The idea seems simple—give low-income kids books over the summer and their reading will improve. As Harvard education professor James Kim knows, there’s a lot more to it than that.

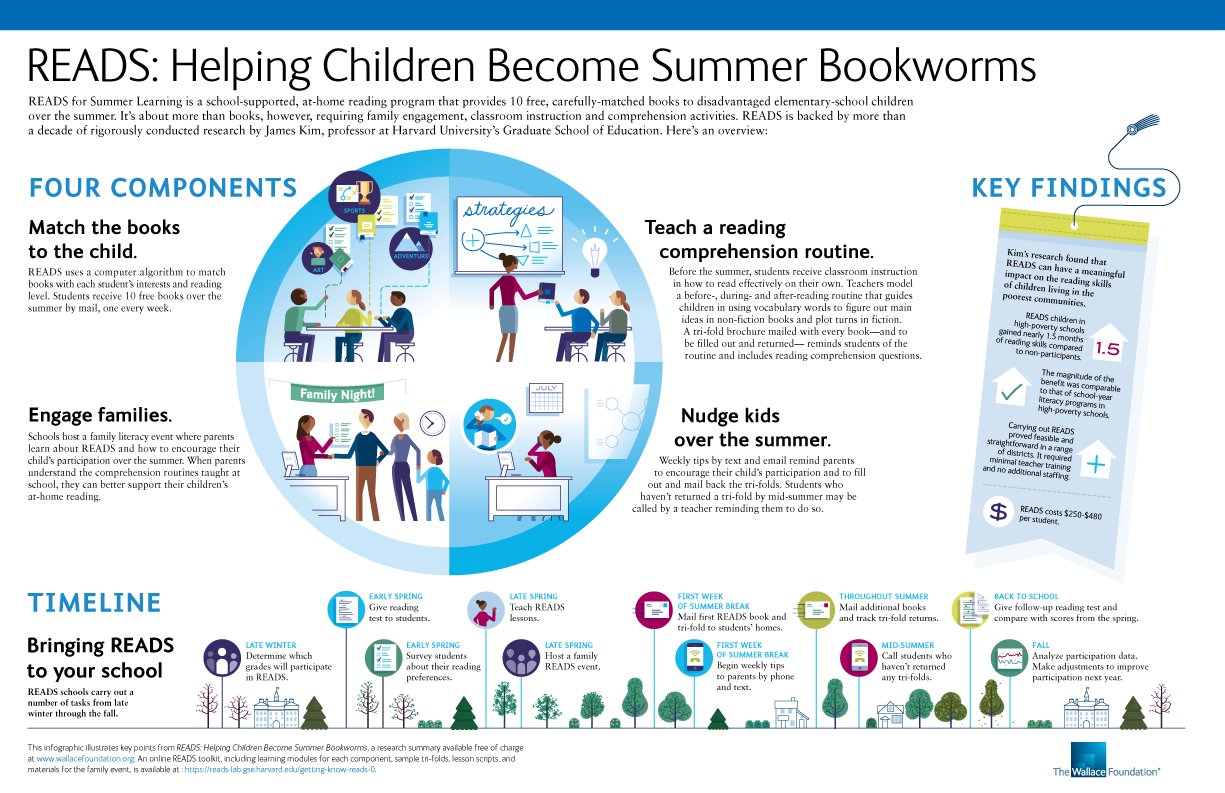

Kim is the key person behind READS for Summer Learning, a school-run, home-based program shaped by 10-plus years of research and experimentation. Over time, Kim and his colleagues developed a program which, through a combination of instructional support, family engagement and books carefully matched to the reading levels and interests of young readers, helped its participants in high-poverty elementary schools gain nearly 1.5 months of reading skills on average compared to non-participants. A new Wallace report describes READS, which received support from the foundation. (Click on the thumbnail below to view the infographic.)

The READS research was all-consuming. Kim even packed and hand-delivered boxes of books to schools participating in his studies. Still, the hard work was worthwhile, considering its purpose, according to Kim. “READS is designed to impact a child’s head, heart and hands,” he says. “It helps kids read for understanding, inspires their love of reading and causes them to want to get their hands on more and more books.”

Now, educators want to get their hands on READS. Kim has fielded inquiries from school district leaders to classroom teachers. This past year, he conducted webinar training with a group of school literacy facilitators in Michigan. A colleague ran a similar workshop with librarians in Massachusetts. Interest has also come from nonprofit organizations that bring services to schools, such as tutoring and book fairs.

