At the end of the school day, few teachers would find it easy to engage students in a complex lesson in the arts—or any other subject. But early on a recent evening in Dallas, the subject was hip-hop and the cross-cultural influences that shaped it. The setting was a mirrored dance studio at a recreation center in a neighborhood made up largely of Spanish-speakers and African-Americans. And the challenge of engaging 12 boys and girls aged 6 to 16 was being met masterfully by a lanky, 50-something musician and teacher named Leo Hassan, the product of a path-breaking, citywide arts education effort known as Thriving Minds.[fn value=1]Previously known as the Dallas Arts Learning Initiative (DALI) the effort was renamed Thriving Minds in July 2008.[/fn]

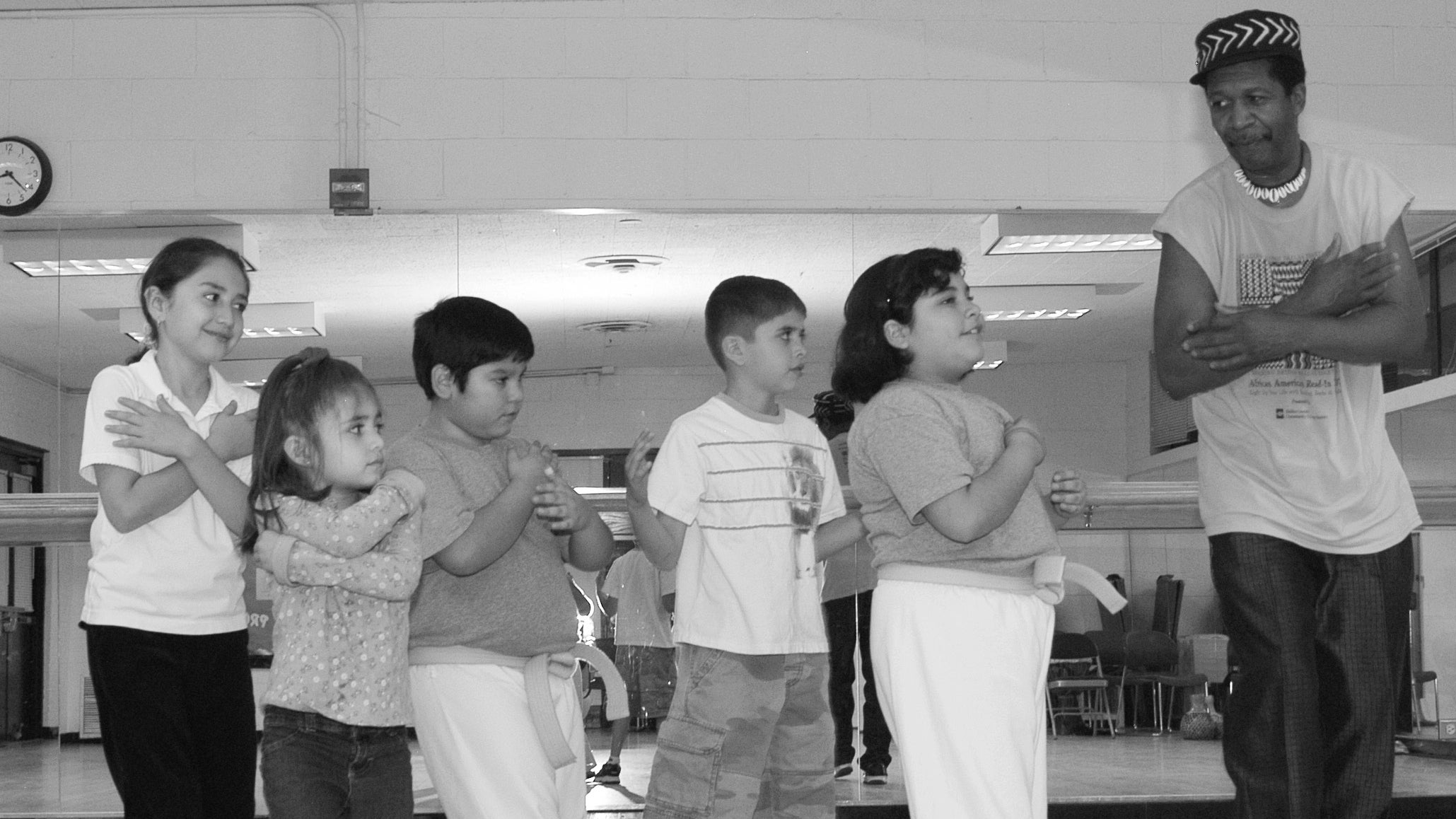

The students seated themselves in a semi-circle around Hassan, who says he fell in love with the art of hip-hop during its early years and wants to rescue it from the “mean behavior and bad lyrics” that many children find in it today. After equipping each member of the class with “djembes,” hand-drums from West Africa, and other percussion instruments, Hassan launched into a hands-on music history lesson that traced hip-hop’s ancestry through Africa, the Caribbean and the streets of New York. Then, Hassan collected the instruments and had his students apply their newly learned rhythms to movement, stepping and sweating the class through an hour-and-a-half of increasingly intricate dance routines. He mock-barked orders, “C’mon, work it!” He lavished praise, “Yes! Thank you!” And by the end of this out-of-school class two hours after it had begun, his students had received a physical, musical and intellectual workout, learning the basics of a popular art form and how it came to be.

Hassan, who draws on his skills as an Afro-Latin percussionist and former youth social worker, is known in the Dallas arts education community as a stand-out teacher, but his rec center Hip-Hop for Kids course is unusual in another way, too. It is the result of Thriving Minds’ nationally recognized work to link artists, local government, cultural organizations, schools, parents, and anyone else who can be enlisted to bring arts education to Dallas’ children, especially the poorest, both during and after school. With the support of The Wallace Foundation, Thriving Minds has succeeded in more than doubling the number of arts teachers in Dallas public elementary schools and supplying them with equipment and training. It has launched a summer arts program that reached 3,500 children last year. It has undertaken research to help increase the amount and quality of arts experiences for children. And it has made available a host of new, neighborhood out-of-school time arts activities for kids, from hip-hop to Shakespearean drama.

