When the COVID-19 pandemic shut down live performances last spring, Anna Glass, executive director of the Dance Theater of Harlem (DTH), said the company was thrown off balance but still needed to respond to its changed circumstances. So, despite having little technical knowledge, equipment or experience with virtual presentations, staffers quickly started to prepare and post online digital dance performances. Improvised though it was, this attempt to reach people produced an unexpected result: the discovery of a previously unknown global audience, stretching from California to the Bahamas and Brazil.

“What we were most shocked by was to see how beloved this institution is worldwide. That was a surprise because DTH has been through a lot of turmoil,” Glass said, referring to a period from 2004 to 2012 when financial difficulties shuttered the venerable dance company. “But we were surprised to find that having been out of sight for a while did not mean we were out of mind. There was a hunger to see what we are and what we do.”

Glass said the experience of creating those digital performances has now inspired a stronger desire to find and engage with audiences and to strengthen relationships within and outside of the company. “We had success,” she said of the quick pivot and changed operations during the pandemic. “Not from a financial standpoint, but in giving us a new platform to tell our stories. That lesson has been worth its weight in gold.”

Dance Theater of Harlem’s experience is not an anomaly. Many arts and cultural organizations over the past year have experimented with new ways to engage their audiences and, frankly, survive.

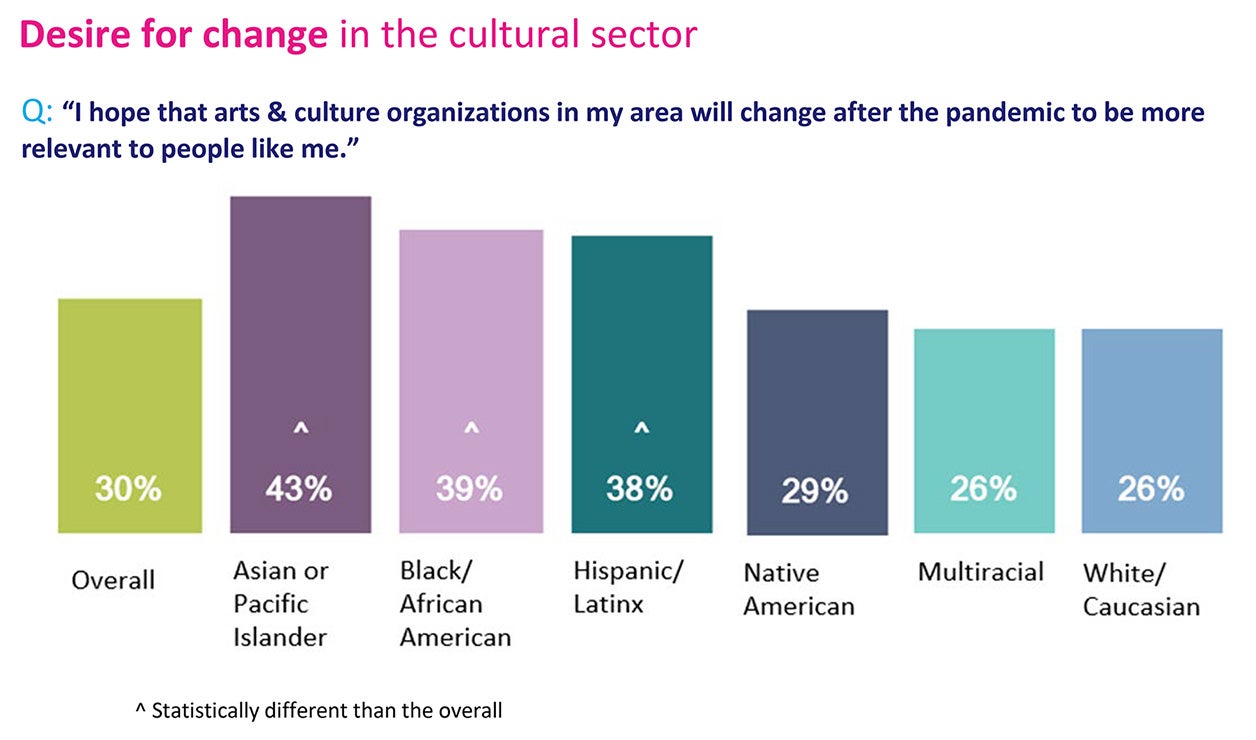

Under the stresses of the pandemic, economic insecurity and a national reckoning with racial justice, audiences, too, have been seeking out ways (especially in online offerings) to find community through the arts. This desire for connection was borne out in a broad survey conducted last year during the early months of the pandemic and described in a report, Centering the Picture: The role of race & ethnicity in cultural engagement in the U.S., by Slover Linett Audience Research and LaPlaca Cohen, an arts marketing company. The researchers surveyed 124,000 people from different racial and ethnic groups from April 29 to May 19, 2020, to find out how they interacted with arts and culture organizations and what changes they might like to see. The responses generally struck three overriding themes:

- Organizations could become more community- and people-centered;

- They could offer more casual and enjoyable experiences; and

- They could provide more engaging and relevant content that is reflective of the communities they serve.

Further, BIPOC (or Black, indigenous and people of color) respondents were even more likely than white respondents to express an interest in changes in the arts and cultural organizations they frequented, reflecting trends that had already been under way in many communities.

