Breadcrumb

- Wallace

- Reports

- District Partnerships With Unive...

District Partnerships With University Principal Preparation Programs

Summary of Findings for School District Leaders

- Author(s)

- Elaine Lin Wang, Susan M. Gates, and Rebecca Herman

- Publisher(s)

- RAND Corporation

- DOI Link

- https://doi.org/10.7249/RRA413-6

Summary

How we did this

For the study from which this report is drawn, researchers completed more than 630 interviews, focus groups, and observations from 2017 to 2021. All seven redesign efforts in the University Principal Preparation Program Initiative were examined. That meant exploring the work of university programs, district partners, state partners, and mentor programs. This report looks at key findings pertaining to school districts.

School districts need principals able to raise student achievement. Yet university principal training has not kept pace with the job’s growing demands.

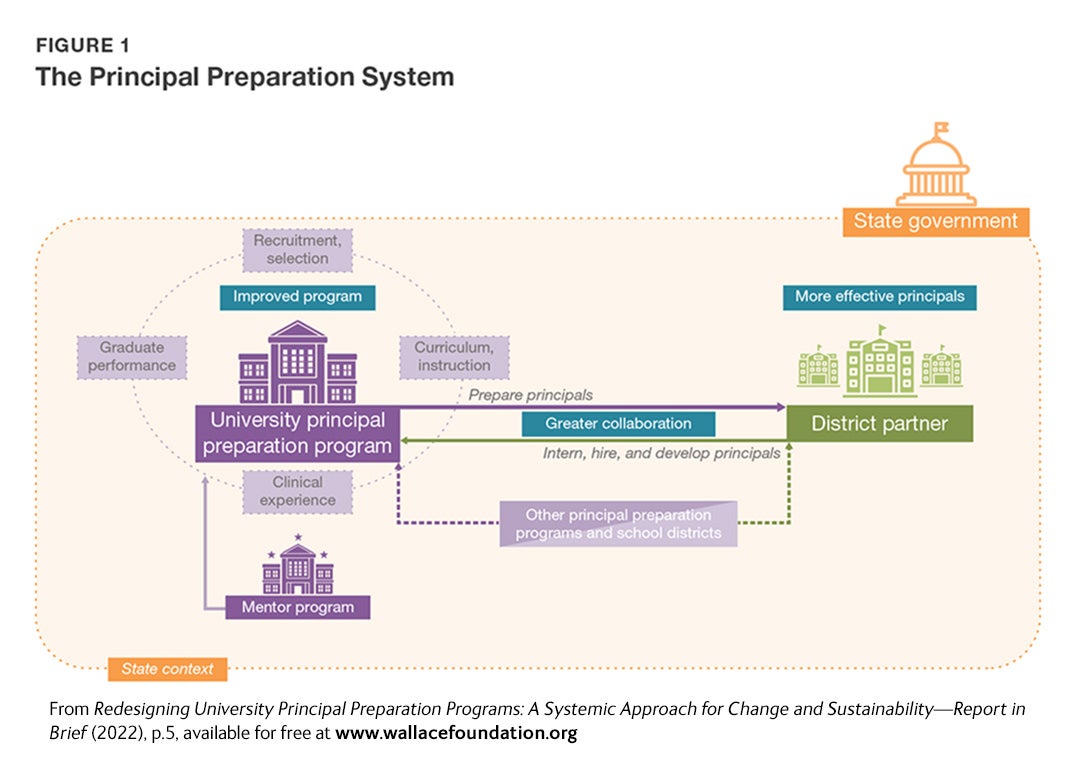

The Wallace Foundation launched an initiative in 2016 to improve principal preparation. Seven universities in seven states participated in the University Principal Preparation Initiative. Universities worked with districts and other interested parties to better align their principal preparation programs with evidence-based practices.

This report summarizes key points for school districts from the RAND Corporation’s full five-year study of the effort.

Major Benefits to Districts

District leaders involved in the effort found the partnerships demanding but worthwhile. There were three major benefits.

1. Principals whose preparation is more closely aligned with district needs. Districts participated in recruiting and selecting candidates for university preparation programs. District officials believed this resulted in stronger candidates entering the program. They also thought it resulted in graduates more likely to return and work in the district. By helping to shape the programs, districts found that course content better reflected the current work of principals.

2. Improved leadership development practices in the district. Districts gained insight from the university collaborations. They used what they learned to strengthen their in-house professional development for principals.

3. A data system to identify, develop, and track school leaders. Districts created databases with information about current and aspiring principals to aid in decision-making. Data included individual skills, measures of student achievement, and evaluation results. Districts used the data to help select and place school leaders. They found the data especially useful in identifying weak areas to strengthen through principal professional development. Universities also found the data about graduates useful. They used it to inform their own program improvements.

The Role of Districts

Districts were actively engaged in the partnership. The report describes roles and contributions in detail. They include:

- Participating in steering committees and working groups

- Identifying and recruiting aspiring principals as program candidates

- Promoting engaging pedagogy. This included role-plays and case studies in place of lectures.

- District administrators serving as adjunct professors

- Working with universities to strengthen clinical experiences for aspiring principals

- Taking the lead on creating a data system to track school leaders.

Navigating Challenges

Districts needed to manage a number of challenges.

- The initiative was time consuming and complex. One useful strategy was for site teams to be led by someone with strategic perspective (such as a superintendent) and someone with the operational capacity to do the work.

- Regular meetings between partners maintained communication and engagement.

- Teams developed strategies to manage turnover in their membership. These included cross-training team members in different roles.

This brief also outlines considerations for other school districts interested in forming similar partnerships. These include:

- Finding the right university partner. That means a program that has a real desire to listen and respond to feedback.

- Considering their own system’s readiness to engage in the partnership

- Committing to refining the district’s role in the leadership pipeline.

Key Takeaways

- The Wallace Foundation launched an initiative in 2016 to improve university-based principal preparation. Seven universities in seven states participated in the University Principal Preparation Initiative. Universities worked with districts, states, and others to develop programming that reflected evidence-based practices.

- District leaders participating in the initiative reported three major benefits:

- Principal preparation became more closely linked with district needs.

- Districts improved their own professional development for principals because of what they had learned through the work with the universities.

- Districts developed databases with information about aspiring and sitting principals to aid in decision making.

- Districts were actively engaged in the partnership. They participated in the steering committee and working groups. They helped recruit and select program candidates. They worked with universities to strengthen clinical experiences for aspiring principals.

- Districts took the lead on designing a database to track aspiring and sitting principals.

- The brief describes how districts navigated a number of challenges. These included:

- Time constraints and keeping communications going. District and university schedules were not in sync, for example. Online meetings or combined online and in-person meetings were one remedy.

- Turnover of those helping lead the initiative. Redundant staffing, cross-training team members in different roles and tasks, and clearly documenting timelines and other matters helped.

Visualizations