This is no mean feat at a time when arts education, a given in most affluent school districts, has seriously eroded in the public schools of many American cities. “We have a social justice agenda,” says Gigi Antoni, the moving force behind Thriving Minds and the head of Big Thought, the Dallas arts education group that manages the initiative. “It’s about equity. The arts should be for every kid.”

Coordinated initiatives for arts education: An emerging trend

Thriving Minds is perhaps the most striking example of a relatively new phenomenon in a number of urban areas today: “coordinated arts learning efforts,” as a report from the RAND Corporation calls them, to expand and improve arts education for children who now receive little of it. The report, Revitalizing Arts Education Through Community-Wide Coordination, was commissioned by The Wallace Foundation and examines six U.S. cities and counties where such initiatives have emerged with differing degrees of success over the last decade: Alameda County in northern California, Boston, Chicago, Dallas, Los Angeles County and New York City.

The efforts are springing up in these and other cities for a combination of reasons. The first is, simply, a conviction that when young people experience the arts, they benefit in many ways. As detailed in another RAND study, Gifts of the Muse, arts participation can offer pleasure and satisfaction, expand people’s intellectual growth and feelings of empathy for others, and foster a deeper sense of community, for starters. And as the study puts it: “Early exposure is often key to developing life-long involvement in the arts.” In other words, children who experience and learn about the arts are far likelier to enjoy them and reap arts’ benefits as adults.

The trend toward more coordinated actions in arts learning in some cities is also a response to the dramatic decline in urban public-school arts instruction that began in the 1970s, when states and cities began to pare back funding for education, cutting in particular the arts and other “non-core” subjects. Many observers also believe that arts education has been further weakened by the emphasis, reinforced by the 2001 federal No Child Left Behind law, on standardized tests in reading and mathematics.

Over the years, a number of institutions have sought to help fill the arts education gap. Museums and other cultural organizations expanded their education initiatives, while philanthropies directed more funding to children’s arts programming, according to the RAND Revitalizing study. Many out-of-school time programs that grew with the large-scale entry of women into the workforce beginning in the 1970s opened up new venues for arts learning. And not-for-profit organizations whose specific aim was to promote arts experiences in the schools—such as ArtsConnection in New York City and the Chicago Arts Partnerships in Education—emerged nationwide to supply everything from programs that paired professional artists with classrooms to programs that trained non-arts teachers about art concepts they could incorporate into their instruction.

