For years now, downtown Seattle has thrummed with the sound of earth movers and cranes, as corporations like Amazon, Microsoft and Google moved into the area and even more new residential buildings went up. The noise could be unbearable. But to the Seattle Symphony (SSO), the rumble—and the influx of people it brought into the neighborhoods surrounding Benaroya Hall—sounded like opportunity knocking.

When Simon Woods became chief executive in May 2011, followed that fall by the arrival of Ludovic Morlot as music director, the Seattle Symphony’s audience was shrinking. During the 2011-12 season, its core Masterworks concerts were selling at just 63 percent of paid capacity—a low not seen for a dozen years or more. Something had to be done.

As SSO began to consider changes, officials kept its mission—to unleash the power of music, bring people together and lift human spirits—top of mind. Tacitly, that statement implied being a vital part of the city. And: “When you think about Seattle,” said Woods, “I think about two things more than anything else which make up the values of this city. One is about innovation and the other is about community.”

Guided by those two principles, the symphony set out to capitalize on downtown Seattle’s growth spurt. The staff believed that if they could identify and appeal to this population—which is growing twice as fast as Seattle’s overall populace—they could arrest the downward slide in sales and lure new, younger listeners to Benaroya Hall. “There was this population of people living downtown who [we thought] would love the opportunity to just be able to walk to the symphony,” said Charlie Wade, who joined SSO in March 2014 as Senior Vice President for Marketing and Business Operations.

To attract these potential listeners, SSO generally tried to play to their assumed musical inclinations. “We want to think about people’s preferences,” explained Woods. “We want to do the programming that brings in the largest audiences.” But, he added, “we’re also mission-driven.” That includes presenting music that provokes and challenges the audience.

Assumptions and Hypothesis

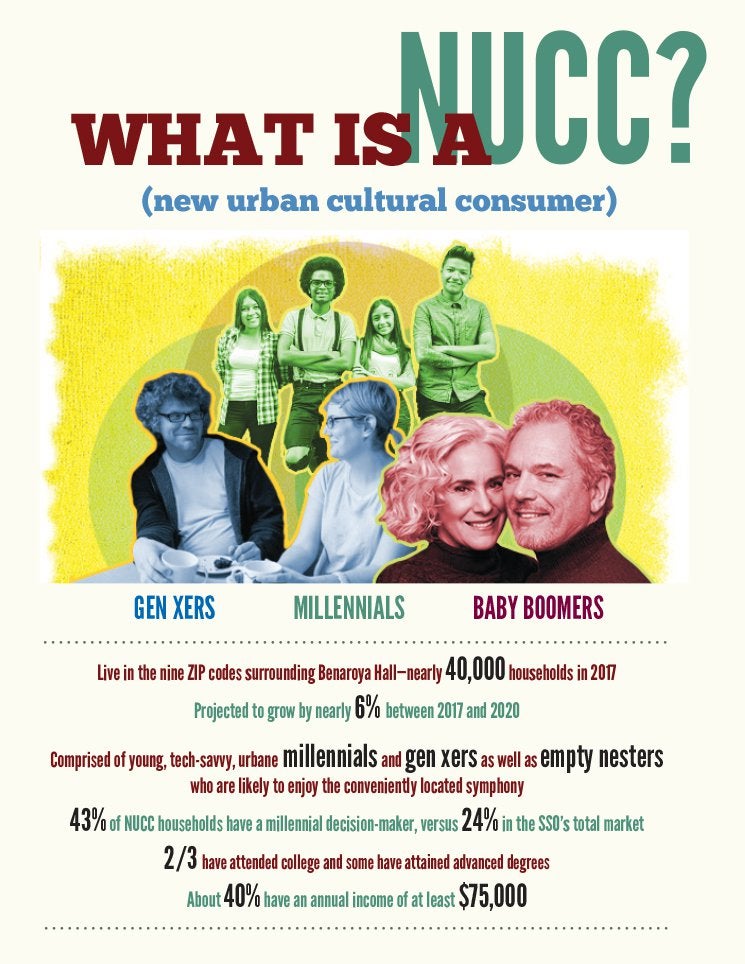

Other than where they lived or worked—in nine nearby ZIP codes—little was known about this prospective audience, which SSO later began to call “new urban cultural consumers,” or “NUCCs” (pronounced “nucks”). The symphony staff guessed that this group would be significant in number, tech savvy, urbane, experience oriented and eclectic in their musical tastes. They figured they would be young, mostly Millennials—though they could see that their neighbors included some Gen X-ers and baby-boomers, too.

