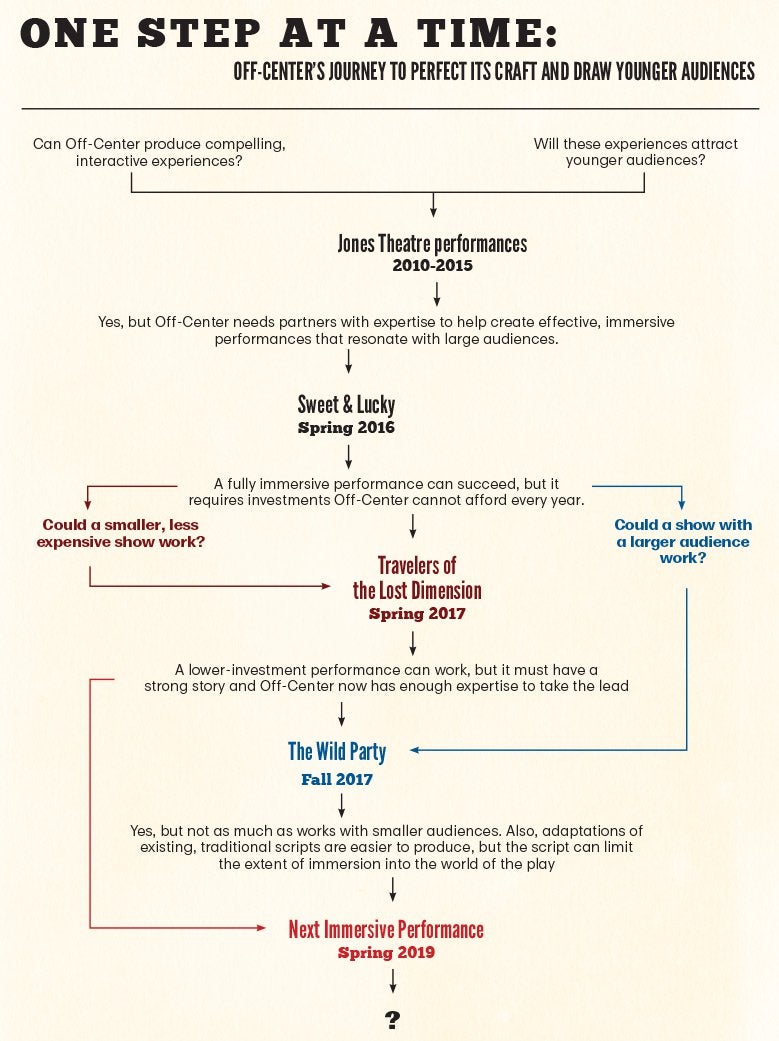

The Denver Center Theatre Company has been engaged in an iterative process of experimentation, evaluation and refinement to bring in more millennials. Watch the video to see how they're using interactive, or "immersive," theater to accomplish this goal.

On a chilly October evening in Denver last year, some 200 people filed into Stanley Marketplace for a performance of The Wild Party, a musical that depicts a debaucherous night in New York City in the 1920s and that has been staged many times since it debuted on Broadway in 2000. But the production in October took place not in a traditional theater but in a 10,000-square-foot former airplane hangar that has been converted into a shopping and recreation center. There were no familiar rows of theater seats facing a stage; the audience sat instead on sofas, benches and bar stools scattered throughout the space. Players meandered around the room, bantering with the audience, showing off card tricks and inviting people to dance. Audience members didn’t just watch; they assumed the role of guests at the party in the play, with many donning Jazz Age regalia such as dropped-waist dresses, beaded headbands, short-brimmed fedoras and boutonnieres.

The performance, produced by the Denver Center Theatre Company, a division of the Denver Center for the Performing Arts (DCPA), was part of a multi-year experiment to help address an urgent concern: Denver Center audiences are aging, even though younger people have been moving to Denver in droves. The average single-ticket buyer at the Denver Center Theatre Company is 50 years old and the average subscriber is 63, despite the fact that millennials, a group often defined as people born between 1981 and 1997, compose the largest age group in Denver.

