See how this nomadic arts organization is working to build a loyal, youthful following without a dedicated space of its own. A key new strategy is CRASHfest, a vibrant, annual evening of international music, food and dance, that the organization hopes will accomplish two, interconnected goals: increase name recognition and draw the younger audiences the organization needs to ensure financial sustainability. The company is also planning a massive re-branding effort.

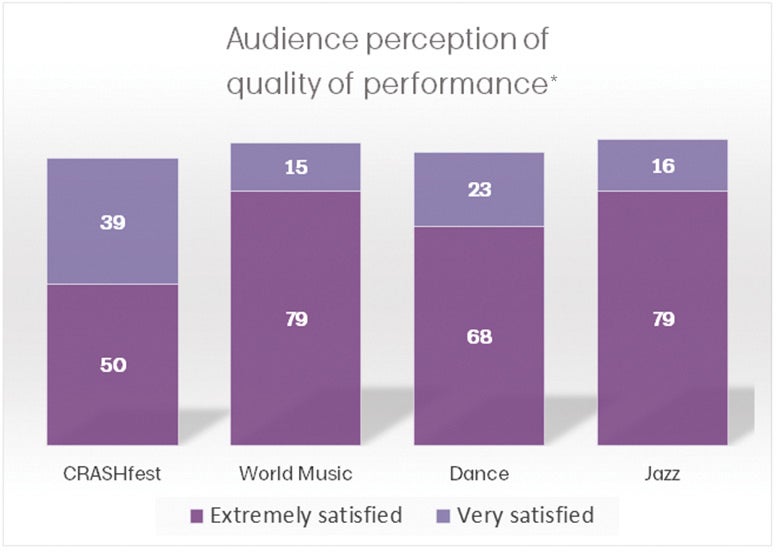

Jonathan Haase and Melissa Franco, both students at Northeastern University, stepped out of Boston’s House of Blues late on a brisk Saturday night in February 2018. They were wrapping up a packed evening at CRASHfest, an annual global music festival then in its third year. Since 6 p.m., three performance halls in the labyrinthine venue had hosted 15 acts, 10 local food vendors and nearly 2,000 fans representing dozens of cultures from around the world.

Haase, a fan of Gnawa spiritual music of Africa, had stumbled upon the event online. “I found out about this place when I saw Innov Gnawa on Spotify,” Haase said, referring to a New York City–based septet from Morocco who had finished performing moments earlier. “I heard there was someone playing Gnawa here and I wanted to hear it.”

He brought Franco along, who, like him, was new to CRASHfest. “I haven’t been to one before,” she said, “but I would probably come again because I like the fusion of all the cultures.”

Neither was aware of World Music/CRASHarts, the 28 year-old, eight-person nonprofit that has hosted the annual festival since 2016. But their path to CRASHfest could represent a solution to two intertwined, possibly existential problems for the organization.

The organization’s first concern is one that is baffling nonprofit performing arts organizations around the country: Older audience members are aging out of regular attendance and young people are not turning up often enough to take their place. World Music/CRASHarts’s audiences have aged with the organization, says founder and executive director Maure Aronson. “Our audience 28 years ago looked like me,” he said. “Our audience today, we found, still looks like me.”

The second concern is specific to many presenting arts organizations such as World Music/CRASHarts. The organization hosts dozens of world music, dance and jazz performances every year but has no space of its own. This nomadic nature gives it flexibility to find the right space for each of its performances, but, Aronson says, it comes with a downside. “What it takes away is brand identity,” he says. “If we do a concert at the Berklee Performance Center, a lot of people think, ‘Oh, it’s Berklee College of Music that’s doing the concert.’’’ Indeed, a 2015 survey of Bostonians showed that just 11 percent of area residents were aware of World Music/CRASHarts, even though the organization has been active for nearly three decades.

“The focus of the audience isn’t on the presenter, it’s on the artist,” says Mario Garcia Durham, president and CEO of the Association of Performing Arts Professionals, a service and advocacy organization for presenting organizations. “If you’re changing venues all the time, it becomes an additional challenge to make sure the audience knows that the performance is being presented by your organization.”

World Music/CRASHarts established CRASHfest in 2016 to help overcome these hurdles. Aronson and his team guessed that a festival would attract younger audiences by offering the sort of vibrant, social atmosphere they appear to appreciate. It could also increase the diversity of the organization’s audience by showcasing many different types of performances in one place. At the same time, it would allow the organization to plaster its name throughout the venue, raise awareness of its role in the event and advertise the wide variety of shows it offers throughout the year.