This increase in the number and type of sources for arts education, coupled with the desire to fill the arts void in schools, led to efforts to lend a semblance of coherence to the offerings and lift their quality. Thus about a decade ago “coordinated initiatives” appeared, tapping the new collection of arts-education groups and other institutions for concerted action. For Michael Hinojosa, superintendent of the Dallas Independent School District, the reintroduction of arts to his city’s children today would not have occurred without such an effort in Dallas. “Someone had to be the champion to pull it all together,” he says.

Shaped by local circumstances, each initiative examined by RAND has approached the task of reinvigorating arts learning differently, although most have focused on increasing arts education in public schools. While such efforts are promising, however, they are also fragile, as the RAND study emphasizes. Coordinated efforts are subject to many forces over which their supporters have little or no control, from changes in education policies to the precariousness of funding. Success also demands sure and steady leadership as well as the diplomatic savvy necessary to unite multiple organizations with competing interests, goals and ways of doing business. Beyond that is the immensity of the problem the efforts seek to solve. Indeed, in Dallas an entire generation went by before the city began to bring the number of arts teachers in its elementary schools back to 1978 levels—a task that won’t be completed until later in 2008.

Thriving minds: A Three-part Effort With a 20-year history

The coordinated efforts that RAND studied required patience, persistence—and years to develop. Thriving Minds’ roots go back to the early 1980s when arts advocates formed the Partnership for Arts, Culture and Education (PACE), a group to press city movers-and-shakers for more arts in the schools. By the early 1990s, PACE was finding common cause with new groups offering arts programming to children.

Prominent among them was Big Thought’s predecessor, Young Audiences of North Texas which, like its national parent organization, brought teaching artists into classrooms. Gradually, Young Audiences also developed a variety of other arts-learning programs for children and teenagers, including one focused on juvenile offenders and another based in public libraries. Thus, while PACE worked to urge policymakers to improve arts education, Young Audiences expanded its arts programming reach, Antoni recalls. Their efforts reached a turning point in 1998, when the city’s Office of Cultural Affairs and the Dallas Independent School District inaugurated what would evolve over the next decade into a three-pronged endeavor managed by Young Audiences (later renamed Big Thought): promoting “arts integration” by using arts and culture to help teach core subjects in schools; reintroducing formal arts instruction in elementary schools; and organizing communities to seek out and develop neighborhood arts programming for young people.

Arts Integration

The arts integration program, called Dallas ArtsPartners, began in 1998 as a pilot in 13 Dallas elementary schools. In 2002, after a school district study showed that participating children fared better on reading and math tests than comparable non-participants, school officials expanded it so that today it is accessible to all 88,000 Dallas elementary school students. Big Thought operates as a kind of broker in ArtsPartners, promoting to schools a variety of cultural programs prepared by some 57 different cultural institutions—from the Dallas Museum of Art to the Texana Living History Association. Many programs feature museum visits or live performances, but each offering is intended to solidify teaching of the schools’ mandated curriculum, and Big Thought has instituted a number of measures to make sure the programs are educationally sound. One is to provide arts-integration training for both teachers and the cultural organizations. Another is to offer classroom teachers close to 60 program-related curricula, complete with sample lessons, that have been prepared by teachers and vetted by a panel of educators and cultural mavens.

Instruction in Arts Disciplines

Its emphasis on quality and coordination with classroom needs earned Big Thought necessary credibility across the city’s arts and education establishments, a factor that helped usher in the second prong of Thriving Minds’ strategy—increasing arts instruction in its own right. Two years ago, Dallas school officials announced that the district would begin hiring 140 new arts teachers so that by the 2008-2009 school year every elementary school student in the city would be receiving 45 minutes each of visual arts and music instruction weekly. Wallace’s support for development of efforts to improve and expand city arts learning was one important catalyst for the increased arts instruction. But there were others, too, according to Antoni. For one thing, Big Thought found an important ally in 2005 with the appointment as superintendent of Hinojosa, a passionate arts education advocate who says both personal experiences and professional experience in school districts with strong arts programs have convinced him of the power of arts education. For another, Big Thought representatives, taking on the role of advocates in addition to programmers after PACE disbanded in the late 1990s, had laid the intellectual groundwork for the revitalization of arts instruction, arguing for years to policymakers that arts integration was an important teaching tool but no substitute for what RAND calls “discipline-based stand-alone” arts education.

