Higher Achievement provides intensive beyond-the-school-day study and enrichment to middle school kids in underserved communities. The Campus Kitchens Project serves up nutritious meals to the hungry. And Climate Matters distributes free, research-based videos about climate change to TV weathercasts.

Three social programs with three different missions—and an intriguing commonality. Each one has successfully widened its reach in recent years by working in partnership with others, albeit in varied ways.

The three are among 45 nonprofits showcased in a recent report on expansion via partnership. In Strategies to Scale Up Social Programs: Pathways, Partnerships and Fidelity, authors R. Sam Larson, James W. Dearing and Thomas E. Backer explore this terrain, examining such matters as how partners find one another and the extent to which program creators demand “fidelity,” or faithfulness to the original programming model, vs. valuing adaptation.

As a foundation whose work involves testing possible solutions to problems in our focus areas (school leadership, the arts, and learning and enrichment for disadvantaged children), Wallace commissioned the report in part to find out more about how successful nonprofit efforts could expand. Several of the organizations studied in the report, including Higher Achievement, have been Wallace grantees.

To be included in the write-up, all the efforts had to have evidence of effectiveness and fall into one of three areas: health, education and youth development. The range of enterprises, however, is wide—from prenatal care for low-income women (Nurse-Family Partnership) to summer learning (Power Scholars Academy, another Wallace-supported endeavor) to business education for entrepreneurs in underserved areas (Streetwise MBA).