Meanwhile, the symphony devised three concert formats, all less formal than Masterworks, all launched during the 2012-13 season, and all marketed under the “Listen Boldly” umbrella. While they were never intended to be a formal series or viewed as a stepping stone from one concept to the next, there was some initial thinking that they might spur general interest in the symphony and therefore potentially in the core Masterworks concerts.

One format, called “Sonic Evolution,” is an occasional, genre-bending concert that, in the words of Elena Dubinets, Vice President of Artistic Planning, “embraces the popular music legacy of Seattle.” It blends the orchestra’s classical prowess with the musical styles of local bands and sometimes incorporates video. For the inaugural concert, SSO played the first orchestral piece ever written by electro-acoustic “alt-classical” composer William Brittelle—Obituary Birthday (A Requiem for Kurt Cobain), the Nirvana founder who was a key member of the Seattle grunge scene. Since then, these concerts have featured performers from groups like Mad Season and Pearl Jam.

“Untitled,” the second new concept, is a 10 p.m. chamber music concert that presents challenging 20th- and 21st-century compositions in Benaroya Hall’s darkened lobby, whose capacity is about 500. With its intimacy, club-like atmosphere, sit-where-you-like character (choices include tables and cushions on the floor, as well as chairs) and dramatic lighting, Untitled was aimed at a youthful audience that would like edgy music. Scheduled three times per season, these concerts present work, for example, by modernist John Cage and by Trimpin, a sound sculptor/musician whose piece featured chimes and a preprogrammed piano.

“Untuxed” starts at 7 p.m., an hour earlier than Masterworks, lasts no more than 75 minutes and offers classical music drawn from SSO’s Masterworks series to busy people who might have avoided the longer, later, costlier core series. An early program featured works by Beethoven, Dvorak, Max Bruch and John Adams.

Even from the start, more seemed to ride on Untuxed, which is set in the main hall on Friday nights and offered five times per season. Assuming that these concerts would be an introduction to classical music for young attendees, SSO drafted bassist Jonathan Green to act as host, providing insight about the program. It also invited concert goers to mingle with the musicians, go backstage for a tour, or sit on stage. Breaking down another presumed barrier, SSO decreed casual clothes for its musicians, signaling that the audience could do likewise. At Untuxed concerts, blue denim is a lot more prevalent than black.

After a strong start in ticket sales for Untuxed, SSO began to harbor even more hope for it. Staff wondered if Untuxed could become an “on-ramp” to Masterworks—if the young newcomers, liking what they heard, would then buy tickets to the longer concerts. Describing SSO’s aspirations, Wade said: “We’ll provide our audience with this sort of introductory music that would then get them moving to our core series, and that would be great.”

Still, staff also recognized that Untuxed might also be an “off-ramp” from Masterworks: If many ticket buyers defected from the core program to the shorter, cheaper program, that would be a negative, revenue-depleting result.

Market Research

All of this was conjecture until SSO received a grant to conduct audience research. Following traditional protocols in market research, it began with focus groups, which could be counted on to provide qualitative perceptions. Those comments could then be used to draft questions for a quantitative study.

In July 2015, a contractor conducted several focus groups, each with seven to nine college-educated participants, male and female, ages 21 to 64. Two groups, the “musically inclined,” had purchased tickets to at least two different musical genres (classical, Latin, jazz, opera, blues, pop or rock) in the last year and were not averse to attending classical concerts. The other five groups were segmented by their attendance at one of the Masterworks, Untitled, Untuxed or Sonic Evolution performances.

During these sessions, each lasting about two hours, SSO administrators watched (unseen) as participants reviewed marketing materials and video excerpts of concerts, providing feedback on their habits, motivations and preferences. In the fall, SSO followed up with a survey circulated to patrons and non-patrons, receiving responses from a total of 2,084 people.

The results provided encouragement, confirming that NUCCs existed in sizeable numbers and were good prospects for the symphony: Some 83 percent professed an interest in the arts. SSO also learned that NUCCs included not only Millennials but also more Gen X-ers and older empty nesters, returning to the city from the suburbs, than originally suspected.

For all three concerts, the enticements the symphony had added, like backstage tours and an M.C., were often appreciated but not essential to success. It was the music itself that drove attendance.