Since 2010, the Denver Center has been engaged in an iterative process of experimentation, evaluation and refinement to help reverse this trend. The process began when two young Denver Center Theatre Company staffers, Charlie Miller and Emily Tarquin, proposed some additions to the company’s repertoire. Miller, then a multimedia specialist, suggested melding live performances with interactive technologies, while Tarquin, an administrator who has since left the Denver Center, argued for a revival of the company’s idle 200-seat Jones Theatre. Kent Thompson, then the company’s artistic director, saw in these proposals an opportunity to draw younger audiences. He therefore helped create Off-Center, an experimental offshoot of the Denver Center Theatre Company, which produced The Wild Party, and set Miller and Tarquin on a journey of trial, error, analysis and improvement to attract the millennials the company was missing.

Humble Beginnings

Off-Center’s beginnings were humble. Denver Center leaders gave the company a modest $100,000 from DCPA’s it's $65-million annual budget, as well as access to the Jones Theatre and the freedom to experiment as Miller and Tarquin saw fit.

“At first we said, ‘Let’s just see what comes of this,’” recalls Charles Varin, managing director of the Denver Center Theatre Company. “We said, ‘Here’s a space and a little bit of money. You guys do what’ll fulfill you creatively, and we’ll see what happens.’”

A series of small interactive performances followed, all based on millennial preferences identified by an advisory council of young Off-Center supporters and their friends. Some drew enthusiastic young crowds; others were somewhat disordered and left audiences baffled. Each one, however, contributed to Off-Center’s understanding of immersive theater’s ability to draw younger audiences. The Innovation Lab for the Performing Arts, a grant program that helped fund early Off-Center performances, encouraged the company to study audience reactions and draw lessons it could apply to future performances.

“It took us through a process of continuous learning,” Miller, now associate artistic director and Off-Center curator, says of the Innovation Lab. “It taught us how to do research, to question assumptions, to collect data and analyze it, to experiment or prototype, to evaluate it and apply our learning to the next thing.” [fn value="1"]Some of the lessons the Innovation Lab for the Performing Arts drew from Off-Center’s early experiences are documented in a detailed case study the organization published in 2014.[/fn]

A small set of lessons emerged. Off-Center learned that it had to collaborate more closely with artists and performers, set clear audience expectations and find the right balance between interactivity and a clear predetermined storyline. Off-Center used these lessons to expand its horizons, move beyond the confines of the traditional Jones Theatre and test its first big-budget, fully immersive performance, 2016’s Sweet & Lucky.

Sweet & Lucky: A Model Emerges

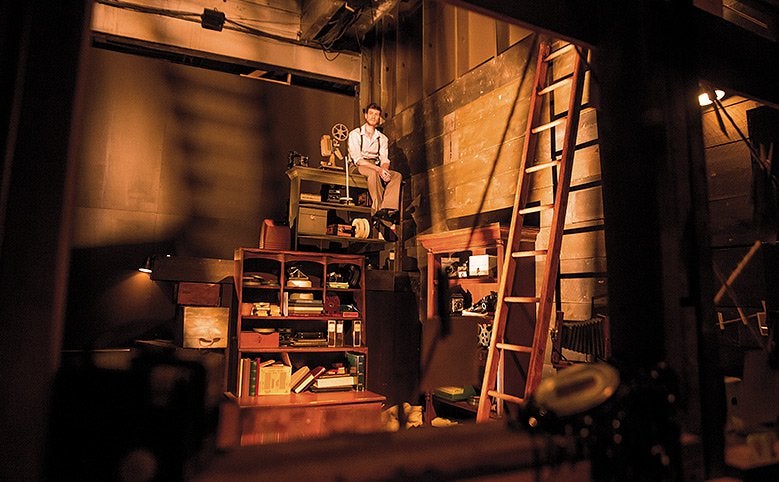

Sweet & Lucky, an $800,000 production, was Off-Center’s most ambitious project yet. It took place in a 20-room performance space that Off-Center built in a 16,000-square-foot warehouse in a northern Denver industrial district. The audience followed a couple’s life by walking through short dream-like sequences in each room. They looked on as the couple baked cookies, attended a funeral, set a table for a dinner party and watched a short movie in the back of a pick-up truck. By the end of the performance, each member of the audience had held a one-on-one conversation with one of the actors, and no two attendees had had the same experience. Once the conversations were over, people could mingle over cocktails in a bar the production team had built in the warehouse loading dock.

The effort required a year and a half of preparation and pushed Off-Center’s artistic and logistical limits farther than any show had before. But the artistic team had past experiences that helped pave the road into unchartered territory.

