So you want to start an afterschool program or expand the one you’ve got. You have demand in your community and an idea of what kinds of activities you want to offer. You even have a space lined up. What you need now is funding. The good news is that the federal government makes money available for afterschool under a number of funding streams in the 2015 Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), particularly through the 21st Century Community Learning Centers program. (President Trump’s latest budget proposal would do away with 21st Century funding in the 2020 fiscal year, but the program has survived other recent efforts at elimination.) In order to be eligible for that money, however, you may need something else: strong, research-based evidence that your program can be effective in improving outcomes for young people.

Fortunately, there’s a body of evidence about the effectiveness of afterschool programs already out there. To help providers tap into that research, Wallace commissioned a report from Research for Action, an independent organization with a focus on education. The report reviews virtually all the available studies of afterschool programs from 2000 to 2017 and identifies those programs that meet ESSA requirements for credible evidence. Research for Action found more than 60 programs—covering all grade levels and almost every type of program—that fall into the top three of four levels of evidence described in ESSA. The report is accompanied by a guide that provides details about each program and summaries of the studies included in the review.

We talked to Ruth Neild, the report’s lead author and recently-named president of the Society for Research on Education Effectiveness, about why afterschool should be more than an afterthought and how providers and policymakers can use her work to create programs that make a difference for students.*

We talked to Ruth Neild, the report’s lead author and recently-named president of the Society for Research on Education Effectiveness, about why afterschool should be more than an afterthought and how providers and policymakers can use her work to create programs that make a difference for students.*

What is the need that this report and companion guide are intended to fill?

ESSA encourages, and, in some cases, requires, providers and districts to use evidence-based practices, and it has specific standards for different levels of evidence. This raises a question: Folks in the afterschool space and the district aren’t researchers, so how in the world are they going to know what the evidence is? How are they even going to access it since a lot of it is behind paywalls? Our contribution to the field is that we’re bringing that evidence out into the open for everyone to take a look at. We did a comprehensive scan of the literature on every afterschool program we could find and reviewed it against the ESSA standards, so districts and providers don’t have to do that for themselves.

Why does afterschool programming matter for young people?

Afterschool programming obviously has the potential, at minimum, to keep students safe and supervised. It also has the potential to help students keep pace academically. A lot of programs, for example, include tutoring and academic enrichment. Beyond that, it has the potential to provide enrichment, including interest exploration and physical activity, that complements the school day and, in some cases, may not be available during the school day. Examples of that include arts, apprenticeships, internships, and self-directed science activities like robotics. In addition to standards of evidence, ESSA talks about a “well-rounded education.” Afterschool can help with that.

What are the headlines from your review of the available evidence on the effectiveness of afterschool programs?

One of the important things this review shows is that, when you do a comprehensive search and assessment of the most rigorous evidence, you find there are many programs that have positive effects and that, taken together, these programs have positive effects on a range of outcomes, whether you’re talking academics, physical health, attendance, or promotion and graduation. I think that is news, actually. There have been questions in the past based on a small handful of studies about whether there are net benefits of afterschool programs. But when you do a comprehensive search and you pull all the studies together and look at the average effects, for most outcomes the average effects are positive, and there are plenty of programs that have had positive impacts on students.