Kim’s work follows him home: His three kids are entering second, third and fourth grade. What’s one of their favorite books to read together? Kate DiCamillo’s Mercy Watson series, starring a hilarious pig. “While we’re on the theme of pigs, I love Charlotte’s Web too!” Kim adds.

Kim’s work follows him home: His three kids are entering second, third and fourth grade. What’s one of their favorite books to read together? Kate DiCamillo’s Mercy Watson series, starring a hilarious pig. “While we’re on the theme of pigs, I love Charlotte’s Web too!” Kim adds.

Below, he talks more about his research and summer learning.

You started your career in education as a middle-school history teacher in the 1990s. How did that experience spark your interest in researching summer reading loss and possible solutions?

At my school, kids learned about colonial history to the Civil War in sixth grade. I covered Reconstruction to the present in seventh grade. When kids returned to school in September, some clearly knew a lot about history and some seemed to have forgotten much of what they learned about the Civil War, which was covered just three months ago. As I probed, it became clear that many of my disadvantaged students did not have enriching summers. They read few books and lost a lot of ground academically. This first-hand experience gave me the initial burst of inspiration to think of a low-cost solution to summer learning loss.

Your research on READS spans more than a decade. There was a trial-and-error approach to your work as you figured out the key components of the program. What surprised you most?

I call the trial-and-error approach the fusion of “strategic replication” and “heroic incrementalism.” That is, I wanted to stick with a program of research long enough to build on what worked and to make changes to what didn’t. This approach yielded a lot of surprises, but that’s what makes science fun—having your assumptions challenged and continually building knowledge.

One surprise was disappointing. In an early READS study with my colleague Jon Guryan, an economist at Northwestern University, we let kids select their own books rather than matching them with books based on their reading level and book tastes. Too many kids picked really hard books. They did no better on a follow-up reading test than their peers who hadn’t been part of READS. We shouldn’t think of this as a failure, though, because it’s critical to know what doesn’t work.

A second finding is more optimistic. In our last RCT [randomized controlled trial] of READS, we compared core or traditional READS with adaptive READS. In the core READS program, we instructed teachers to implement the core components with fidelity. In the adaptive READS model, we allowed for structured adaptations so teachers could make changes to help make the program work better with their kids. The adaptive READS program worked better, improved student engagement and ultimately students’ reading comprehension outcomes. We were surprised and gratified to see that the adaptive READs model could work well in high-poverty schools (75 percent to 100 percent of students eligible for free lunch) particularly when teachers had implemented core READs for at least one year.

Summer seems to be an under-utilized time for learning. Why is that?

One challenge is that educators already have a crowded agenda. There’s already so much that a superintendent, principal and teacher have to accomplish during the school year. I think summer is a peripheral concern. In addition, educators typically don’t have the same level of accountability or funding for programs outside school, especially during the summer. My hope is that more educators invest in low-cost and scalable solutions, whether READS or some other program, for stimulating learning outside school in the summer.

Mobile technology and usage have evolved significantly since you started your research. According to Pew Research, 92 percent of U.S. adults earning $30,000 or less own a cell phone of some kind. Two-thirds carry smartphones. Can you see READS going digital, with kids reading books and answering comprehension questions via a READS app?

Great question. I’ve always felt that READS should evolve to meet the needs of educators, parents and children. And one great need today is developing digital solutions that are low-cost and effective in promoting summer learning. A READS app is a promising idea because it could provide parents and children more real-time feedback and encouragement. It might include games and incentives to further stimulate summer reading at home. I’d like to develop and try out some of these ideas. Stay tuned for updates on our website as we develop digital tools.

As a father, how have you encouraged good reading habits in your children?

I think the key word is habit. Most nights, I read aloud to my kids, and I typically choose (or at least try) a book that my kids might not read on their own. One of my favorites is a series of biographies for kids by Brad Meltzer called Ordinary People Change the World. My kids wouldn’t, on their own, pick up a book about Albert Einstein or Abraham Lincoln, but I like to read these biographies to them. In many ways, this is exactly what we do in READS. Educators provide lessons about a narrative chapter book and teach kids a simple routine to engage with fun books about animals, natural science and famous people. Ultimately, to form good reading habits, kids need caring teachers and parents to open up new worlds of knowledge that are engaging and fascinating.

Photos by Claire Holt. Main photo: James Kim reads with his children.