Prior experience had, for example, taught Off-Center to be cognizant of its limitations. In 2015, Perception, an original immersive performance that combined magic, music, poetry and trapeze, had demonstrated the difficulty of creating a show that allowed for audience interaction yet still hewed to a coherent narrative. Some viewers were confused by Perception; the show entertained, but it lacked the structure some audience members needed to make sense of its many elements. “It was really cool,” says Miller, “but it didn’t have a clear story to connect all the pieces.”

Off-Center needed help establishing a narrative coherent enough to create meaningful experiences for an audience. It therefore commissioned Third Rail Projects, a theater company based in Brooklyn that specializes in immersive performances, to develop Sweet & Lucky and build the narrative foundation in it that Perception lacked.

Third Rail Projects worked closely with Off-Center to build the narrative, hone the tone, create floor plans and determine how the 72-person audience would move through the space.

“It was really a great partnership,” says Miller. “We enabled them to do something on a scale that they’ve never done and they taught us about creating and producing immersive theater—lessons we are able to carry forward in our work.”

Experience had illuminated the need for outside help, but there were other elements of the production that required Off-Center to take a more intuitive leap of faith. Sweet & Lucky was a production at a much grander scale than anything Off-Center had attempted before, and the small artistic team knew it needed help to pull it off. It therefore involved Denver Center’s marketing team from the beginning of the artistic process, a significant departure from the usual practice.

“Historically, it has been more territorial between the marketing and artistic teams,” Miller says. “Artistic doesn’t want marketing telling it what to do, and marketing also doesn’t want artistic telling it, ‘This is my choice, good luck selling it.’”

Such concerns were shelved for Sweet & Lucky. The artistic team needed the marketing department’s help to inform the production and manage audience expectations. Third Rail Projects, for example, sometimes pitched ideas that had worked in Brooklyn but seemed too dark for Denver audiences. The marketing department, which led the audience-research efforts before the production, helped refine those ideas.

“We were relying on Third Rail as the experts on immersive theater,” says Briana Firestone, Denver Center’s director of customer experience and loyalty who was then director of marketing. “But we were coming to the table as the experts in Denver and how things work in our market.”

Firestone, in turn, needed the artistic team’s help to set expectations and calm concerns that could keep a timid theater-goer away. Early collaboration with the artistic team, for example, allowed the marketing department to develop a list of frequently asked questions for the show's website, listing everything from an explanation of immersive theater to the choice of appropriate shoes.

The marketing department also had to help with the logistics of creating the new performance space. Research indicated that younger audiences want to socialize before and after a show, but there were no bars or restaurants close to the venue. “It was in the middle of nowhere,” says marketing director Emily Kent. “So we had to build a bar to make sure [audiences] were having that complete night out that they want.”

The Denver Center Theatre Company had no experience creating such a full-service performance, so Firestone and Kent shouldered new responsibilities. “I had to go get signage permits, I had to work with bartenders, I had to manage a bar,” Firestone says. “That’s not usually my job.”

The results of the effort were stellar. All 89 performances of Sweet & Lucky between May 20 and August 7, 2016, sold out. In post-performance surveys, 94 percent of audiences said the play was “very rewarding” or “extremely rewarding.” Critics called it “brilliant ” and “a brave, original and lovely adventure,” with one raving, “There is magic happening here and you feel it.” The average Sweet & Lucky visitor was 41 and a half years old, 12 years younger than the average visitor at Denver Center shows. Thirty-five percent of the audience was less than 34 years old, short of Off-Center’s original target of 50 percent but a far greater share than the 16 percent Theatre Company shows drew in 2016.

The reviews of Sweet & Lucky led the team to reevaluate its 50-percent target. “At first we were a little disappointed that Sweet & Lucky didn’t come in at that big number,” Firestone says. “We had to take a step back and say, ‘They’re not all 23, but that’s okay.’ These are more adventurous shows, and an adventurous spirit doesn’t have an age to it.”

Sweet & Lucky didn’t cover its costs—it grossed less than half the amount it took to produce—but it met its main goal of drawing younger audiences. “We’re seeing the average age of our patrons coming down, which is what we were intending,” says managing director Charles Varin.

Sweet & Lucky was successful, but it cost more than Off-Center could afford every year. Its success therefore raised two questions:

- Would audiences be as interested in a less expensive, less elaborately produced show?

