Over the past two decades, we at Wallace have learned a lot about how afterschool systems work and how cities can go about building them. One thing we still didn’t know, however, was whether cities would be able to sustain their efforts to coordinate the work of out-of-school-time providers, government agencies and others over a period of years. Now, a new report by the nonprofit human development organization FHI 360 offers some answers.

Stability and Change in Afterschool Systems, 2013-2020 is a follow-up to an earlier study of 100 large U.S. cities, of which 77 were found to be engaged in some aspects of afterschool coordination. For the current report, the authors were able to contact 67 of those 77 cities. They also followed up with 50 cities that weren’t coordinating afterschool programs in 2013 and found a knowledgeable contact in 34 of them.

The report provides a snapshot of the state of afterschool coordination just before COVID-19 hit, causing the devastating closure of schools and afterschool programs. We recently had an email exchange with the lead authors, Ivan Charner, formerly of FHI 360 and Linda Simkin, senior consultant on the project, about what they found in their research and what the implications might be for cities looking to restore their afterschool services in the wake of the pandemic. Their responses have been edited for length and clarity.

What do you consider the key findings of this research?

We discovered that more than three-quarters of the 75 cities coordinating afterschool programs in 2013 were still coordinating in 2020. [Two of the original 77 cities were left out of the study for methodological reasons.] In addition, 14 cities that were not coordinating in 2013 had adopted some coordination strategies.

