pane, Heather L. Schwartz, Jonathan Schweig, Andrew McEachin, and Kyle Siler-Evans

- Publisher(s)

- RAND Corporation

- DOI Link

- https://doi.org/10.7249/RR1557

Summary

How we did this

The report presents findings on the effects of two consecutive summers of programming in 2013 and 2014 on language arts and mathematics learning. It also evaluates student behavior and social-emotional competence in the fall after each summer program and through spring 2015. Methods included a randomized controlled trial. At the start of the effort, the participating children were rising fourth graders.

Low-income students who attend well-designed summer learning programs at high rates reap meaningful educational benefits in math and reading.

That’s the central finding discussed in this report. It looks at a groundbreaking study assessing large-scale, voluntary, school district-run summer learning programs and how effective they are. Launched in 2011, the multi-year research project evaluated the outcomes of programs in five urban districts. The goal: to find out whether and how voluntary-attendance summer learning programs combining academics and enrichment could help students succeed in school.

Can Summer Programs Help Shrink the Summer Learning Gap?

Children from low-income families typically lose ground in learning over the summer compared with their more affluent peers. One way to help shrink the gap is through voluntary, school district-run summer programs combining academics and enrichment. They also can potentially reach more students than traditional summer school or smaller-scale programs run by outside organizations.

Until this effort, the National Summer Learning Project (NSLP), was launched, little if any long-term, broad-based research had been done on the impact of these programs and the keys to their success. The NSLP sought to address that knowledge gap.

The project, sponsored by The Wallace Foundation, centered on the work of five urban school districts and their partners. They set out to run high-quality summer learning programs that offered a mix of academic and enrichment.

Randomized Controlled Trials

In 2013, researchers conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in the districts—Boston; Dallas; Duval County, Fla.; Pittsburgh; and Rochester, N.Y.—to evaluate educational outcomes. They focused on children who were in third grade in spring of that year.

The 5,600 students who applied to summer programs were randomly assigned to one of two groups. One comprised those selected to take part in the programs for two summers (the treatment group). The other comprised those not selected (the control group). The study analyzed outcomes for 3,192 students offered access to the programs.

Key Findings

Major findings included:

- Those who attended a five-to-six-week summer program for 20 or more days in 2013 did better on state math tests than similar students in the control group.

- This advantage was statistically significant and lasted through the following school year.

- The results are even more striking for frequent attenders in 2014. They outperformed control group students in both math and English Language Arts (ELA), on fall tests and in the spring.

- The advantage after the second summer was equivalent to 20-25 percent of a year’s learning in math and ELA.

- About 60 percent of students attending at least one day met the 20-day threshold that was defined as high attendance.

These findings are correlational. But they were controlled for prior achievement and demographics. As a result, researchers were confident that the benefits were likely a result of the programs’ impact.

High-attending students were also rated by teachers as having stronger social and emotional skills than the control group students. Researchers, however, were less sure this was because of the programs. That’s because they lacked prior data on these competencies.

An unrelated RAND Corp. report later reviewed research about summer learning programs and their effectiveness. One aim was to find those that met specifications for evidence rigor under the federal Every Student Succeeds Act. RAND found 43 programs that met these specifications. The NSLP was among them and one of the few that ranked in the highest level of evidence rigor.

Effect of Being Offered Access

Separately, the study also examined the impact of the programs on all students who were offered access, whether or not they attended.