- Could Off-Center offer an intimate immersive experience to a larger audience and hence reduce per-viewer costs?

Travel, but Don’t Forget the Map

Off-Center took on the first question by producing the lighthearted and improvisational Travelers of the Lost Dimension in spring 2017.

In Travelers, three actors herded up to 45 patrons through a series of skits in the expansive halls of Stanley Marketplace. Performers and participants walked past bars, salons, shops and galleries, stopping every few minutes for a performance in a “new dimension.” Audiences watched a short film in a darkened stairwell, participated in a massage train, posed for group photos and created crayon illustrations in an “art therapy session.” There was no clear narrative, just a series of loosely connected skits that often drew chuckles or quizzical glances from passers-by.

It was a far humbler production than Sweet & Lucky. That show required an elaborate, multi-room performance space; Travelers took place in the public halls of Stanley Marketplace. Instead of an immersive-theater expert from Brooklyn, Off-Center worked with a local comedy troupe. There were no elaborate props or decorations, just tote bags with trinkets like crayons and diffraction glasses that visitors used during the performance.

“Sweet & Lucky was the ultimate large-scale immersive show. We can’t do that every season,” Firestone says. “Travelers is pretty low-fi. It’s definitely scalable to do every year if we wanted to.”

Early results were heartening. The presale sold 750 tickets, nearly half of all tickets available at the time. More than half sold to people who had seen Sweet & Lucky, pointing to a continued hunger for immersive theater. Demand was so strong that Off-Center extended the show by four weeks before rehearsals even started.

Reactions, however, were less exciting. Just 47 percent of audiences considered Travelers a rewarding experience, a 47 percentage-point drop from Sweet & Lucky. Young children enjoyed it more than the millennials Off-Center targeted. The show’s “net promoter score”—a scale from minus 100 to 100 that measures audiences’ eagerness to recommend the show to others—was minus 23, a sharp drop from Sweet & Lucky’s 85.

Surveys pointed to two reasons for the tepid reaction. First was the success of Sweet & Lucky. Publicity materials for Travelers used a playful comic-book-style motif to distinguish the show from Sweet & Lucky. But surveys suggested that audiences were still searching for a deep experience that Travelers was not designed to deliver. “I think it’s just because Sweet & Lucky was so popular,” says Firestone. “It was such a visceral experience for so many people, they wanted [Travelers] to be like that.”

The show’s popularity with children, however, offered an opportunity to improve the experience. The marketing team started pushing the performance towards families instead of millennials and played up the silliness of the show. It even added a line to the online FAQs stating that Travelers was nothing like Sweet & Lucky. The result: Though the net promoter score was still low, it increased by 16 points, and audiences later in the run appeared happier than those in the beginning.

“Early audience feedback was the direct input that caused us to make that shift,” says Kent. “The research helps us be nimble and helps us keep learning.”

The second problem was trickier and likely contributed to the stubborn net promoter score. “The biggest audience complaint about Travelers was that there wasn’t enough stories,” Miller says. Surveys suggested that audiences struggled to make sense of the play’s disjointed experiences. “The best pieces,” complained one reviewer, “have nothing to do with the tissue-thin storyline.”

The experience offered two lessons for Off Center. First was the importance of a clear narrative. “Before Sweet & Lucky, we had this assumption that millennials don’t care [about the story], they just want it to be weird and fun,” says Kent. “But they actually really care about the story.”

Second was the value of the Off-Center staff’s own judgment. Miller had concerns about the lack of a narrative when the creators of Travelers first presented their ideas. But he hesitated to be too assertive about them. The Off-Center team tended to defer to the vision of its creative partners, a tendency Miller felt he could have constrained.

“I regret not speaking up as loudly as I could have when I had early concerns,” Miller says. “By the time we saw the show on its feet and recognized that it needed a clearer through line, there wasn’t enough time to make meaningful changes to the show.”

Expanding the Party

Off-Center applied some of these lessons to The Wild Party, the Jazz Age musical in the former hangar in October. Miller and company selected an existing play with a clear storyline. They produced the show in the Hangar at Stanley Marketplace, a dedicated private space rather than the public hallways that Travelers audiences had found distracting. And Stanley Marketplace provided the drinks so the team could avoid the hassle of a liquor license and the logistics of building a bar.

