This post is part of a series profiling the University of Connecticut’s efforts to strengthen its principal training program. The university is one of seven institutions participating in Wallace’s University Principal Preparation Initiative, which seeks to help improve training of future principals so they are better prepared to ensure quality instruction and schools. A research effort to determine the effects of the work is underway. While we await its results, this series describes how one university has fared so far.

In this post, associate professor Dr. Sarah Woulfin describes efforts to redesign the school’s curriculum. Other posts include descriptions of efforts to redesign internships, students’ and faculty members’ views about the new design and the ways in which the university works with community partners to ensure it is meeting their needs.

These posts were planned and researched before the novel coronavirus pandemic spread in the United States. The work they describe predates the pandemic and may change as a result of it. The University of Connecticut is working to determine the effects of the pandemic on its work and how it will respond to them.

These posts were planned and researched before the novel coronavirus pandemic spread in the United States. The work they describe predates the pandemic and may change as a result of it. The University of Connecticut is working to determine the effects of the pandemic on its work and how it will respond to them.

The University of Connecticut’s Administrator Preparation Program (UCAPP) aims to be a leading leadership program—with a curriculum that guides its students through rigorous, relevant learning experiences so they are prepared to serve as leaders and champions of equity on their first day on the job.

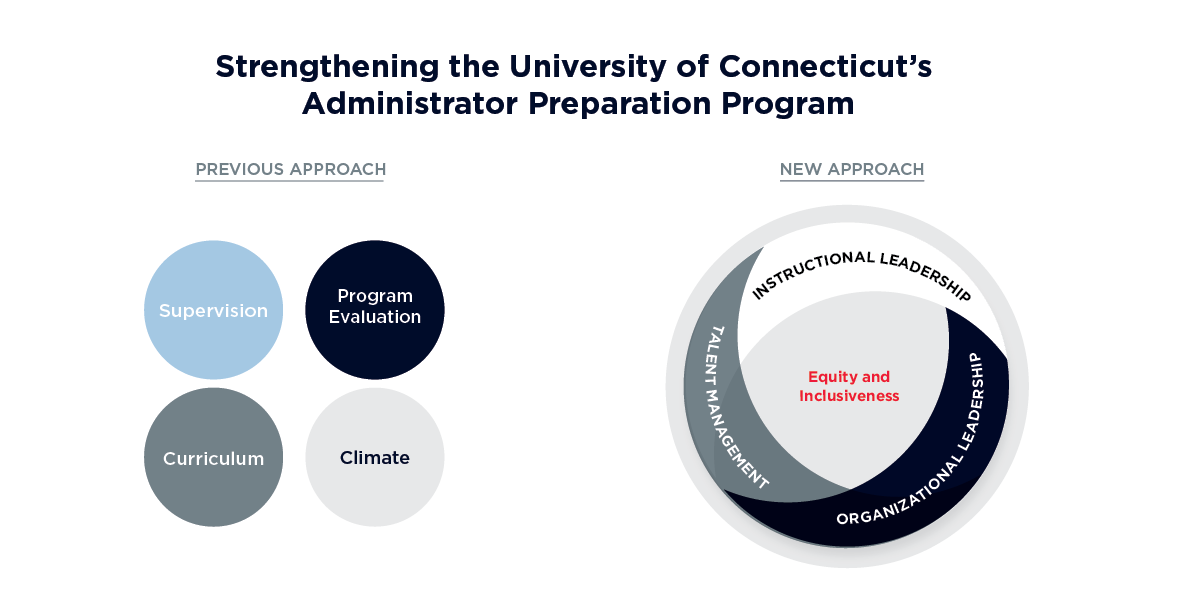

By 2016, however, we realized that our curriculum seemed too disjointed and static to reach this goal. It asked aspiring leaders to take a set of courses, one per semester, on supervision, curriculum, data-based decision making, and other topics. There were few bridges among these classes; When they completed one course, they were ‘done’ with the topics and content from that class.

We realized, as educators, that adults learn best when there are multiple opportunities to develop understandings over time and to question and expand frameworks and strategies, particularly those related to leadership. We wanted our principal preparation curriculum to reflect those tenets. So, a team of UConn faculty and local educators deployed structures, ideas, and routines to make sense of the existing curriculum and determine how to redesign it to attain our goals. Our process and the final product reflect tenets of adult learning and organizational change. We characterize this as principled improvements to principal-prep curriculum.

We focused our efforts on the potential growth areas uncovered by the Quality Measures self-assessment, a tool to help identify strengths and weaknesses of principal preparation programs. Three elements we could strengthen, the assessment found, were data tracking, internships and curriculum. We started with the curriculum so we could align internships and assessments to it.

