This post is the first of a series profiling the University of Connecticut’s efforts to strengthen its principal training program. The university is one of seven institutions participating in Wallace’s University Principal Preparation Initiative (UPPI), which seeks to help improve training of future principals so they are better prepared to ensure quality instruction and schools. A research effort documenting the universities’ efforts is underway. While we await its results, this series describes one university’s work so far.

In this post, Dr. Richard Gonzales, director of the university’s educational leadership preparation programs, describes why the university decided to participate in the initiative, its general approach to the work and the effects it is seeing so far. Other posts include descriptions of efforts to redesign curricula and internships, students’ and faculty members’ views about the new design and the ways in which the university works with community partners to ensure it is meeting their needs.

These posts were planned and researched before the novel coronavirus pandemic spread in the United States. The work they describe predates the pandemic and may change as a result of it. The University of Connecticut is working to determine the effects of the pandemic on its work and how it will respond to them.

Change. It is a topic fundamental to schools and leadership. Since the mid-1980s, it has been a central theme in the discourse of educational reform. Today, it is a day-to-day reality for principals and superintendents leading public schools. Graduate education programs accordingly include, if not feature, the concept of change in coursework, assigned readings and capstone projects.

Still, change is not yet a part of the culture and operating norm within higher education. There is a gap between espoused theory and lived action in educational leadership graduate programs. Many profess that change is instrumental to organizational improvement. Yet, a vast majority of those programs have not changed substantially for decades. Here, I share my perspective of leading and supporting the effort to redesign the UConn Administrator Preparation Program, with the hope that our work can serve as an informative example of what bridging the gap between theory and practice can be like.

Why change what is (apparently) working well?

The University of Connecticut Administrator Preparation Program (UCAPP) was doing well by any reasonable measure in 2016. Enrollment was steady, alumni satisfaction was quite high and at least 95 percent of every graduating cohort in the previous five years passed the state certification exam and completed the program on time. Encouraging as they were, those indicators weren’t enough for us at UConn. We viewed the Wallace University Principal Preparation Initiative (UPPI) as an opportunity to critically examine our program and identify ways in which we could improve.

A key step in our journey was completing the Quality Measures self-assessment. We used the instrument to identify what we were already doing well and highlight ways that we could improve. The self-study process helped us identify three improvement priorities for redesign.

The most significant takeaway was that we could not speak with confidence to our graduates’ level of competence in core leadership domains such as instructional leadership, talent management and organizational leadership. We accordingly started our redesign process by defining project-based tasks which would assess our students’ applied knowledge, skill and judgment. Our practical theory was that such tasks would give students the opportunity to assess and demonstrate their skills in these areas and allow us to ensure they were ready to lead schools.

We also realized we needed to do a better job of monitoring student progress and graduate outcomes. Information is useful only if you have systems in place to use it to evaluate what’s working and guide continuous improvement. We had no data systems in place, so we are developing the Neag School Educator Preparation Analytics System in partnership with the UConn Graduate School, local school districts and the Connecticut State Department of Education. This database will allow us to answer questions about our students’ performance while in our program as well as their career pathways from undergraduate degree to district-level leadership positions.

Developing this data analytics system forced us to face an uncomfortable fact and our third priority for improvement: our student demographics were not representative of the educator workforce. Although nine percent of certified educators in Connecticut are persons of color, Black or African American and Latino educators typically constituted only one to two percent of our enrollment over the past 10 years. Actively recruiting educators of color and promoting their attainment of and success in school and district leadership roles is now a top priority to promote equitable workforce outcomes in our state.