The question for this performance was about the balance between the size of the audience, the interactivity of the performance and the intimacy of the experience. Sweet & Lucky had created a meaningful experience for an audience of 72 that moved through an elaborate multi-room set. With The Wild Party, the team set out to see whether it could deliver as memorable an experience in a single room for a stationary, much larger audience of 208.

“Can we make it feel immersive?” Varin asked. “Can we make it feel personal? Can we make it feel like it’s engaging and interactive? Those are the questions we’re exploring.”

Miller selected The Wild Party in part because of the opportunities it offered for audience interaction. “The top priority was that the audience needs to have a clear role in the story,” he says. “What I loved about The Wild Party is that the audience can be guests at the party. That informs why you belong in the space, how you interact with the characters, and it’s essential to the story.”

The team also capitalized on the show’s proximity to Halloween. It encouraged visitors to dress in their 1920s best, further immersing them in the universe of the show.

The marketing team continued to use text and design in publicity materials to establish basic expectations and offer hints about the emotional experience. Set design for a stationary audience was largely problem-free for the Denver Center’s experienced production teams, although the move from a traditional theater to a custom-built space did complicate sightlines for some viewers.

Results were more encouraging. Nearly all performances sold out. The net promoter score went up to 59, still short of Sweet & Lucky’s 85 but far better than the minus 7 of Travelers. Thirty-nine percent of the audience had visited another Off-Center performance in the last year, pointing to continued demand for the new type of theater.

“Over 85 percent of our overall database comes once every two years, or not even,” says Emily Kent. “So for people who came to Sweet & Lucky 18 months ago, some of them went to Travelers and now they’re back for this. That’s huge.”

The experience confirmed two of Off-Center’s hypotheses about its audience. First is the importance of the story, regardless of the results of focus groups. “In focus groups the audience was telling us that they want something entertaining and light and a good time and a party atmosphere,” says Varin. “What we saw, at least from Sweet & Lucky to Travelers to The Wild Party, is that they want those things, but they also want a strong narrative.”

The second hypothesis: net promoter scores suggest that a traditional play adapted for a nontraditional performance can engage audiences, but it may not be a substitute for a performance specifically designed for an interactive experience. “Staging [an existing] script immersively may be a little easier,” says Miller, “but it can’t be as fully immersive as it would be if you create something original.”

Looking ahead

Off-Center will continue to experiment with new types of performances—some elaborate, others sparse; some playful, others dark—to determine how it can create meaningful experiences as efficiently as possible. An essential element Off-Center intends to explore more deeply in the future is financial sustainability. Ticket sales cannot cover all of Off-Center’s expenses, so it currently relies on donations from supporters and philanthropies such as The Wallace Foundation. The Off-Center team hopes, however, that if it can perfect its craft, draw younger audiences and help meet the Denver Center’s larger audience-development goals, it will draw more support from DCPA, reduce reliance on external donors and hence ensure its longevity.

“The goal is not to have Off-Center completely supported by ticket sales alone,” says Varin. “It’s more about the level at which [DCPA] should be subsidizing this work. The main question is, ‘How does this fit into the organizational priorities around audience demographics, and is the budget reflecting that?’”

In the meantime, Off-Center is continuing to experiment while building on experience. It plans to produce its next original, fully immersive Sweet & Lucky-style production in Spring 2019. It has commissioned a writer to create a grittier hip hop-themed show and will see if it can increase the racial diversity of its audience. This time, however, it is more confident in its ability to create the interactive experience itself. “We are now the experts in immersive theater,” Miller says of plans for the next show, “and we are guiding [the writer] in doing that.”

This article and video are part of a series describing the early work of some of the 25 performing arts organizations participating in The Wallace Foundation’s $52 million Building Audiences for Sustainability initiative. Launched in 2015 in response to concerns about a declining audience base for a number of major art forms, the endeavor seeks to help the organizations strengthen their audience-building efforts, see if this contributes to their financial sustainability, and develop insights from the work for the wider arts field.

Start a Discussion

The purpose of this Discussion Guide is to help arts administrators, board members, and arts practitioners working within varying disciplines and with a range of budget sizes to better understand and apply lessons from another institution’s experience to their own context. The guide can serve as a teaching aid for small-group discussions, as well as individual study. It is designed to be used in conjunction with the article and/or video.

Stories in Building Arts Audiences