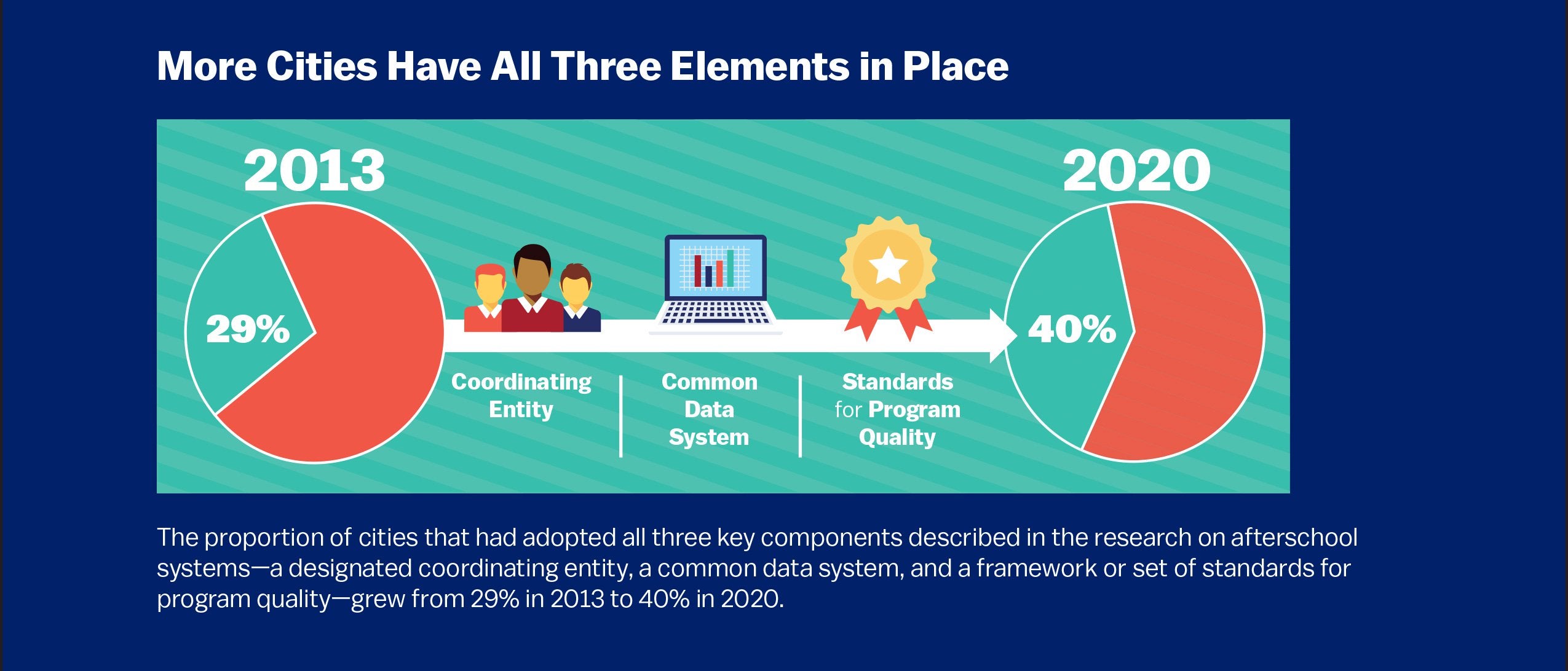

Our study of the cities that sustained coordination between 2013 and 2020 explored the extent to which they had the three key components [of an afterschool system]: a coordinating entity, a common data system and a set of quality standards or a quality framework. Overall, there was an increase in the proportion of cities with all three components (from 29 percent in 2013 to 40 percent in 2020). There was a decrease in the percentage of cities with a coordinating entity but increases in the percentage with a common data system or a set of quality standards, or both.

Not surprisingly, funding was an important factor in whether or not cities had these components. Seventy-one percent of the cities that sustained their systems experienced either stable funding or increased funding over the past five years. A much higher percentage of cities reporting funding increases had all three coordination components compared to cities where funding remained the same or decreased. Increased funding was highly correlated with the presence of quality standards or a quality framework, in particular.

The commitment of a city or county leader to afterschool coordination was also important, as it was in 2013. Eighty percent of the cities that were still coordinating in 2020 characterized their current leaders as moderately or highly committed to afterschool coordination. There was a significant association between a high or moderate level of commitment and having a common data system in 2020.

You found that at least three-quarters of the cities that were doing afterschool coordination in 2013 sustained their systems. What about the ones that didn’t? Were you able to identify possible reasons these cities dropped their systems?

A review of data collected for the 2013 study suggests that in some of these cities afterschool coordination was not firmly established (eight had one or none of the key coordination components). Another reason was turnover in city leadership, which brought with it changing priorities that resulted in decreases in funding for, and commitment of leadership to, afterschool coordination. In two cities, systematic afterschool coordination became part of broader collective impact initiatives.

You found that more afterschool systems had a common data system and a quality framework or set of quality standards in 2020 than in 2013, but fewer had a designated entity responsible for coordination. What do you make of these changes, particularly the latter?

Our finding that fewer cities had a designated coordinating entity in 2020 than in 2013 was surprising. Our survey question listed eight options covering different governance structures and organizational homes, so we’re fairly confident that the question wasn’t misinterpreted. We can only speculate about reasons for the change. It’s been suggested that mature systems may no longer see the need for a coordinating entity, which may be expensive to maintain. A coordinating entity such as a foundation or a United Way may have changed priorities, and systems may have collectively decided to operate without one, distributing leadership tasks among partners. Or cities may have been in the process of replacing the coordinating entity. This is one of those instances in which researchers generally call for further inquiry.

While it wasn’t within the scope of this study to investigate reasons for the increase in data systems and quality standards, we can speculate about why this occurred. More than half the cities that sustained their systems experienced increased funding, and that probably facilitated the development of both data systems and quality standards. One possibility is that, with the growing emphasis on accountability in the education and nonprofit sectors, funders may be calling for more supporting data. It’s also possible that cities or school systems decided to incorporate afterschool data into their own systems. It’s interesting to note that some respondents in cities without data systems were investigating them.

As for quality standards and assessment tools, we learned from anecdotal reports that cities had adopted templates and received training offered by outside vendors or state or regional afterschool networks, more so than came to our attention in 2013.

In the context of the pandemic and the racial justice movement, what do you hope that cities will take away from this report?

The findings of this study present a picture of progress in afterschool coordination before the full impact of the challenges caused by the pandemic and the reckoning with social injustice and inequality. We’ve since learned that systems have renewed their commitment to ensuring the growing numbers of children and youth living in marginalized communities have access to high quality afterschool and summer programming that meets their social-emotional needs. Statewide out-of-school-time organizations and others have rapidly gathered and disseminated resources and tools to aid the response of afterschool providers and coordinating entities. Some intermediary organizations have shifted to meeting immediate needs, while others have found opportunities to partner more deeply with education leaders and policymakers to help plan ways to reconfigure and rebuild afterschool services.

This study gives us reason to believe that cities with coordinated afterschool programs will be in a strong position to weather these times because of their shared vision, collective wisdom, standards of quality, and ability to collect and use data to assess need and plan for the future. Not surprisingly, funding and city leadership continue to be important facilitators for building robust systems, and respondents in both new and emerging systems expressed a desire for resources related to these and other topics.