What Do I Need to Know About School Leadership?

Key Takeaways

- Principals are key to improving K-12 education. They can enhance teaching, school climate, and other basics of high-quality schools.

- Principal pipelines that are “comprehensive” and “aligned” can lead to significant benefits in student reading and math. "Comprehensive" means pipelines cover a range of actions districts can take to shape principals. “Aligned” means the actions reinforce one other.

- Four key behaviors characterize effective principals. These behaviors can also work to advance equity in schools.

- University principal preparation programs can be updated to reflect the latest evidence about what works in school leader training.

- Districts can reshape the principal supervisor’s job so it focuses less on handling administration and more on helping principals grow.

- States can use their authority in matters like principal licensure and oversight of principal preparation programs to improve school leadership.

Why School Leadership Matters

School leadership is second only to classroom instruction in school-related impacts on student learning. That's according to a landmark study, How Leadership Influences Student Learning. A teacher, however, affects only a single classroom. A principal influences student learning schoolwide. Research links principal effectiveness to student achievement, better student attendance, and less exclusionary discipline. It is also linked to lower teacher turnover and higher teacher satisfaction.

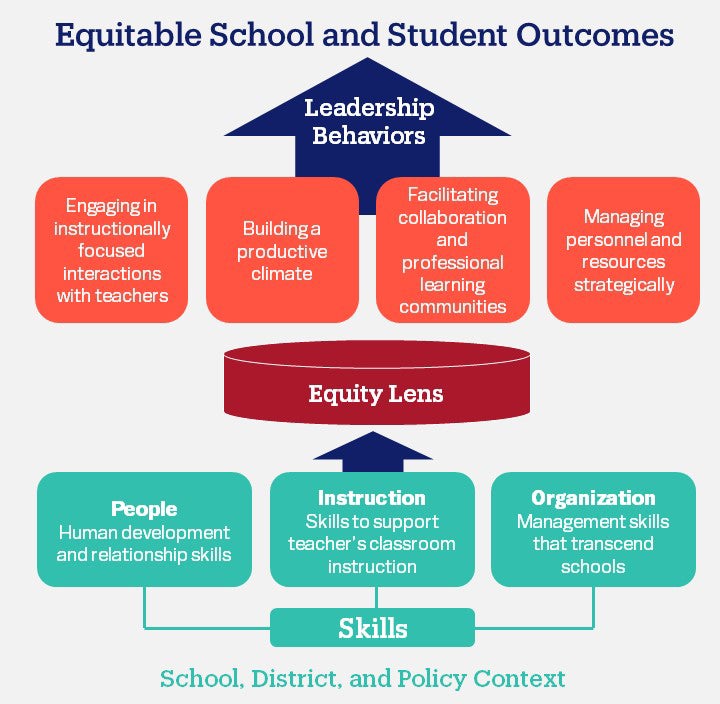

How do principals improve schools? A 2021 research synthesis, How Principals Affect Students and Schools, identified these four key behaviors:

Engaging with teachers on instruction. Effective leaders observe classrooms and provide teachers with useful feedback, among other practices.

Creating a productive school climate. Strategies include building respectful relationships and supporting teacher leadership.

Forging collaboration. High-quality principals provide teachers time to discuss how to better support students and improve instruction.

Managing resources and personnel well. Effective leaders are skilled managers of a school’s facilities, budget, and safety. They know how to hire, place, and keep good teachers. They also manage their own time to focus on instruction.

Strong Pipelines Can Produce Effective Principals

Districts can benefit student achievement with a comprehensive system to develop principal leadership. That was a major finding from the Principal Pipeline Initiative. This six-year effort was launched in 2011 and supported by The Wallace Foundation.

A RAND Corporation study, Principal Pipelines: A Feasible, Affordable, and Effective Way for Districts to Improve Schools, looked at results in the six large school districts that took part in the effort They all built pipelines to prepare and support new principals. The study compared about 1,100 pipeline schools to 6,300 non-pipeline schools in the same states as the pipeline districts.

Results were eye-opening. Pipeline-district schools with newly placed principals markedly outperformed comparison schools after three years. The difference was more than 6 percentile points in reading and almost 3 percentile points in math.

Benefits kicked in quickly. The first cohort of principals saw outperformance in student achievement during the second year on the job. And effects were large for schools in the lowest quartile of achievement.

Principal retention rose at pipeline schools, too. Pipeline schools had nearly eight fewer losses for every 100 newly placed principals than the comparison group.

A related study described how the districts conceived of and built their pipelines. Policy Studies Associates' The Principal Pipeline Initiative in Action said the districts were able to carry out the needed work “to a striking extent.”

"Comprehensive, Aligned" Pipelines: What That Means

The pipelines were "comprehensive" because they covered a wide-ranging set of actions school districts could take to develop and support effective school leadership:

- Rigorous leader standards

- High-quality pre-service preparation

- Selective hiring and placement

- Apt on-the-job evaluation and mentoring

- Principal supervision focused on helping principals grow

- A data system to track the qualifications and progress of principals and candidates

- Mechanisms for sustaining the pipeline.

These actions, known as "domains," were also aligned. That means they were connected to and reinforced one another. For example, leader standards informed how aspiring principals were trained and how sitting principals were supported, evaluated, and supervised.

Pipelines: Affordable and Sustainable

Pipelines cost on average 0.4% of district budgets per school year in the six districts.

A follow-up study found the pipelines intact and valued two years after the initiative ended. This suggested that pipelines had staying power.

The Principal Pipeline Podcast

Find out what it takes to build an effective principal pipeline. Hear about everything from the key role of leader standards to the findings of the Principal Pipeline study—and the parts districts, universities, and states play in shaping sound school leadership.