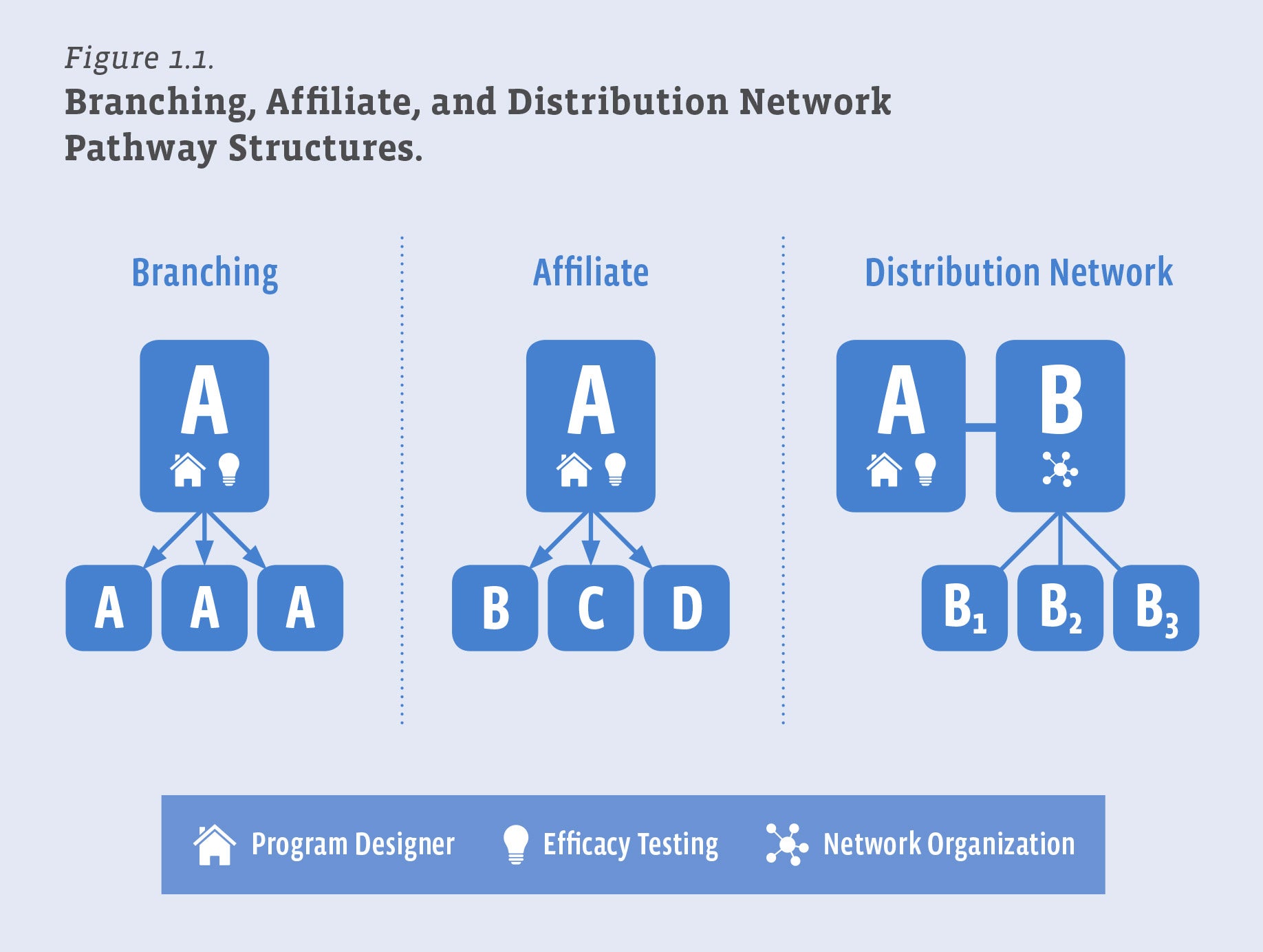

Whatever their mission, each of the 45 faced a fundamental question before scaling up via partnership: What was the best course to take? In short, the report found three common partnership paths.

Branching pathways are similar to a business setting up branch offices. The lead partner (the group organizing the scale-up and usually the program creator) opens more sites, with the training and supports of the original. This was the route taken by Higher Achievement, which today works in 17 schools in four cities to provide both school-year and summer supports to put middle school students on a course to success in high school and college.

Like many organizations in the study that took the branching path, Higher Achievement, founded in Washington, D.C., in the 1970s, was well established when it began considering expansion. It opened its first branch in 2009 in Baltimore, later adding Richmond and Pittsburgh—and gathering lessons along the way on everything from how to enlist funders to how to time hiring, according to Lynsey Wood Jeffries, Higher Achievement’s CEO. The partner in each city is a local office established by Higher Achievement. These branches are given flexibility in certain areas, such as the types of elective activities they can offer to the children. But they are expected to adhere strictly to a set of program non-negotiables, such as academic mentoring, as well as the rigor of the program model, which provides on the order of 100 extra school days of learning and enrichment annually to the 1,900 students enrolled.

Indeed, Higher Achievement chose the branching pathway because the level of control it provides helps to ensure maintenance of the program’s intensity, which the organization considers key to good results for the students. “We couldn’t rely on a less centrally controlled approach to scaling and feel confident that we would produce strong outcomes,” Jeffries says.- Affiliate pathways resemble business franchising. Here, the lead partner retains basics—name, content and quality control, for example—but the affiliates are independent, often operating under contracts with the lead partner.

That’s how Campus Kitchens operates. Launched in 2001 and originated by DC Central Kitchen, which combats hunger in the nation’s capital, The Campus Kitchens Project has since spread to 63 schools, mostly colleges and universities, in 63 communities, according to Dan Abrams, director of the effort.

The heart of the program is that students recover would-be wasted foods, usually from their own dining halls, transform them into tasty, healthy meals, and deliver them to places such as senior housing, churches and youth outreach groups. In addition, each site provides “Beyond the Meal” programming that goes beyond immediate hunger relief and could include health education, community gardens and mobile food pantries, Abrams said. The particulars are tailored to each community.

Partnerships are central to the enterprise. Sodexo Corp., a corporate food service operator on many campuses, helped develop strategies for keeping both food and students safe in the kitchen. AARP funded a report of case studies on Beyond the Meal ideas that help address hunger and poverty for older adults and is available online free to students.

“Our goal is to provide the most cost-efficient and effective program for students to take on,” Abrams said.

- The distribution network pathway is akin to supply chain business arrangements, where the lead partner provides the content (the “product”) and a partner with an existing network distributes it to member organizations or individuals. Case in point: Climate Matters, which is based at George Mason University in Northern Virginia and was begun, with the help of a National Science Foundation grant, as a pilot test in 2010 with one weathercaster. Today some 500 TV weathercasters participate, which means the effort reaches 147 of the nation’s 210 media markets. The weathercasters receive a weekly “story package" of broadcast-ready graphics or animations plus background information, often featuring data localized to their media market, that illustrate a current impact of climate change.

Edward Maibach, who was in on Climate Matters’ origins, is director of the university’s Center for Climate Change Communication. He describes the partnership driving Climate Matters as “a team effort between three kinds of experts …climate scientists (so we get the facts right), social scientists (so we communicate the facts effectively), and TV weathercasters (who are trusted, have access to the public, and are excellent science communicators).” In the future, other partners may join in. Maibach says Climate Matters is working with a diverse group of journalism professional societies to see how Climate Matters materials might help local journalists report on the impact of climate change, and potential solutions, in their community.

The search for ways to expand that make sense for an organization’s particular context drives home another key point of the report—that scale-up is often not a one-time event. Those doing the work need to constantly re-evaluate pathways, partnerships and fidelity Higher Achievement, for example, has a small pilot underway to test the types of outcomes that a tweaked program model, spread through a distribution network pathway, would have, Jeffries says. Dynamic change,” the authors write, “is a reality for successful social programs to scale up.”