Breadcrumb

- Wallace

- Reports

- Investing In Successful Summer P...

Investing in Successful Summer Programs

A Review of Evidence Under the Every Student Succeeds Act

- Author(s)

- Jennifer Sloan McCombs, Catherine H. Augustine, Fatih Unlu, and Kathleen M. Ziol-Guest

- Publisher(s)

- RAND Corporation

- DOI Link

- https://doi.org/10.7249/RR2836

Summary

How we did this

Researchers reviewed evaluations of summer programs in the United States serving students in the summer before kindergarten through the summer before 12th grade. They conducted a comprehensive search of the major electronic databases of indexed scientific literature and relevant websites to identify evaluation reports. 83 studies that passed all eligibility criteria were then subject to in-depth reviews per ESSA evidence criteria.

The 2015 Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) provided a major source of federal funding for K-12 education programming in the United States. But the law encouraged—and in some cases required—that programs be backed by research demonstrating their effectiveness to be eligible for financing.

With that in mind, this 2019 report provides practitioners, policymakers, and funders information culled from current research about the effectiveness of summer learning programs for children and youth entering grades K–12.

Four Tiers of Evidence

ESSA categorizes research evidence into four tiers of progressively greater rigor. The top three are necessary or desirable for programs to receive funding.

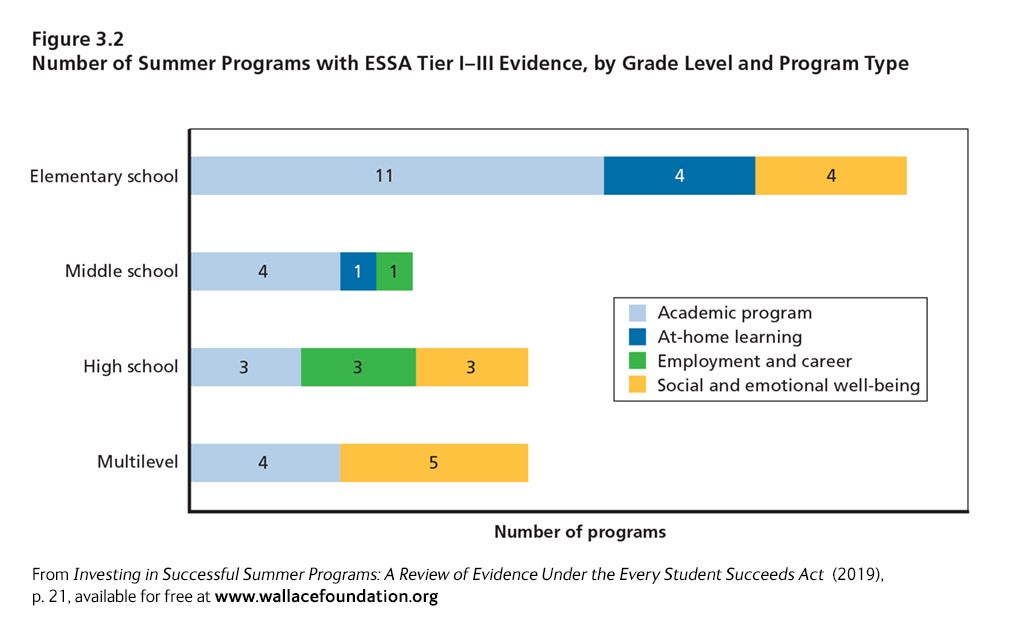

Researchers reviewed elementary-to high-school-age studies about summer programming. They found 43 backed by research strong enough to meet ESSA requirements. The programs targeted an array of goals, from helping kids with academics to providing them with career help.

The publication includes two-page descriptions of all 43 programs and the research findings about their effectiveness.

Key Findings

Summer programs can be effective. Most of the studied programs improved at least one youth outcome. “Decision makers should consider summer a viable time to promote outcomes for children and youth,” the authors write.

A variety of types of programs succeeded. Researchers found evidence that academic learning, at-home learning, social and emotional well-being, and employment and career summer programs improved youth outcomes.

Most of the programs didn’t achieve all their goals. Only 34 percent of all of the measured outcomes were significant and positive.

Programs aimed at improving social and emotional well-being for special groups worked particularly well. That could be tied to the highly focused targeting of the program content to the needs of specific children and youth.

The report includes two caveats about the available research:

Summer learning tends to target academic programs. As a result, it wasn’t possible for researchers to tell whether programs, such as sleepaway camps or physical education, were effective.

Studies frequently measure the impact of a program on its intended goals and other related outcomes. For example, a study might explore the effect of a science program on skills beyond science, like literacy. For that reason, readers should assess how a research finding relates to a program’s intended goal.

Recommendations

The authors make a series of recommendations for funders, researchers, practitioners, and policymakers.

- Decision makers should invest only in certain programs. That means supporting efforts that are designed to address specific needs; are delivered at the right, “dosage,” or number of hours; and can be well implemented.

- Researchers might focus future work on understudied programs. Most research to date has targeted reading achievement. There is less evidence on the efficacy of programs focused on mathematics, science, social and emotional well-being, career preparation, or physical health—all of which might be successfully addressed by summer programs.

- More research should study implementation features. That means information on elements like staff qualifications, cost, training provided, teacher-participant ratios, and participant attendance rates.

Summer is an opportune time to create programs that benefit children and youth, and we find evidence that many types of summer programs can be effective.

Key Takeaways

- Researchers found 43 summer programs for children and teens with research findings strong enough to meet federal Every Student Succeeds Act evidence requirements.

- Most of the studied programs improved at least one youth outcome.

- Evidence shows that a variety of summer programs—academic, at-home learning, employment, and social-and-emotional wellbeing—are effective.

- Decision makers should invest only in programs that are designed to meet specific needs and can be well implemented.

Visualizations

Materials & Downloads

What We Don't Know

What can we expect for program accomplishments over the long-term?

What is the impact of sleep-away camps and other non-academic programs?