In pushing for the reintroduction of high quality arts education for children, Big Thought did more than talk. Thriving Minds funds have paid for a scheduled overhaul of the city’s K-12 arts curriculum in exchange for the school district’s agreement to begin it at once instead of in 2010 as originally planned. Thriving Minds funding has also supported the purchase of classroom musical instruments and training for music teachers in a respected method of instruction developed by the German composer Carl Orff. One beneficiary, Mariano Aguirre, a young music teacher at Maple Lawn Elementary School, says he first realized the power of Thriving Minds’ efforts when his second graders successfully performed a five-part composition. “I had all these kids going, everyone keeping the same time,” he recalls. “It made me really realize what these kids could do.”

“Creative Communities”

The third and newest part of the Thriving Minds strategy, formally launched in the summer of 2007, aims to make the arts a vital part of out-of-school time and other neighborhood programs. Called “creative communities,” the project is now being rolled out in five neighborhoods. It brings together librarians, parks and recreation managers, school representatives, youth and cultural programmers, parents, church workers and other community figures to assess neighborhood needs and resources, determine which arts programming would be beneficial to their kids, and develop plans to get the programming. Three city agencies—cultural affairs, parks and recreation, and libraries, along with the Dallas Independent School District—are working on the project with Big Thought, which has paired each neighborhood with a Thriving Minds representative who gets to know the area well enough to help the local leaders develop youth arts activities in sync with neighborhood desires.

Hassan’s hip-hop class, one of a number of Thriving Minds-supported arts offerings new to the Far East section of Dallas, for example, came about after Thriving Minds representative Nikki Young discovered that a city-run recreation center there needed additional activities for an all-day summer camp as well as more school-year activities that appealed to young teens. The Thriving Minds-funded programs provided to the Harry Stone Recreation Center—from photography to hat-making—have given it a sorely-needed alternative to sports to engage children, according to Brenda Sanders, the center’s community program manager and a member of the neighborhood leadership team for Far East Dallas. “Arts are basic for children in terms of learning, creativity and growth,” she says. “If they can allow themselves to dream and hope, they’ll do better in the other aspects of their lives.”

The strategies employed

In one way, Dallas would seem an unlikely home for a renaissance in arts education. Texas was a cradle of the national movement to induce school reform through more high-stakes testing, a move that helped push non-tested subjects such as arts to the periphery of the curriculum. But like the other cities RAND surveyed, Dallas benefits from a vibrant cultural community, one that in 2009 is scheduled to unveil a showcase, multi-building performing arts center.

A climate receptive to the arts was only one factor in the development of Thriving Minds, however, and the RAND study lists several common strategies that the initiatives it examined employed to expand arts education. One was to document the scarcity and uneven distribution of arts education in city public schools and then use the information to press decisionmakers for more equity—with the eventual goal of arts education for all. Another was to push for the creation of a highly placed arts education coordinator within the school bureaucracy—a step considered so important in Chicago, for example, that private philanthropy initially paid half of the salary for the new post there. Attracting and making innovative use of funding, careful planning, and engaging in effective advocacy were other common activities in cities pursuing coordinated arts learning efforts. The sites examined by RAND also worked to improve the quality of arts education, adopting strategies that included training teachers or other “capacity building” measures, and ensuring that cultural programming for students stood on educationally solid ground.

The RAND study found, in addition, that certain conditions nurtured the efforts. Seed money was one important factor; in Dallas, for example, early support from prominent national sources, including the National Endowment for the Arts and the Ford Foundation, offered Big Thought needed funding as well as a measure of prestige that boosted fundraising from local sources.

Strong leadership, which often came from outside the school district and could take on challenges such as reconciling differences in the sometimes fractious arts education community, was another crucial factor. A leader of Los Angeles County’s Arts for All initiative, for example, described for RAND “a key moment” when two groups often at odds—supporters of “arts integration” and advocates of stand-alone instruction—decided LA schools should have a place for both, “so everyone stopped fighting.”