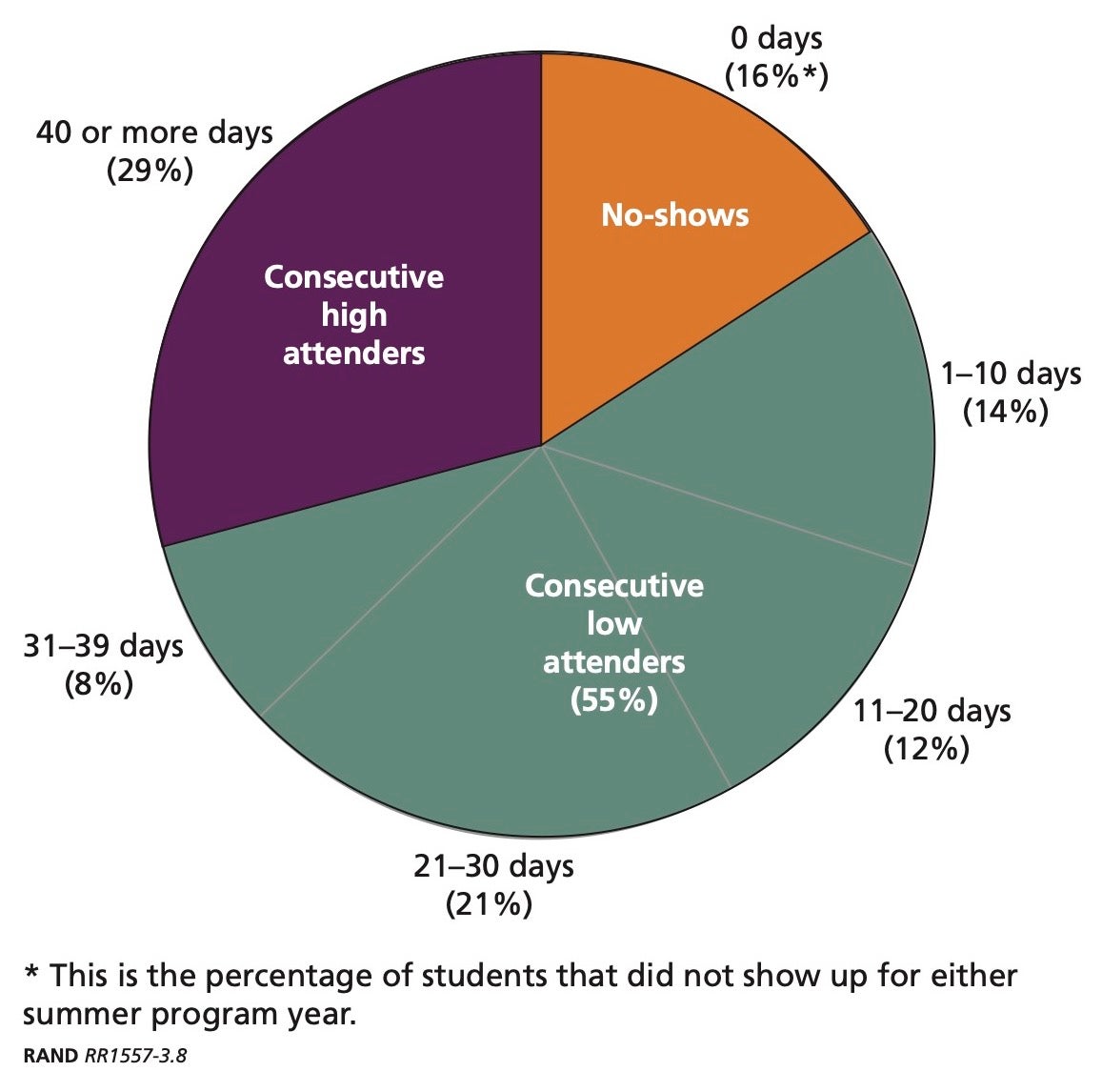

Many students did not attend at a high level, and some didn’t show up at all. As a result, the average benefits for all of these students were smaller and not statistically significant. However, there was a modest, but educationally meaningful, boost in math scores in the fall after the first summer. It was equivalent to 15 percent of a year’s learning.

Recommendations for Practitioners

For students to experience lasting benefits from attending summer programs, the report recommends that districts take the following steps:

Run programs for at least five weeks. Because higher attendance rates resulted in better outcomes, the report recommends that similar programs last for at least five weeks—and ideally six or more—with a minimum of three hours of academics a day.

Promote frequent attendance. That should include offering programs to multiple grade levels to prevent older siblings from needing to care for younger children. Also important: making personal connections with families of students who may be more prone to infrequent attendance and establishing mandatory programs for the lowest-performing students.

Include enough instructional time—and protect it. Program leaders can do that by avoiding scheduling breaks and special activities during academic blocks.

Invest in instructional quality. That means recruiting summer teachers with subject and grade-level experience: They’re often better able to connect the content to previous or upcoming school-year lessons. Teachers should also take the time to ensure all students understand the academic material.

Lower costs by factoring in attendance and likely no-show rates. Districts can reduce their budget for summer programs by using realistic projections to make decisions that are based on student numbers.

Key Takeaways

- Those who attended a five-to-six-week summer program for 20 or more days in 2013 did better on state math tests than similar students in the control group.

- They outperformed control group students in both math and English Language Arts (ELA) on fall tests and in the spring.

- Researchers recommend that districts invest in instructional quality by recruiting summer teachers with subject and grade-level experience.

- Districts can reduce their budget for summer programs by using realistic projections to make decisions that are based on student numbers.

Visualizations

Days Students Attended Summer Programs in 2013 and 2014

Materials & Downloads

What We Don't Know

- What was the level of students’ social and emotional skills before the research began?

- How much of the intended content did students learn during the summer?

- The programs provided many students with opportunities they may not have had otherwise, such as swimming, rock climbing and cooking. How did these experiences influence students and their families?