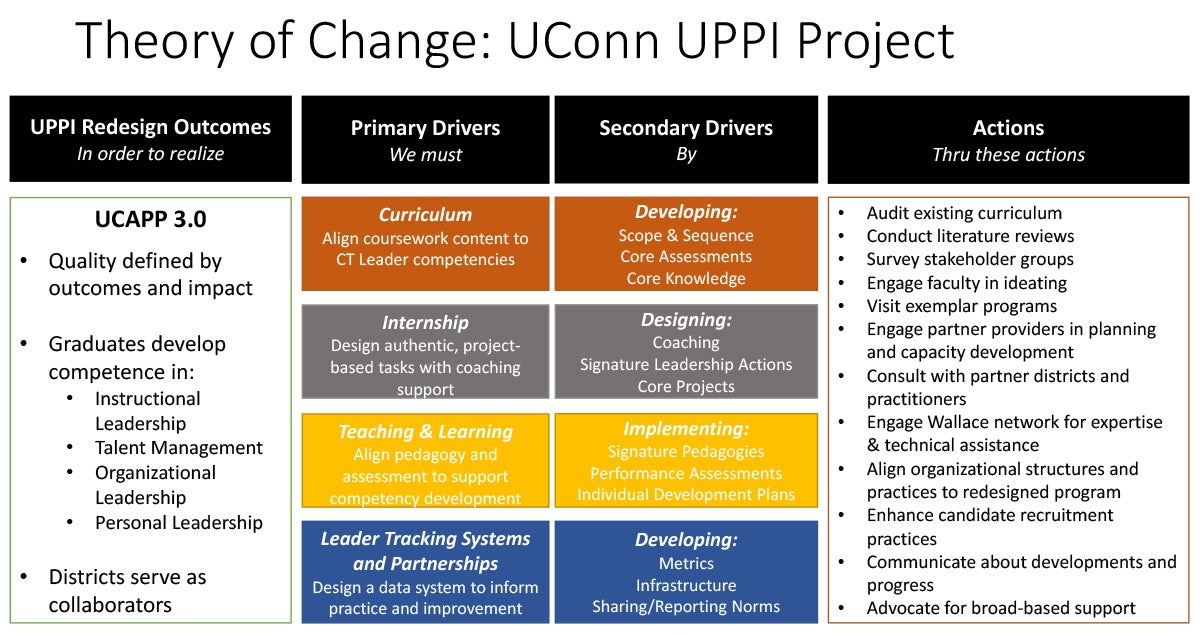

Inspired by the Carnegie Foundation’s work in the area of continuous improvement, we developed a practical theory of change, referred to as a logic model in UPPI, for the work ahead. The fundamental shift for us at UConn is that success used to be measured by delivering on the promise of a quality holistic preparation experience. Going forward it will be measured by student and graduate outcomes and the impact of our partnerships to improve the leadership pipeline across Connecticut. Redesign for us accordingly entailed changing the program of study, the curriculum, our instructional approach, expectations for student learning, the structure of the practicum experience and developing systems for collecting and using program data to inform implementation and planning.

Improvement in action: the example of core assessments

Perhaps the best example of the translation of theory to practice is the core assessments. We underwent similar processes to increase diversity and develop data systems, concepts that will be discussed in other blog posts in this series.

We designed the core assessments to address four shortcomings we uncovered in the Quality Measures self-assessment:

- Most “final” assignments asked students to write papers and had few connections to lived leadership experience in schools.

- Students developed several plans for school improvement, but never implemented them.

- Students only did work aligned to course topics (supervision, curriculum, etc.) during the semester of the course, rarely returning to them again.

- We didn’t know the extent to which students were making connections among course topics and assignments.

The core assessments in our restructured program seek to tie together previously disparate parts of our program. They are a set of leadership tasks students must complete and use to measure their competencies in the domains of instructional leadership, talent management and organizational leadership. Students no longer learn about one skill or competency and move on. The core assessment tasks allow them to practice authentic principalship work in schools as part of the clinical experience.

Students first conduct an organizational diagnosis to identify what is working well in a school and potential areas of improvement. Next, they formally observe a teacher’s lesson and provide constructive feedback to promote student learning. They then facilitate a professional learning community with a teacher team or the entire school. For the capstone project, each student leads a group of stakeholders in a school improvement initiative.

Courses now align content and scaffold experiences to support students’ completion of each task independently within prescribed timelines. A leadership coach guides each student through the Investigate-Plan-Act-Assess-Reflect process for each task to promote leadership learning.

Encouraging signs of adaptation

While it is too early to tell the extent to which we will achieve our goals, it is evident by the way we engage in the daily work of preparing our principalship candidates that we are a different program. Heifetz and Laurie (1997) describe adaptive challenges as those that organizations face when they undergo substantial change. They argue that adaptive challenges require organizations to “clarify their values, develop new strategies, and learn new ways of operating” by discussing, debating and problem-solving in real time while engaging in the core work. At UConn, the early adaptive responses center around collaboration and communication to deal with the adaptive challenges of implementing a new program of study and a substantially different approach to preparing aspiring school leaders.

The first noticeable change is that communication happens more frequently and openly to plan and teach the new courses. In the past, instructors might have had a pre-course meeting to discuss the syllabus and an end-of-course debrief discussion. In the restructured program, instructors are communicating weekly. They are sharing preparation notes, presentation slides and observations about student sensemaking. In effect, they are using these data to make real-time adjustments to content and instructional practices. For example, three instructors teaching a talent management course recently exchanged ideas for how to facilitate discussion—online and in class—about providing evidence-based feedback to teachers. In their discussion, they considered how this practice would be helpful to the students in demonstrating proficiency in the core assessment’s teacher-observation task, which measures practical knowledge, skill and judgment of this foundational principalship practice.

In addition to communication happening more frequently about coursework, we are also discussing “big picture” program considerations differently throughout the organization. As one instructor recently commented, the new program requires us to think about the whole program, not only a single class, assignment or experience. This has implications for how we structure opportunities to plan, ask questions and solve problems systemically. Understanding the conceptual and practical connections between the coursework and the clinical experience provides an excellent example. It is no longer a matter of “Who does what?” or “Where does that happen in the program?” Instructors are starting to wonder and ask aloud: “How does what I’m responsible for connect to what came before, what else is happening right now and what comes next?” Leadership coaches are similarly mindful of when things happen in schools and districts during the academic year to guide the interns’ thinking and action accordingly.

Our students are also developing a voice and informing implementation, a phenomenon which was virtually non-existent in the past. New organizational norms, we hope, encourage students to speak up about what is working for them and what is not. For example, the first cohorts to enroll in the restructured program recently challenged our espoused program commitment to equity (using language from our handbook and coursework) by pointing out that the vast majority of instructors and guest lecturers work in suburban districts. They argued that including urban leaders’ perspectives would enhance their preparation experience. This feedback helped us realize that we could and must do better immediately and from now on to ensure proportionate representation.

Our case is an example that it is possible for higher education organizations to close the gap between professing change theory and living it in action. We look forward to the continued challenge of reconciling our organizational values with new ways of operating.

Stories From UConn Principal Prep Program