Key strategies Dallas has used to reinforce its coordinated approach to arts learning include:

- Surveying the arts education landscape

At the request of Dallas’s cultural commission in 1997, Big Thought agreed to study how effectively the city’s cultural institutions’ education outreach efforts, many of which were subsidized by tax dollars, reached the city’s children. The key finding struck a nerve: only an estimated one-quarter of the city’s school children benefited from cultural programming, and affluent children generally had multiple arts experiences while other children had few or none. “This city is so rich in its cultural and arts organizations, and what they have to offer, that the fact there were kids being left out spoke to me,” says Eli Mercado, a member of Big Thought’s board of directors. Armed with the data from the study, arts education advocates were able to press for change, and this led to the establishment of ArtsPartners and its eventual spread to all city schools.

- Leadership through collaboration

Another strategy Big Thought adopted was leadership shaped by consensus. For many cultural institutions, the study that revealed citywide disparities in arts learning experiences prompted fears that scarce cultural dollars might be shifted away from the arts and into education, recalls Antoni, Big Thought’s veteran president and CEO. To allay these concerns and keep the city’s cultural community on Big Thought’s side in working to improve arts education, Antoni and others made a critically important fundraising decision: money for arts education from the city, foundations, corporations and individuals had to be “new,” that is, it could not come at the expense of current support for arts organizations.

Such coalition-building paid off. ArtsPartners has been governed and shaped over the years by representatives of all its constituent parts, including artists, teachers, city council members, school officials and arts organizations. Funding and support for the program comes from the school district, the city and Big Thought, through private contributors.

- Research to assess effectiveness

Big Thought has embraced assessment of its work, both because the education climate in which it has operated over the years demands evidence of results and because assessment has proved to be a vital tool in self-improvement. After the early evaluation of ArtsPartners by the school district, Big Thought embarked on a second, three-year longitudinal study,[fn value=2]See: Dennis Palmer Wolf, Jennifer Branson, Katy Denson, More than Measuring: Program Evaluation as an Opportunity to Build the Capacity of Communities, Big Thought, 2007.[/fn] headed by a leading researcher from the Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University. The idea was not only to document the educational benefits of ArtsPartners, but also to improve the program. The study discovered, for example, that one seemingly solid arts integration lesson that revolved around having second-graders attend a play and listen to a storyteller was ineffective, perhaps because its purpose—teaching about idiomatic expressions—was too narrow. On the other hand, the study found that strong ArtsPartners programming could boost children’s ability to develop “voice” in their writing. “We do research for accountability reasons, and that is very important,” says Jennifer Bransom, Big Thought’s research director. “But we also do it to learn. … Accountability fuels our knowledge of how we can make our programs better.”

Big Thought also turns to research to inform the design of its major initiatives. The launch of creative communities, for example, was preceded by a year of study and planning that included surveys and focus groups of students, families and community leaders. One discovery was that parents and children are involved in numerous creative endeavors that qualify as what Big Thought manager Erin Offord calls “little ‘a’ art,” such as sewing or cooking. The finding, which has led to the introduction of neighborhood classes in everything from gardening to cake decorating, has given organizers a new way to engage families that might otherwise feel unwelcome in the world of arts. Big Thought has also launched a three-year study to follow families to determine whether the creative communities program is working and how it might best be enhanced.

- Advocacy for sustainability

Finding allies at the apex of civic leadership has been essential to Big Thought’s growth, but the effort’s leaders also realized early on that they would have to cultivate other advocates within city agencies and organizations if the initiative were to last. “The idea is that we work with a multitude of people at the upper levels of organizations, not only the top,” says Gina Thorsen, vice president of Big Thought. One result is that many layers of the city’s political and institutional bureaucracies are now seeded with Big Thought advocates, a way of ensuring sustainability. These advocates include Mary Suhm, a Dallas city government veteran and longtime ArtsPartners supporter who in 2005 was named Dallas city manager, the top non-elected post in the municipality. “Better students, better workforce, better tax-base,” she replies when asked why she favors arts education.