It was a sizable effort, especially for a small organization with a busy performance schedule. To make sure it got CRASHfest right, World Music/CRASHarts followed a careful process of exploration, experimentation, evaluation and refinement to improve results. In doing so, it also discovered insights that are fundamentally changing the ways the organization thinks about itself and presents itself to others.

Finding out what audiences want

World Music/CRASHarts’s work started with a three-month, $75,000 Wallace-funded effort to study the preferences and behaviors of both current audiences and the 21- to 40-year-old prospects that the organization hopes to attract. It recruited market-research consultants to help determine whether a festival would draw its target audience, understand the factors that drew or dissuaded this audience and how World Music/CRASHarts could keep the audience engaged throughout its season.

Beginning in July 2015, seven months before the first CRASHfest, consultants e-mailed surveys to people who had purchased tickets to its shows and to a list of area residents whose names were purchased from Survey Sampling International, a digital research firm. It also worked with its consultants to conduct in-person focus groups of current and potential audience members.

The research confirmed many of the organization’s suspicions. Existing audiences are committed to World Music/CRASHarts, with the average patron attending three performances every two years. But they are also older than the average Boston resident at large. More than 40 percent of Boston is between 20 and 40 years old, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. But just a quarter of World Music/CRASHart’s audience falls in the 21-to-40 age range that the organization is targeting.

There was potential to change this picture, however. Sixty-four percent of those surveyed—including 61 percent of millennials and 57 percent of respondents who had never attended a World Music/CRASHarts event—liked the idea of World Music/CRASHarts when they heard about it. More than half acknowledged that they would at least consider going to a show.

A festival, moreover, appeared to be a good way to realize this potential. Seventy-five percent of respondents liked the idea of a winter festival that combined many types of performances with foods from around the world. It could also balance the preferences of millennials and Gen Xers, many of whom wanted opportunities to dance and socialize, with the preferences of baby boomers, who just wanted to sit back and enjoy the show. Additionally, it could balance the desire of those who wanted to see familiar acts with the desire of those who wanted to discover something new.

Research also informed the details of the festival. It pointed to a preference for a manageable number of acts, each performing long enough to give an audience a good sense of its repertoire. As a result, World Music/CRASHarts booked 10 bands for the first festival, each playing for about an hour. Three-quarters of millennials said familiarity with artists was among the most important factors determining their attendance. So World Music/CRASHarts made sure to book high-profile bands along with the lesser-known acts that may be popular with the organization’s existing audience members. Surveys pointed to a preference for a ticket price of about $40 for the evening, which is what World Music/CRASHarts charged for advance tickets. (Tickets at the door were $50.)

Research even helped pick the venue for the event. Aronson’s original idea was to set up a main tent in Harvard Square, the historic plaza in Cambridge, Mass., with accompanying performances and activities in venues nearby. Surveys and focus groups, however, pointed to a preference for multiple stages under one roof. A respondent at one focus group specifically recommended the House of Blues, which proved to be a viable venue for the event.

First attempt; mixed but encouraging results

The first CRASHfest took place at the House of Blues on January 24, 2016. Kishi Bashi, a Japanese- American multi-instrumentalist performer who broke into the indie rock scene four years earlier, headlined the event. Also included were Angélique Kidjo, a Grammy Award–winning Beninese singer-songwriter, and lesser-known acts such as The Dhol Foundation, a London-based Punjabi percussion group, Afro-Colombian ensemble Monsieur Periné, and American classical and folk musician Leyla McCalla, among others.

World Music/CRASHarts staffers transformed the House of Blues. They covered the space with signage and multi-ethnic decorations not only to create a festive multicultural atmosphere but also to ensure everyone knew who organized the event. “They see it transformed entirely,” says associate director of development Alexandria Petteruti of audience reaction to the House of Blues during CRASHfest. “It’s a new space with a lot of different elements that we very carefully choose to give a World Music/CRASHarts vibe.” Concert-related swag such as earplugs and lip balm was emblazoned with the CRASHfest logo and World Music/CRASHarts’s web address. Advertisements for upcoming performances, including those the organization set up especially to draw younger audience members, ran in a cycle on giant TV screens throughout the venue.

Placing the organization’s signature on the event was just half the job, however. World Music/CRASHarts wanted to make sure audiences remembered the organization—and the shows it advertised—after they left the House of Blues. The team therefore added several promotions and activities designed to collect information so it could remind visitors of upcoming performances. Want some swag? Give a volunteer your age and contact information. Want your photo booth picture sent to you? Type in your e-mail address. Later in the season World Music/CRASHarts will use this information to target audience members—in particular for energetic standing-room-only club shows added specifically for younger prospects.