At the Nexus of Art and Community

These themes and the survey itself provided an anchor for the fourth edition of Wallace’s Arts Conversation Series, which began with the question: How can organizations respond to what their communities need most, especially in light of the continuing pandemic? Glass was one of the panelists.

Nancy Yao Massbach, president of the Museum of Chinese in America, in New York City, and also one of the panelists, said the theme of being community centered resonated with her organization as well, adding that the museum staff felt a keen need to remain connected with a community suffering under the lockdown. “It’s not just a desire for changes to make the museum more accessible,” she said. “It is an urgency.”

Noting that the museum’s online offerings on the Chinese community’s experience in the United States and artifacts relating these Chinese-American stories, all free, had experienced a 10- to 20-fold increase in viewers since the pandemic, Massbach said she and others at the museum did not want this new engagement to be temporary but to continue once venues reopened. Massbach’s words were echoed by Glass and Josephine Ramirez, executive vice president of The Music Center in Los Angeles, the third panelist. All suggested that their organizations had successfully pivoted from survival mode toward a rebirth of sorts, devising creative ways to connect with their audiences—and with their peers.

Ramirez said that The Music Center’s efforts to find innovative ways to offer virtual performances, such as turning traditional live summer dance events into online dance-teaching sessions, gave the organization a way to provide useful content to audiences while keeping the dancers employed, an important institutional objective. It has also led to a greater degree of internal communication and collaboration among staff members at The Music Center, which houses four resident companies and produces a variety of performances and educational experiences. In a follow-up conversation, Ramirez said it was essential for staff members to become “unstuck” and break free of their tried and true ways of preparing performances to better respond to, engage with and build audiences during the shutdown. This often involved tweaking some job responsibilities.

“Everyone had to learn something new and different,” she said. “Under those circumstances, we had to communicate more than ever with staff, to make explicit all the things they needed to do that before were always implicit. We’d never had to do that before. Now we had to communicate more and better on what was expected and new methods. Old expectations were exploded. We had to help people get comfortable with constant change and that meant a lot more and better communication.”

Massbach said that the Museum of Chinese in America had benefited too from new levels of staff inclusiveness and brainstorming, which has produced innovations such as using the museum’s street-facing windows for exhibits, something not done previously. The organization has also revamped its website to more effectively promote the museum’s recent initiatives, including its response to anti-Asian attacks, the launch of a series how to be an ally and presentations on unsung aspects of the Chinese diaspora in the United States.

It Takes a Village

Another key to building audiences and strengthening arts organizations overall has been to seek out greater collaboration within the arts and cultural sector. That has included ideas such as sharing useful information and replacing competition for grant dollars with cooperation, i.e., having nonprofits, particularly those operating within the same racial or cultural communities, jointly apply for—and then share—funding.

To accomplish that, Massbach suggested that funders consider providing grants to what she called a BIPOC “fund of funds,” adapted from a model used in the financial sector—creating an umbrella organization that could collect grants and funds and then allocate the money more equitably among multiple organizations in a particular community.

“If you have, hypothetically, a thousand small cultural organizations applying for money, and foundations are trying to discern between a thousand, it’s really, really hard,” she said. She went on to elaborate during the panel discussion that if a group of organizations could create that “fund of funds,” or “foundation of foundations,” to guide money toward many different organizations, the money could be distributed more equitably and sustainably. “I don’t want to be the ‘check the box’ Chinese-American organization that gets the funding when other people don’t because it was easier for people to do that work,” she said.

In another example of field collaboration, Glass said that she has benefited from a spontaneously created forum for New York-based arts and cultural organizations to meet, share ideas and collaborate on advocacy. Launched in March 2020, the virtual meetings were dubbed Culture@3 for their start time. “For the first few meetings we talked about things like how to get hand sanitizer,” Glass said. “Then we started discussing whatever problems came up, things like insurance problems and city funding. It turned into a place of advocacy and support, sharing information. For this field to survive we need to keep these lines of communication open.”

Lucy Sexton, the executive director of New Yorkers for Culture & Arts, an advocacy group, and one of three people who help run Culture@3, said the effort was having a big impact on the hundreds of organizations that have become regular participants. While meetings were initially held seven days a week, given the enormous need early in the shutdown, they are now on a four-day-a-week schedule. In addition to running the general meetings, the organizers have spun off working groups on such topics as fundraising and human resources. Recently, Sexton said, the group brought in an expert to explain changes in the tax rules for unemployment benefits, and one of their working groups raised $150,000 to provide emergency grants, as much as $500, to artists in need.

“This has helped us build stronger advocacy for the cultural field,” Sexton said. “We never talked like this before. There was no collaboration, no communication like this.”

Glass added that her hope was that this collaboration might prevent the sort of panic she recalls experiencing when the shutdown first hit. The sense of helplessness and being caught completely off guard without a viable game plan is something she says she wants to avoid in the future.

“That’s what’s making me look hard at our business model,” Glass said. “I don’t want us to hit the next catastrophe, and there will be a next one at some point, and I’m curled up in a ball unprepared. Before that catastrophe we need to create a system for when the Bat-Signal goes up, everyone knows what their role is and how to respond.”

Ramirez agreed and said that, while arts organizations always need to remain focused on financial sustainability, one of the lessons of the pandemic is that opportunities to bring in larger, more diverse audiences should be pursued even if there is no immediate financial return. “For us, it’s about expanding our family, for people to understand who we are and to experience our work,” she said. “It’s really about the expansion of our family more than anything else.”

Stories from Reimagining the Future of the Arts