We began by forming a team to analyze the existing curriculum, reflect on gaps and areas for improvement, set priorities, and design new structures and content for the program. In addition to our program faculty, the team included:

- Leaders from three area school districts that partnered with us in the Wallace initiative: the Hartford School District, the Meriden School District and the New Haven School District;

- Dr. Shelby Cosner from University of Illinois at Chicago, who coached us through the redesign process;

- Dr. Richard Gonzales, UCAPP’s director of instructional leadership, who led the work for the Wallace initiative;

- Joanne Manginelli, who coordinated the initiative work;

- Jonathan Carter, a UConn Ph.D. student and a graduate assistant for the initiative; and

- Two leaders from other nearby school districts: Erin Murray, assistant superintendent for teaching and learning at Simsbury Public Schools, and Erin McGurk, assistant superintendent for curriculum and instruction at Berlin Public Schools. We recruited Murray and McGurk because they both have experience in Connecticut schools and have teaching experience as faculty members in our program.

Their perspectives of practitioners helped us design rigorous, research-aligned coursework for future leaders. The perspectives of former UConn faculty helped formulate a curriculum that all instructors could draw on and effectively teach.

We developed routines and norms to enable our work and ensure we used time productively and documented steps of our process and decisions. For instance, our routines included time to brainstorm ideas and protocols to share feedback on documents. Our norms included short, frequent meetings and listening to all participants’ ideas and reflections.

The team began the process with an in-depth analysis of the existing program. This included systematic analyses of course syllabi, including the ways in which they cover National Educational Leadership Preparation (NELP) standards, and interviews with instructors and students to determine the extent to which our coursework addressed different pillars of leadership.

We reviewed evidence from this analysis as a team, discussed issues together, and reflected on the benefits and limitations of particular approaches to leadership development. During our discussions, we occasionally paused to ask the “magic wand” question: if you had a magic wand, how would you teach a certain aspect of leadership in the program? We took extensive notes so we could incorporate points into new curricular materials. We also reached beyond our team and brought in several faculty members and district leaders as advisors. For instance, Dr. Erica Fernandez, a former assistant professor of educational leadership at UConn, provided important insights to restructure the content and pedagogy related to parent engagement.

Our two years of work together were not without their challenges. First, we encountered some difficulties in developing new curricular structures, as opposed to layering new ideas atop previous syllabi. Some texts and assignments had become institutionalized features of the program, and the group had trouble deciding to delete them to create space for new materials. For instance, we had several conversations about whether to retain a text related to high-quality curriculum. Some wanted to keep it. But, after reviewing the Professional Standards for Educational Leaders and seeing how they address the leader’s role in implementing (rather than merely designing or selecting) curriculum, we decided it would take away from other, more crucial objectives. We note that removing items or foci is essential to prevent the curriculum from becoming too complicated for aspiring leaders and instructors to comprehend.

Second, we encountered obstacles in using evidence to ground decision-making. We had limited data on graduates’ successes and challenges. Therefore, we turned to literature to identify aspects of the principalship that new school leaders find challenging. We also asked state and district leaders about areas where new principals struggle. They pointed to strands such as implementation of special education services and communication with parents. As a result, we bolstered curriculum and instruction in those areas.

A major change in our approach was to shift from discrete courses on supervision, curriculum, data-based leadership, and principals as administrators to mini-courses on instructional leadership, organizational leadership, and talent management. The change allowed us to design coursework that weaves together ideas and information on what quality principals do to lead effective, equitable schools. We also embedded readings, activities, and assignments into all three courses that explicitly relate to issues of equity, race, and inclusion. For example, the instructional leadership course includes readings and learning activities related to how principals create excellent conditions and promote quality teaching to benefit English learners. Finally, we drafted outlines for each new syllabus that lay out two to three learning objectives for each class session and major NELP standards it should help aspiring leaders meet. In this manner, we transitioned towards standards-based class sessions, as opposed to merely addressing wider sets of standards during an entire semester.

To balance theory and practice, we carefully selected readings ranging from original research articles and policy documents, such as state guidelines on educator evaluation, to conceptual pieces such as Heath and Heath’s Switch that lay out key theories of organizations and schools. Our spiraled curriculum and intentionally sequenced class sessions and readings permit aspiring leaders to develop an understanding of theories and research on a topic, gain experiences to see the daily realities, and then return to the topic to braid together theory and practice.

We also designed clinical experiences to match specific portions of the curriculum. For instance, during the instructional leadership course, we ask aspiring leaders to observe a professional development session related to instructional improvement and then analyze how it reflects concepts they study in class. Similarly, during the talent management module at the end of students’ first year in the program, they conduct a practice observation cycle with a colleague.

We started teaching the new curriculum in the summer of 2019. With the support of the program’s director, instructors are making sense of the new curricular frameworks, syllabi, and assignments, and aspiring leaders are engaging in rigorous, relevant learning activities related to instructional leadership, organizational leadership, and talent management. We are studying the effort, collecting feedback and gathering ideas on how we can further refine the curriculum so it serves the needs of instructors and students. Ultimately, we hope it can ensure that we reach our target of preparing school leaders who can begin improving teaching and learning on day one.

STORIES FROM UCONN PRINCIPAL PREP PROGRAM