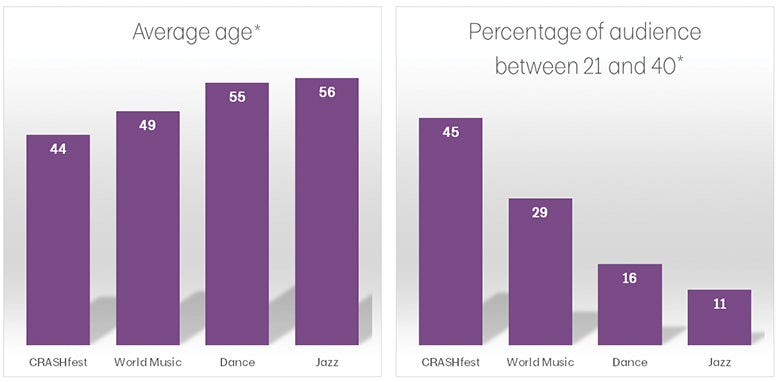

Results of the first CRASHfest were encouraging: 1,500 people attended, meeting the organization’s goal and grossing $38,000. Sixty-one percent of the audience was new to World Music/CRASHarts, 56 percent of whom were younger than 40. Half the total audience was in the target 21-to-40 age range, about twice as many as the average World Music/CRASHarts performance. The average visitor was 44, four years younger than the average patron at other world music performances and more than a decade younger than the average age at dance and jazz performances.

Reactions of these audiences appeared to be positive. In post-festival surveys, 89 percent of respondents said the event was excellent or very good, and 91 percent said they were likely to return the following year.

Still, there was room for improvement. Audiences found food choices to be limited, especially for vegetarians and the gluten-free. Many food stations ran out by 8 p.m., just two hours into the program. Many people had trouble getting to the smaller stages in the House of Blues, and several said that the schedule and set times were unclear.

Two data points appeared discouraging but were easily explained. First, just half the audience was “extremely satisfied” with CRASHfest, a much smaller percentage than the share of audiences that feels similarly about other World Music/CRASHarts performances. It stands to reason, however, that audience members would be more enthusiastic about a prominent performer they sought out than they would be about a large multistage festival with several unfamiliar acts.

Second, just 14 percent of younger CRASHfest attendees returned for other performances that season, well short of World Music/CRASHarts’s 25-percent target. But there were just three months of programming left in the season after CRASHfest, and staffers soon realized they had set a goal that was too lofty. The organization therefore revised its goal to draw 25 percent of CRASHfest audiences to main-season shows over the next two years. As of September 2018, the organization had come within one percentage point of this goal for 2016 CRASHfest attendees.

Lessons learned and applied

World Music/CRASHarts applied many of the lessons it learned from the first CRASHfest to streamline the event for the next two years. It added clearer signage to ensure audience members could find the performers they sought. It extended the hours for food stalls and, in the third year, invited local restaurants and food trucks to set up at the event. It offered wallet-size cards at the entrance with lists of performers, stages and set times so people wouldn’t miss shows they came to see. In 2018, it added a bump-out stage in front of the main stage to host lesser-known acts, reduce dead time while a main act swapped out its gear and ease pressure on smaller rooms.

These improvements and the buzz about the festival kept engaging new audiences, and numbers moved in the right direction. Attendance increased from 1,500 in 2016 to 1,850 in 2018. Proceeds from the festival increased by more than 60 percent, from $38,000 to $61,000. The share of the CRASHfest audience new to World Music/CRASHarts stayed steady—between 54 and 61 percent—even as crowds grew.

The festival’s ability to draw audiences to the rest of the World Music/CRASHarts’s season is yet to be determined. But the organization is seeing some CRASHfest attendees turn up at other performances, especially those offered specifically for younger people. “It’s a little too early to really see major trends,” says Petteruti, “but we do see reengagement with people who haven’t been to a concert before they attended CRASHfest.”

A deeper change: a new name to strengthen the brand

In CRASHfest, World Music/CRASHarts may be discovering a new, more engaging way to interact with its audiences. But the process of developing the festival produced a much more fundamental change in the organization: a new name and a whole new brand identity.

There was no research behind the name World Music/CRASHarts, according to Aronson. The organization was simply called “World Music” when Aronson founded it in 1991 to host diverse international artists. When it added contemporary dance and jazz to its repertoire in 2001, it introduced “CRASHarts” to inject an edgier flavor.

“CRASHarts is a name that I came up with,” Aronson says. “When we expanded into contemporary programming, I just thought, ‘Oh that’s a cool name,’ and just tagged it onto World Music.”