In fact, Untuxed’s strong initial sales had tailed off for that reason. Audiences did not want to hear the pieces by, say, Bruch and Adams that were on that early program; they preferred music that they knew in advance that they would like. They appreciated works like Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, Copland’s Symphony No. 3 and Bernstein’s Candide Overture—nothing more adventurous.

“Untuxed is actually the most conservative audience that we have,” said Wade; they wanted music that they “know and love.”

In post-performance interviews at a 2017 concert, several people confirmed that. “Programming plays a big role in my selection of the Untuxed series,” said one audience member. “I love the fact that it is ‘the best of’.” Another, who found the music “relaxing,” agreed and voiced appreciation for Untuxed’s other key draw—its early start and short span. “I am going to be able to make it home for my kids’ bedtime, and that means a lot to me,” she said.

SSO was more accurate in programming the other new concerts. Untitled—the 10 p.m. concerts offering challenging modern music—attracted a somewhat older audience, on average, than expected, but no matter: In addition to appreciating the informal atmosphere and staging, they are die-hard music lovers who also attend other SSO concerts. “Those who come for Untitled are probably the most passionate about the symphony overall,” said Dubinets—a notion easily confirmed by after-concert interviews. Explaining why he attended, Mike Castor said, “It’s definitely the music—the really inventive programming. It’s awesome to see such experimental and modern music being put on display this way, and it’s equally awesome to see how many people come to see it and are very excited by it.”

For their part, the patrons of the genre-bending Sonic Evolution concerts appreciated the concerts’ connection to Seattle and the blend of musical genres—and said they would return.

Having found their audiences, Sonic Evolution and Untitled will continue as part of SSO’s programs, without the need for major tweaks or more research.

Untuxed was another story.

Course Corrections

The symphony had been programming Untuxed partly on what was easiest—which pieces were being rehearsed at particular moments, for example, and could slip into Untuxed without a fuss. “We were falling into a bit of the trap that a lot of organizations do,” said Wade. “You become more focused on what’s convenient for you internally versus what your audience actually wants.”

So while “Masterworks programming remained what it was, this healthy mix of traditional, progressive, interesting and new and familiar,” Wade said, Untuxed required a pivot. For it, SSO began “cherry-picking” only the most familiar and best-loved works by well-known composers from its repertoire.

Dubinets conceded that some musicians were initially hesitant about the changes, but said they accepted them because they were supported by research. “Musicians don’t enjoy seeing empty halls, so we had to make it work,” she said.

And it did: During the 2016-17 season, Wade reported, SSO saw a 40 percent increase in attendance for Untuxed, compared with the 2015-16 season.

Perhaps disappointingly, the research also indicated that Untuxed was not going to be an on-ramp for Masterworks. Analysis of SSO’s ticket purchase database shows that for the past four seasons (through February 2017), only about 1 percent of first-time Masterworks ticket buyers had first purchased Untuxed tickets. And among those patrons who attend both Untuxed and Masterworks concerts, most (55 percent to 65 percent, depending on the year), bought their Masterworks tickets first.

The upshot: Untuxed, like Sonic Evolution and Untitled, is a separate program—or brand extension—neither more nor less. But all three are valuable, even without affecting attendance at the core Masterworks concerts, because they draw new audiences to Benaroya Hall. They are providing, as Wade says, “another lens on the orchestra,” taking SSO deeper into the community.

There was good news in the market research, too. In the 2016-17 season, about 17 percent of Untuxed ticket buyers were first-time attendees, up from 9 percent in the 2015-16 season – which because the sample is small is not statistically significant but is directionally encouraging. And overall, first-time buyers of both Masterworks and Untuxed tickets are significantly younger than those who are experienced ticket buyers – for the last three seasons, their median age is 46 versus a median age of 59 for experienced buyers. That is evidence that SSO is on the right track in pursuing NUCCs.

The numbers suggested that SSO would benefit from marketing outreach to NUCCs. SSO’s penetration of this market has increased every year since 2014, with a cumulative total of about 12 percent over the whole period—about double its penetration in Seattle outside the NUCC ZIP codes. Still, for the last two years NUCCs made up only about 7 percent of the total symphony audience. There is plenty of room to grow.

Outreach and Relationships

To attract more NUCCs, SSO decided to pump up marketing, starting with more digital efforts. The symphony hired a Digital Marketing Manager in the summer of 2016, to create a larger online and social media presence, including more videos.

