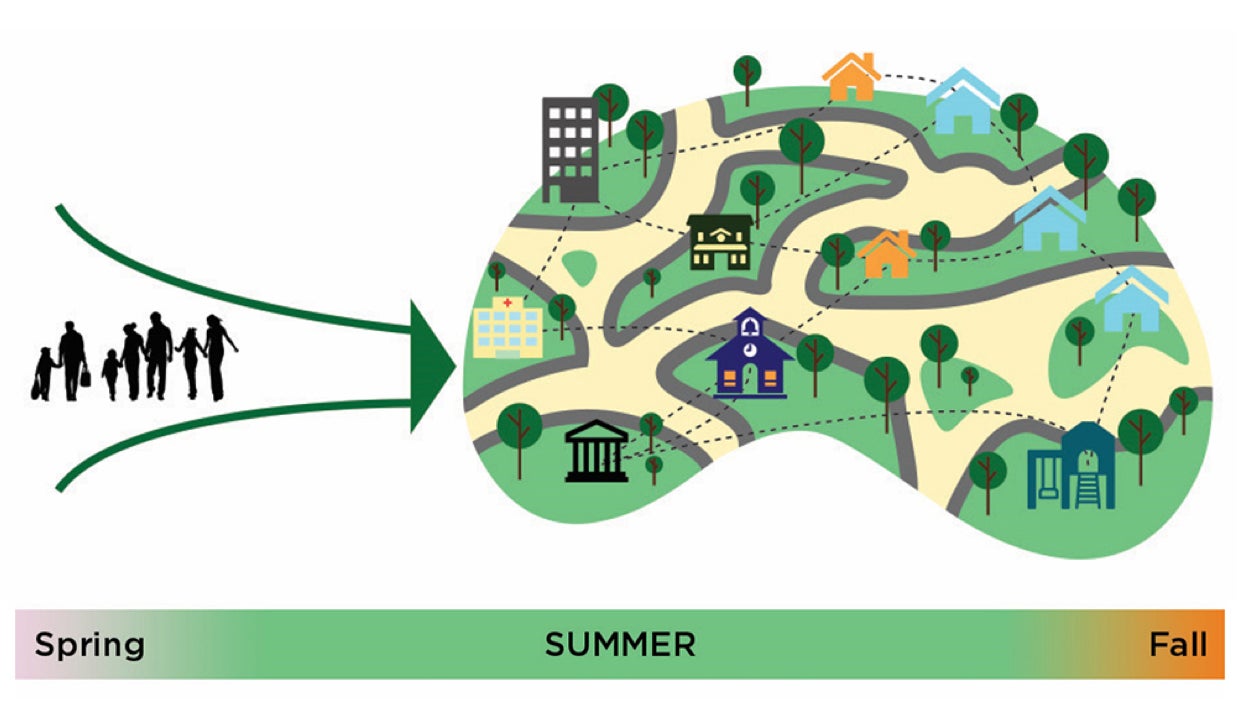

The phrase, “It takes a village to raise a child” has become commonplace in our society. Ask a researcher, though, and she might put a twist on the adage, saying, “It takes a system to raise a child.” In other words, children and young people are either helped or held back by the social, economic and physical conditions in which they live, and those conditions depend on an interconnected array of institutions, including schools, parks, public transit, the police and the courts, not to mention the family. Take summer learning: There may be an enriching summer program in your community, but if there’s no public transportation that goes there, the streets aren’t safe for your children to walk alone, and you work two jobs and can’t take time off to accompany them, then as far as your family is concerned, it may as well not be there at all.

Showing how different parts of the system influence the way children and young people experience summertime is just one of the achievements of a landmark report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Shaping Summertime Experiences—funded by Wallace and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and authored by the Academies’ Committee on Summertime Experiences and Child and Adolescent Education, Health and Safety—examines the state of the evidence on summer and children in America, with a focus on the availability, accessibility, equity and effectiveness of summer learning experiences. The report, released this fall, also shines a light on the experiences of groups that are often left out of the conversation about summer learning, including LGBTQ youth, those living in rural areas and those involved in the juvenile justice system.

We talked to one of the report’s authors, Jennifer Sloan McCombs of the RAND Corporation, about how the publication came together and what it has to say to those who play a part in shaping the system.

