When Henrico County Public Schools and Virginia State University began their partnership six years ago, their goal was to improve the university’s principal preparation program. Here’s what wasn’t on the horizon: redesigning the district’s leadership professional development.

But what began as a Wallace-sponsored initiative to ensure that university training of future principals reflected research-based practices, ended up sparking a big rethink of leader prep within Henrico itself. The result? Changes to and expansion of professional development across the spectrum from teacher-leaders all the way up to principal supervisors.

“This was an opportunity for us to develop a new partnership, to strengthen our principal pipeline and to be involved in the work of the principal preparation program,” says Tracie Weston, director of professional development at Henrico County Public Schools, which serves about 50,000 students in suburban Richmond.

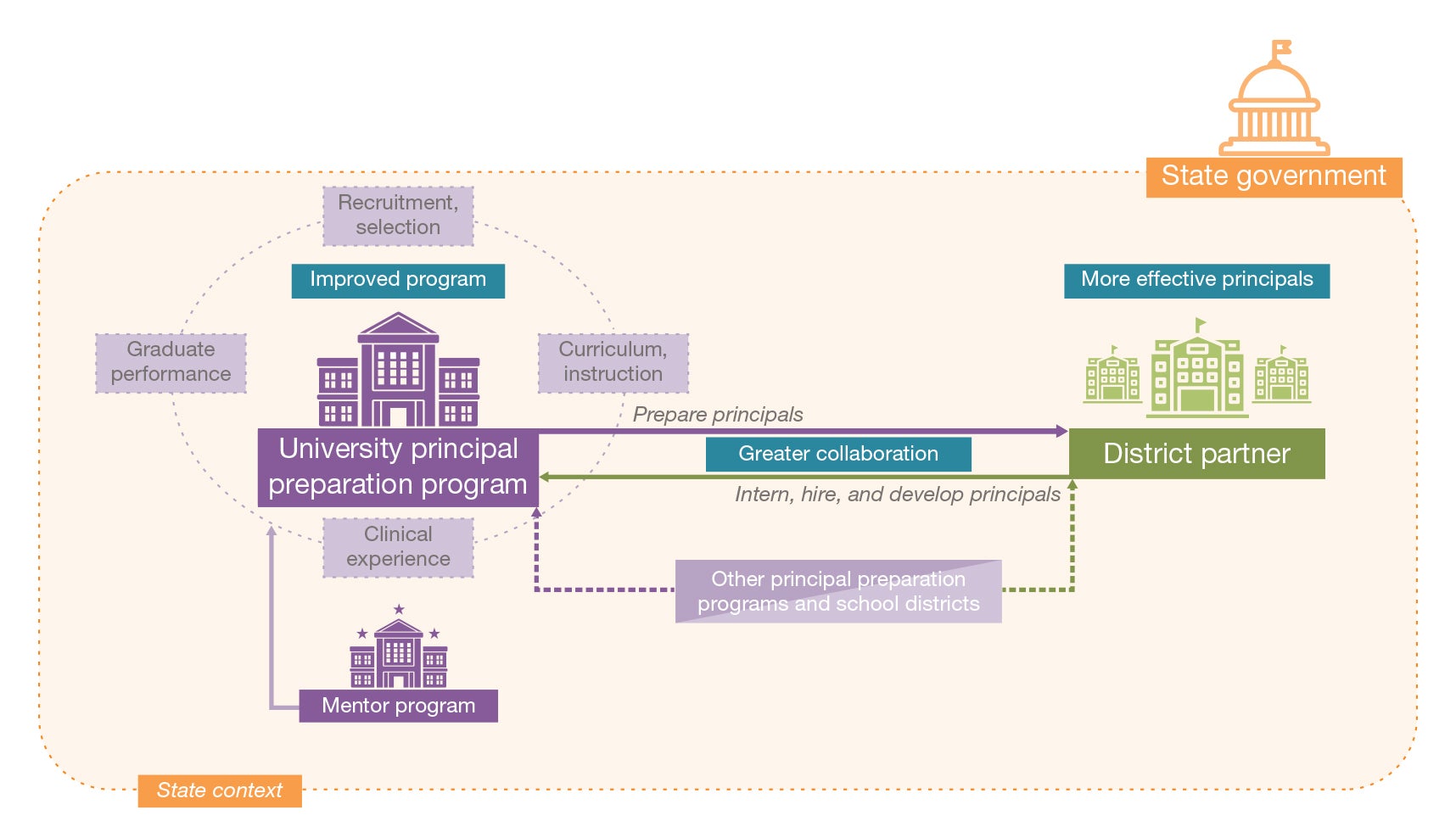

The “opportunity” in question was the University Principal Preparation Initiative (UPPI), in which seven universities in seven states each worked with a handful of local school districts and others to reshape their school-leader training programming to incorporate what research has found about everything from curriculum and clinical experiences to candidate admissions. Virginia State was one of those universities, and Henrico County was one of its partner districts, working, like all the other initiative districts, to ensure that the university programs responded to the needs and circumstances of the locales that hired program graduates.