SSO also created the position of Corporate and Concierge Accounts Manager, held by Gerry Kunkel, to reach out to corporations, hotels, condominiums and apartments downtown. On a recent sales visit to the concierge of an apartment building, Kunkel’s pitch led with “the possibility of sharing the symphony with your homeowners and your tenants.” He explained the symphony’s varied programs, from Masterworks to Harry Potter movie nights, and said he could give tenants ticket discounts, generally 15 percent off the online price and sometimes a waiver of the 12 percent handling fee.

Since his hiring in April 2016, Kunkel has signed up about 70 companies, 30 residential buildings, and most downtown hotels, bringing in ticket sales of $177,000 from new patrons or those who’d not bought a ticket in more than a year.

But is the cost of this outreach worth it? Early evidence suggests yes. The investment in digital marketing led to $3.7 million in digital ticket sales in the 2016-17 season, much more than last year (though SSO does not have an exact number). Kunkel’s efforts have yielded sales that far exceed, by multiples, the cost of hiring him.

These marketing efforts reach beyond NUCCs, of course, and they are paying off overall. For the 2016-17 season, SSO sold 74 percent of Masterworks’ paid capacity, continuing an almost steady increase since the 2011-12 low.

To encourage newcomers to return, SSO now also focuses on improving the customer experience, increasing satisfaction and loyalty. It has scheduled sessions with a highly regarded hospitality industry consultant to train employees, from box office to parking attendants. In workshops, they learn to welcome guests warmly, with a smile, to anticipate their needs, to say “you’re welcome” and “certainly”—to reflect what Wade calls “the seriousness of culture and care for the audience”—rather than the more offhand “no problem” and “whatever.”

SSO has also created a “Surprise and Delight” program for new subscribers. In it, staff members greet them by name when they arrive at Benaroya Hall and tell them SSO is glad they’ve come. “What we found,” said Wade, “is that, in fact, the people that we greet renew at a significantly higher rate than people that we don’t greet.” In the 2016-17 season, that tally was 41 percent versus 29 percent.

At each concert, about 35 new members also hear a buzz when their ticket is scanned, and are told to go to the information desk. “They are looking curious,” Kunkel said—and about five to seven of the 35 never go to the desk, he added. Those who do, however, are thanked and given free drink tickets. “Their concern falls away,” said Kunkel, who works the desk, “and they get a big smile on their faces.”

SSO’s experience with building new audiences has helped foment change within the organization. Information, once held close by administrators, is shared with all departments. The programming process, once the sole purview of the music director’s office, is symphonywide.

“Now,” said Dubinets, “we have monthly season-planning meetings with representatives from all departments. We look at all sides of our activities. It’s not just programming. It’s not just what happens behind the scenes. It’s also what happens in the front of house and with donors and on social media. And we look at this whole package as we plan the seasons.”

For example, she continued, in planning of the 2018-19 season, the group realized that the Untuxed series did not contain enough “old chestnuts.” After much mulling, and solving a scheduling issue, the team moved Rachmaninoff’s enduringly popular Piano Concerto No. 2 from Masterworks to the Untuxed series and substituted a less-well-known piece in the Masterworks lineup.

SSO is also increasing its outreach efforts to its young neighbors, who the symphony now knows are ripe for cultivation. “Part of our strategy in the coming year is going to be, let’s bring quartets or let’s bring trios and let’s perform in one of the larger condominium buildings or at a corporate event,” Wade said.

That won’t be the end. “There’s a lot we don’t know about NUCCs,” Wade said. In new focus groups this fall, SSO plans to delve into how they buy tickets, how they might be approached to become members, what information they would like, and how they are best reached digitally. The answers will provide a better guide to the rapidly transforming future of the symphony—and the city.

This article and video are part of a series describing the early work of some of the 25 performing arts organizations participating in The Wallace Foundation’s $52 million Building Audiences for Sustainability initiative. Launched in 2015 in response to concerns about a declining audience base for a number of major art forms, the endeavor seeks to help the organizations strengthen their audience-building efforts, see if this contributes to their financial sustainability, and develop insights from the work for the wider arts field.

Start a Discussion

The purpose of this Discussion Guide is to help arts administrators, board members and arts practitioners working within varying disciplines and with a range of budget sizes to better understand and apply lessons from another institution’s experience to their own context. The guide can serve as a teaching aid for small-group discussions, as well as individual study. It is designed to be used in conjunction with the written and/or video versions of the story.

Stories in Building Arts Audiences