The Coordinated Approach: Challenges and Promise

None of this suggests guaranteed success for Thriving Minds. Indeed, challenges come from many directions, underscoring RAND’s finding that success in citywide coordinated approaches to arts learning can be fragile. Raising and sustaining adequate funding is one concern for Antoni. For its first three years (2007, 2008 and 2009), Thriving Minds is expected to cost about $40 million, with about $17 million from private sources and the rest largely from the schools (for the arts teacher salaries, for example) and the city (for contributions from parks and other agencies). So far, Big Thought has raised all but $800,000 of that $17 million, having secured funds from corporations, individuals, and local and national foundations, including Wallace. Still, for the long-term, the group must build up its endowment, Antoni says, and although she believes careful planning and multi-year financial commitments from public and private organizations go a long way to mitigate risk, she is keenly aware of the consequences if key funding from the city or other sources decreases or disappears.

Another concern is the possibility of abrupt changes in leadership or policy. Before Hinojosa’s 2005 appointment, the city had gone through seven school superintendents and interim appointees in 10 years. After an election last year, the 14-member Dallas City Council lost half of its incumbents, meaning that new members whose views on the arts were largely unknown would be pivotal in deter-mining the fate of a crucial proposed $830,000 appropriation for Thriving Minds. In response, Big Thought had to mobilize an intense and ultimately successful contact-your-legislator campaign.

Even when leadership and policy are friendly to the arts, strong countervailing forces can work against arts learning efforts. Feeling resistance from principals who preferred to use arts instruction time for test prep or other purposes, school district officials earlier this year issued a directive making clear that students could not be pulled from visual art or music classes for tutoring—or anything else. “The vast majority of principals understand the value of arts education for kids and they are all for it,” says Craig Welle, who, as executive director of enrichment curriculum and instruction, oversees arts education in the school district. “But there are always a few who don’t get it.”

Whatever the difficulties, Thriving Minds is, for now, making itself felt in the lives of children who otherwise would have little access to the arts. One of them is a soft-spoken 13-year-old named Lonniesha Mitchell, who attended summer camp last year at the New Hope Community Center, which is based in a church in a transitional part of Far East Dallas and run by Lutheran urban missionaries. Recently Lonniesha recalled how learning photography in a Thriving Minds class there had sparked a new interest for her. She said she hoped to attend a high school where she could learn more about art and perhaps, one day, become a professional photographer.

What did she like so much about photography, a visitor asked her. That it gave her the chance to focus deeply on something that would come out well, Lonniesha answered. That it provided an outlet when she felt frustrated. That it taught her to perform tasks with care and to discover that there were many different ways to view the same object. Stopping for a moment, she mimicked the motion of holding up a camera to her forehead. “You close your eyes,” she said, “and imagine.”

Wallace’s Work in the Arts:

The Wallace Foundation’s long legacy of support for building arts participation has its roots in the words of its co-founder, Lila Acheson Wallace, who said “the arts belong to everyone.” Our current goal in the arts is to build current and future audiences by making the arts a part of more people’s lives. To help achieve that, our strategy has two components:

- the Wallace Excellence Awards, which provide support to exemplary arts organizations in selected

cities to identify, develop and share effective ideas and practices to reach more people; and

- Arts for Young People, whose goal is to help selected cities develop effective approaches for expanding high-quality arts learning opportunities both inside and outside of school, and to capture and share lessons that can benefit many other cities and arts organizations.

At present, Dallas is the sole site receiving Wallace support for an arts learning initiative, having developed strong plans for implementation and having a range of criteria for likely success including: an actively involved school district, the presence and active commitment of providers of high-quality arts education, and an organization (Big Thought) capable of bringing together the school district and the arts organizations so that the needs of many more young people are met.

This report on Dallas’s efforts in arts learning reflects the collective contributions and thinking of Wallace’s arts program, research and communications staff and was written by Wallace Senior Writer Pamela Mendels.

Related Wallace Products:

To learn more about arts learning and related topics, the following can be downloaded for free from The Wallace Foundation’s website at www.wallacefoundation.org:

Revitalizing Arts Education through Community-Wide Coordination, RAND Corporation, 2008

The Arts and State Government: At Arm’s Length or Arm-in-Arm?, RAND Corporation, 2006

Motivations Matter: Findings and Practical Implications of a National Survey of Cultural Participation, The Urban Institute, 2005