We talked to one of the report’s authors, Jennifer Sloan McCombs of the RAND Corporation, about how the publication came together and what it has to say to those who play a part in shaping the system.

What is the unique contribution of this report to the discourse on summer learning?

The report investigates the effect that summer has on school-aged children and youth across four domains of well-being: academic learning, social and emotional development, physical and mental health, and safety. We approached this charge from a “systems perspective,” examining the way people associated with various sectors—including education, city government, public safety, summer camp and families—contribute to the risks and rewards of summertime for children and youth. The recommendations are targeted to policymakers at the city, state and federal level, but we believe the report can be useful to practitioners, nongovernmental funders and scholars, too.

What was the process of putting the report together? What types of information did the committee consider? What types of people and organizations did it seek out?

The National Academies of Sciences formed a multidisciplinary committee with expertise that included pediatric medicine, youth development, summer and out-of-school programming, safety and justice, city systems building, and private employment. It was an amazing group of dedicated scholars and practitioners. I learned a lot from each of them. We met periodically over a year to discuss issues, listen to invited experts in public information sessions and develop recommendations. We specifically sought out data that would address the key aspects of our charge: the effects of summer on the developmental trajectories of young people, access to summer programs and the effectiveness of summer programs. Where we lacked data or needed additional context to help our understanding, we reached out to individuals and organizations who could help fill those gaps. For instance, during public information-gathering sessions, we heard from those with expertise in rural programs and policies, American Indian programs, and private employer interests and activities related to summer programs.

While members of the committee drafted the report chapters, the committee chair and NAS staff did a significant amount of work in the final production of the report, including editing, summarizing, fleshing out recommendations and weaving the report together.

One of the focuses of the report is inequity in access to summer learning and in outcomes for a variety of groups—not just black and Latino students and those from low-income families but also Native Americans, LGBTQ students, students living in rural areas, differently abled students, among others. How can providers, policymakers and funders begin to think about issues of equity pertaining to summer learning?

Based on the evidence, three things were clear to the committee: 1) Summer is a time of risks and opportunities for children and youth; however, those risks and opportunities are not equitably spread across populations. Children and youth who are less advantaged face greater risks in terms of safety, health, and nutrition and have reduced access to quality summer experiences. 2) To be effective, programs need to be aligned to community context and needs. 3) Certain populations of children and youth appear to be underserved and are definitely understudied, such as those who are American Indian, LGBTQ, migrant and refugee, or involved in the juvenile justice system.

To create more equitable experiences during the summer, we recommend that local governments conduct a needs assessment—one that gathers input from families and youth—in order to fully understand what the community needs and what barriers stand in the way. They should also do a systematic inventory of the programming available in the community and compare it to the needs assessment so they can identify gaps that need to be filled and priorities for public and private funding.

Individual program directors can also take action by looking at the population of children and youth they currently serve, identifying and addressing barriers to participation that certain groups may face, and engaging families and youth in the development of program content to ensure that it meets their needs and builds on their cultural strengths, including language, life experiences and culturally specific skills and values.

How do basic needs like safety and adequate nutrition affect the way children and young people experience summertime? What is the role of summer learning programs in addressing these needs?

Safety and nutrition are basic developmental needs that must be met year-round to ensure the health and cognitive development of children and youth. Unfortunately, during the summer months, children and youth from low-income families are more likely to experience food insecurity and lack appropriate supervision. Organized summer programs can help address these basic needs and more by providing meals and engaging activities overseen by trained and caring adults.

One of the report's conclusions is that families and communities have existing resources that can be used to provide young people with positive summer experiences. What are some examples of these resources, and how can those involved in creating, running and funding summer learning programs work with families and communities to make positive summer experiences more available and accessible?

The report describes how family structure, parental education and employment, the built environment, public safety and contact with law enforcement dynamically influence the summertime experience for children and youth. While children and youth from disadvantaged families and neighborhoods face greater challenges and risks during the summer, their families and communities also have a set of assets that can be leveraged. For instance, families are in the best position to identify the needs of their children and youth, the community context that has to be addressed to make positive summer experiences more available and accessible, and how community culture can be embedded into programming to make it more relevant to participants.

Visit our Resources page to find more research on summer learning, along with downloadable, evidence-based tools to help create effective summer programs.