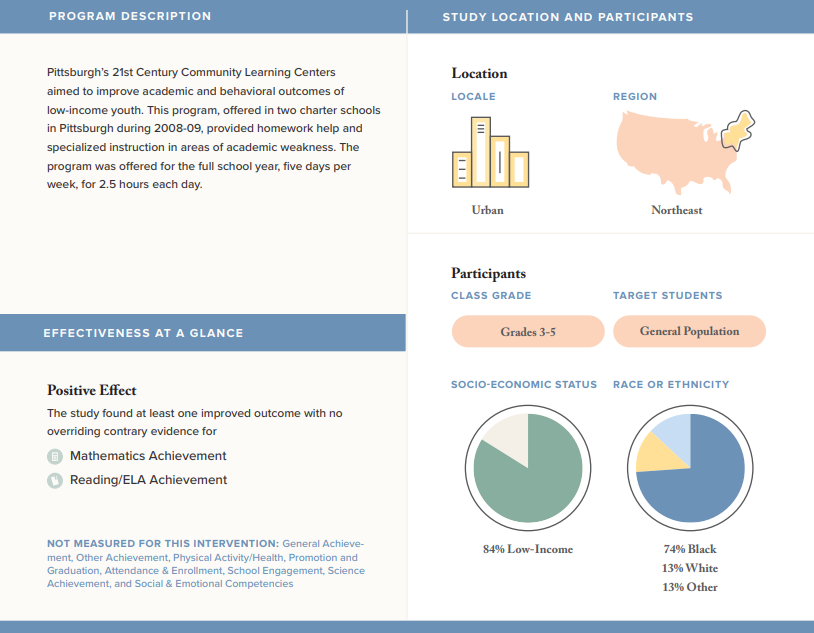

The report's companion guide provides summaries, such as this one, on the research about the effectiveness of specific afterschool programs.

How can program providers use the report and guide in their decision-making?

For providers, we summarize both branded and unbranded programs. Branded programs are formally organized and have a formal model. They may have a manual and a name. Some afterschool programs are branded, but probably most of them are homegrown models. For providers who might be thinking about purchasing products from the branded programs, the guide is a place to go and check a summary of their evidence. For providers who are developing a homegrown model, looking to see what others have done is a way of doing a tune-up on your own offerings. It helps you to think, “Here’s what I’m offering. What might I be able to expect in terms of outcomes for my kids?”

What advice do you have for a provider who may be seeking federal funding for a program that doesn’t already have established evidence of effectiveness?

First of all, in the afterschool context, a lot is left to the states to determine, so it’s important to know what level of evidence your state is requiring. Another thing providers should do is look in the guide to see if there is a program with important similarities to the one they’re offering that’s been shown to have a positive impact. When you’re putting in evidence to apply for federal funding, that evidence doesn’t haven’t to be from your particular program; it could be from a like program.

Another important thing to know is that Tier 4 [the fourth level of evidence described in ESSA], offers a door through which a program can be offered, as long as there’s a compelling research-informed argument for why the program would have an impact and it’s being studied for effectiveness. Our review highlights some areas evaluators and programs should keep in mind as they’re figuring out what their evaluations should look like. For example, it’s important to think about getting a large enough sample size, otherwise your program is going to appear to have no statistically significant effects—even if it’s actually effective.

The afterschool field should also be thinking about what kind and intensity of outcomes afterschool programs can realistically produce. We found an awful lot of programs that use standardized test scores as an outcome. Test scores are easily available from school records. The problem is they’re very hard to budge. Think about school improvement grants: Millions and millions of dollars went into intensive school-day interventions, and it was hard to get a bang out of that. It seems potentially harmful to hold afterschool programs to that standard. The amazing thing is that afterschool programs have done it, but we would encourage providers and funders to think hard about whether there are other meaningful measures that can be used to capture what these programs are trying to change. Sometimes, funders may need to help providers develop those measures.

What lessons does your review of the evidence base hold for state and federal policymakers? What can they do to promote effective afterschool programming?

Providers, districts, and schools can be lauded: Great job. You’ve shown that afterschool programs can be evaluated in rigorous ways and have some positive outcomes. Where the field needs to go next is to conduct better studies that test particular approaches, not just a mishmash of different approaches and outcomes. For example, if you’re going to have a program that’s trying to affect academic outcomes, really take a look at what it takes. How much time does it take? Can you offer it two days a week or do you need to offer it five days a week? What kind of staffing do you need to have? Are there requirements or incentives for participation you need to have?

States are in a great position to incentivize or require providers to develop a learning agenda because they’re re-granting a billion dollars collectively through the 21st Century Community Learning Centers. There is evaluation money built into that program. But I don’t see great examples of states developing clear learning agendas with their grantees. That seems like the next step to me.

*This interview has been edited and condensed.