We found no other comprehensive district-wide initiatives with demonstrated positive effects of this magnitude on [student] achievement.

Leading for Equity

A growing body of research describes leadership for educational equity and what characterizes it. The four behaviors of effective school leaders identified in How Principals Affect Students and Schools could promote equity--if carried out with an equity lens. Take the behavior of building a productive school climate. What steps could an equity-minded principal take to ensure that the climate supports every student? There is a wide range of possibilities. They include communicating high expectations for undocumented students and closing racial discipline gaps.

The racial and ethnic make-up of the student K-12 population has changed markedly in recent decades. But the composition of the principal workforce has failed to keep pace. Consider the following:

- In 1988, about 9 percent of students were Hispanic.

- By 2016, that figure was 23 percent.

- Yet the percentage of Hispanic principals grew far more slowly, from 3 to 8 percent.

This think piece by a group of scholars led by Columbia University's Mark Anthony Gooden provides considerations for how to embed equity in each key component of a principal pipeline.

Wallace's current major effort in school leadership is the Equity-Centered Pipeline Initiative. Eight large school districts around the country are exploring how to build principal pipelines that produce school leaders who can advance educational equity and lift student learning.

Leadership Through an Equity Lens

An equity lens could prompt principals to ask themselves questions. How will my actions remove barriers and create opportunities for historically underserved groups? How will they promote access to critical resources and supports for the success of all students? How will they confront institutional factors that may be inhibiting members of the school community from achieving their full potential?

—Adapted from How Principals Affect Students and Schools

Improving University Principal Preparation

University training for future principals has not kept up with the job’s growing demands.

In 2016, The Wallace Foundation launched an effort to try to improve principal preparation. Seven universities in seven states participated in the University Principal Preparation Initiative.

The initiative led to the meaningful redesign of the seven programs. That’s according to a study by RAND. Researchers found that universities can defy expectations about institutional resistance to change. They can collaborate with school districts, state organizations, and others to adopt evidence-based features of high-quality programs.

The teams working on the effort improved their programs by:

- Aligning the curriculum with national standards and state requirements for principals

- Ensuring changes to instruction were informed by district needs and the real work of principals

- Emphasizing practical experiences and job-related activities that reinforced coursework. This included providing stronger coaching.

- Having all participants begin and progress through the program with a cohort. This enabled participants to develop a peer support network that continued after program completion.

- Seeking to diversify the preparation programs. They did so in part by working with districts to recruit candidates from historically underrepresented groups.

The Learning Principals Need

A research synthesis by scholar Linda Darling-Hammond and her team links some types of principal learning to better outcomes for students and schools. The five most important content areas are:

- Leading instruction

- Managing change

- Developing people

- Shaping a positive school culture

- Meeting the needs of diverse learners.

Principals also need on-the-job learning. That includes preservice internships that provide instructional leadership experiences. In addition, sitting principals need coaching and mentoring.

While learning for principals has improved over the last decade, gaps remain. The report found that most principals wanted more learning on nearly all topics. Few had access to high-quality internships, coaching, or mentoring. Nationwide, principals serving high-poverty schools were the least likely to report high-quality learning opportunities.

[I]mproved research can continue to build knowledge about how to best develop high-quality principals, and enhanced policies can create a principal learning system that will better serve principals and, ultimately, all children.

A New Role for Principal Supervisors

Principal supervisors have traditionally focused more on handling administrative matters than improving instructional leadership. To better support principals, more districts are redesigning the job. Six large school districts did so as part of the four-year Principal Supervisor Initiative, funded by the Wallace Foundation. Principals gave the effort high ratings.

Actions districts took included:

- Reducing the number of principals their supervisors oversaw from an average of 17 to 13

- Training principal supervisors to recognize high-quality instruction

- Coaching on specifics like how to give feedback to principals

- Planning to organize the central office to better support supervisors.

How States Can Improve School Leadership

States can influence the quality of school leadership. That’s according to research by political scientist Paul Manna that draws from sources including the experiences of states that have focused on developing stronger principal policy. He points to three actions to move state policy.

One is to evaluate how much importance state education policy places on principal development. Many states focus on teacher quality and overlook school leadership.

Another is to pursue improvements in one or more of six arenas where states can play a useful role:

- Adopting principal leadership standards

- Recruiting aspiring principals

- Approving and overseeing principal preparation programs

- Licensing new and veteran principals

- Supporting principal professional development

- Evaluating principals.

The third is to identify potential obstacles to policy improvements and strategize on ways to overcome them.

Making More of the Assistant Principal Role

Principals can’t do it all. That may be one reason the number of assistant principals (APs) has skyrocketed. More than half of U.S. schools had APs in the 2015-2016 school year, compared with about one-third of schools in the early 1990s.

The AP job has become a more common steppingstone to the principalship. About 75 percent of principals had AP experience in the 2015-2016 school year. That compares with about 50 percent in the late 1980s.

Research by a team from Vanderbilt University and Mathematica in The Role of Assistant Principals: Evidence and Insights for Advancing School Leadership suggests districts could make more of the AP role. Effective assistant principals have the potential to help schools improve academic outcomes, school climate, and educational equity.

They could also increase the racial, ethnic, and gender diversity of the principal cadre. People of color are underrepresented in the principalship. Across six states researchers looked at, 24 percent of APs were people of color vs. 19 percent of principals and 34 percent of students. Women accounted for 77 percent of the teacher workforce and 52 percent of the AP and principal workforce.

Finally, assistant principals could strengthen the pipeline of future principals. Principals could help by providing APs with opportunities to practice instructional leadership.

Featured Resources