An unexpected outcome, however, was that working to boost the university programming inspired the district to boost its own development efforts, according to a study by the RAND Corp. The initiative “raised the visibility of school leadership in the district and created a window of opportunity where district leadership supported PD,” RAND reported, using the initials for “professional development.” A number of changes resulted. For example, some of the topics addressed in the refashioned district PD, including leadership dispositions and equity, reflected priorities that Virginia State and its partner districts had discussed in redesigning the university program, according to RAND’s in-depth examination of the initiative. And Henrico’s PD for sitting principals began pairings of district leaders with sitting principals to emphasize policy and practice–an approach used in the university program.

Henrico County works successfully with a number of pre-service preparation programs, Weston says. As a district with a highly diverse student population, the school system welcomed collaborating as well with Virginia State, a historically Black university with a strong commitment to educational equity. “Much of our work in the college of education has been to bring about greater equity in the face of teacher education, counselor education and K-12 administration,” said Willis Walter, the university’s dean of education. “We have a fairly simple conceptual framework that is deeply rooted in culturally responsive pedagogy, and I think that is, for the most part, what attracted Henrico to some of the concepts we were teaching. We come at education from the standpoint of everyone has strengths.”

When it started working with the university, the district had several different programs that looked at pieces of leadership, but not leadership as a whole.

“To strengthen the things Henrico was already doing well, we wanted to make sure they had the right people at the table and the most vetted and best practices that were out there. And the best way of doing that was us working together,” Walter said.

The school system and university representatives bonded quickly, according to Walter. “I think that's because there was a common passion and a common focus,” he said. “We had some real knock-down, dragged-out conversations, but because everyone in the room trusted and appreciated the point of view that the other was coming from, it was never taken to an extreme.”

At the start of the initiative, Henrico had a small team responsible for providing professional learning for school leaders. Because these team members had all been principals, they recognized the need for ongoing, job-embedded professional learning for all leaders, including teachers. Throughout the UPPI partnership, Weston recalls, there were conversations about additional areas that needed to be included in a principal preparation program to ensure that leaders understood the responsibilities of the position, and that they were prepared for those responsibilities. These conversations led to taking a closer look at what professional learning the partner districts themselves were providing for school leaders.

The “moment of magic” as Weston calls it–the moment that led to the district wanting to revamp its entire professional development process–occurred when Henrico visited Gwinnett County, Ga., whose school district, known for its leader-development endeavors, worked with Virginia State in the UPPI.

Within the first six months of seeing the work in Gwinnett (a participant in an earlier Wallace venture), Henrico had developed its Aspiring Leader Academy, a district program designed to help prepare those aspiring to leadership jobs for their future administrative positions. Henrico’s goal was to create a program that was “meaningful, relevant and sustainable,” according to Weston. The interest in that academy was so high that Henrico expanded and introduced some new features to it.

“In year two, not only were we looking to identify our next school leaders, but we also wanted to provide professional learning for teachers who wanted to lead from the classroom–those who wanted to stay but grow,” said Weston. So, Henrico introduced a track for teacher-leaders. Both aspiring principal and teacher-leader tracks were aligned with national model standards for school leadership, the Professional Standards for Educational Leaders, and, while in training, the two groups came together for the morning sessions, which were led by the school system’s top administrative leaders–superintendents and directors–so that the candidates had the opportunity to “learn through the broader lens vision of how we work together to maximize student achievement.”

The afternoon sessions were tailored to the two different tracks, with the aspiring principals in one room and aspiring teacher-leaders in another.

District leaders also identified a gap in Henrico’s professional learning effort: development for assistant principals. They created a third track based on the teacher-leader effort, called the Assistant Principal Learning Series. In this track, candidates participate in “action research,” where assistant principals look at a problem of practice at their school. In their second year of the program, they can tap into more personalized options–at present more than 17 to choose from.

“So in the year we kicked off the AP learning series, every leader in Henrico County was getting a minimum of one day of professional learning targeted to an area of leadership where they felt they needed growth,” Weston said.

After adding APs, Henrico expanded the program yet again to include principal supervisors. That means that today the district has professional learning opportunities for aspiring leaders to assistant principals and principals all the way up to supervisors.

There may be more to come. “We're so excited about the work that we were exposed to and the connections we made, that we want to create a statewide cohort of principal supervisors so that principal supervisors across the state are receiving quality, relevant, practical professional learning for their positions,” Weston said.

Weston and Walter credit the partnership between the university and district for improving principal development on both sides.

“We were looking at best practice from a theory standpoint, and they were looking at best practice from an application standpoint,” Walter said. “I think the merging of those two benefited both of us. We were able to bring more relevant examples to our candidates that were about to graduate as well as to make sure that our faculty were on the right page when it came to the conversations they were having with prospective administrators in many of our surrounding communities.”

Although the grant from the University Principal Preparation Initiative has ended, Henrico and VSU have continued their strong partnership.

“It's an ongoing partnership where we lift one another, we share resources, we share experiences,” Weston said. “We're helping Virginia State see what the boots-on-the-ground challenges are, and how that can be reflected in the coursework that the students are being exposed to so that when they graduate, they are ready for the real-life challenges of K-12.”

Both Weston and Walter have advice for other districts and universities that wish to take on similar partnerships to revamp the way they develop and support school leaders.

“We always focused on the K-12 student, not on the personality, not on the administration,” Walter said. “It was all about what is best for the K-12 students in that community.”

Weston emphasized the importance of being willing to lean on partners for support. “Have conversations, reach out, make connections,” she said. “Because we learn from one another.”