Nearly two decades later, focus groups revealed at least two major limitations of the name.

First, it is somewhat unruly. “It’s just too much to remember,” says associate director Susan Weiler. “We even asked people who were pretty familiar with the organization and they couldn’t repeat it back to us. They’d say it was ‘World Crash Arts’ or ‘Crash Arts World.’ It became pretty clear that we had a problem there.”

Second, the term “world music” no longer means what it did in the 1990s. Mark Minelli of Minelli, Inc., a branding and design firm that is helping World Music/CRASHarts rebrand itself, points to the shortcomings of the term in the Internet age. “What does that mean now that we have access to any kind of music anywhere?” he asks. “I can be in Mali but be really interested in the Beatles. It really changes the definition of what world music is.”

Attendees at the 2018 CRASHfest echoed a similar sentiment. “I don’t know what that means,” said one millennial when asked if he likes world music. “To me, it’s like asking if I like music.”

The theme became clear to World Music/CRASHarts early in the process of planning the first CRASHfest. “After the very first focus group,” says Aronson, “the moderator came up to me and said, ‘You need to change your name, yesterday.’”

A name change is no trivial task, however. A new name could compromise the relationship World Music/CRASHarts has built with its existing audiences. Some could conclude that an organization they knew of no longer exists. Others may suppose that the change in name signals a change in the quality of performance they had come to expect. But, says Weiler, market research gave the organization the confidence it needed to charge ahead.

“The research gave us the ammunition to say, ‘This is paramount. We can’t wait any longer,’” she says.

The organization is being more methodical about a new name than it was when Aronson first came up with World Music/CRASHarts. Again, the effort began with a deep look at audience data. “Understanding the data is absolutely critical if you’re doing a rebranding initiative,” says Minelli. “Otherwise you’re just flying blind.”

The data pointed to several goals a new name would need to address. It would have to demonstrate the focus of the organization and its level of expertise, taking perceptions of the organization “from all over the place,” as Minelli puts it, “to depth and diversity.” It would have to appeal to younger people. It would have to balance a clear description of the organization with an emotional resonance that would draw audiences in.

Most important, it would have to serve as a beacon for the organization. “You don’t want the brand to be the anchor trailing behind you,” says Minelli. “You want it to be the North Star in front of you, inspiring you where to go next.”

World Music/CRASHarts and Minelli, Inc., spent nearly a year poring over data, defining goals, conducting focus groups, collecting ideas from staff and board and narrowing them down to the most viable options. “It is not an easy process,” says Aronson. “From the new name to the graphics, to the look, to the messaging, to the board discussion about the new name. There’s nothing easy about it."

The organization settled on a new branding identity in August 2018, coming up with a new name that broadcasts a focus on international performing arts and a tagline that invokes the social and emotional benefits audiences could derive from them. For now, staffers are keeping mum about the new brand. The organization will reveal it methodically during its 2019–2020 season, first to existing supporters and then to the broader public.

It’s a significant change, one that the organization must implement with care. “Having a new name is really scary,” said Weiler. “We have 40,000 audience members who hopefully know a little bit about us. We don’t want to lose them.”

World Music/CRASHarts will have to commit to an intensive marketing effort to ensure both existing and potential audience members know the new name and the organization behind it. “That will be through anything from wrapping a bus to social media to [advertisements] on the subway,” said Aronson. “But the challenge for us now is we need to find a quarter-million dollars to do this.”

World Music/CRASHarts has invested an enormous amount of time and money in CRASHfest and the broader rebranding effort that is now accompanying it. Results appear to be moving in the right direction, but Aronson figures it will take years to determine whether the efforts worked.

“We need at least six years to understand what comes of CRASHfest,” he said. “We may need ten.”

Photos by Sarosh Syed and Eric Antoniou.

This article and video are part of a series describing the early work of some of the 25 performing arts organizations participating in The Wallace Foundation’s $52 million Building Audiences for Sustainability initiative. Launched in 2015 in response to concerns about a declining audience base for a number of major art forms, the endeavor seeks to help the organizations strengthen their audience-building efforts, see if this contributes to their financial sustainability, and develop insights from the work for the wider arts field.

Start a Discussion

The purpose of this Discussion Guide is to help arts administrators, board members and arts practitioners working within varying disciplines and with a range of budget sizes to better understand and apply lessons from another institution’s experience to their own context. The guide can serve as a teaching aid for small-group discussions, as well as individual study. It is designed to be used in conjunction with the written and/or video versions of the story.

Stories in Building Arts Audiences