This post is part of a series profiling the University of Connecticut’s efforts to strengthen its principal training program. The university is one of seven institutions participating in Wallace’s University Principal Preparation Initiative (UPPI), which seeks to help improve training of future principals so they are better prepared to ensure quality instruction and schools. A research effort documenting the universities’ efforts is underway. While we await its results, this series describes one university’s work so far.

These posts were planned and researched before the novel coronavirus pandemic spread in the United States. The work they describe predates the pandemic, and may change as a result of it. The University of Connecticut is working to determine the effects of the pandemic on its work and how it will respond to them.

Richard Gonzales, director of the Neag School of Public Education’s University of Connecticut Administrator Preparation Program (UCAPP), wrote on this blog about the significant changes the program had to take on as part of Wallace’s University Principal Preparation Initiative. Few feel these changes as acutely as the program’s faculty members, who must revamp long-established approaches to fit the program’s new curriculum.

Six of these faculty members met earlier this year at the UConn Hartford campus in the historic Hartford Times Building to discuss changes in the program thus far, elements that appear to work well, elements that present some challenges and directions the program may take in days and years ahead. Wallace’s editorial staff had the opportunity to listen in and report back.

No course is an island

UCAPP, like many principal preparation programs, was once a collection of courses with few explicit connections among them. Students would study one course every semester, each focused on different regulatory requirements, with little discussion of how topics covered in different courses could interact. The curriculum is now more interconnected, said Erin Murray, assistant superintendent for teaching and learning in Simsbury Public Schools who teaches courses on instructional leadership at UConn. Students revisit key concepts of leadership throughout the program to ensure they can apply them in a variety of different situations.

“From what was a more isolated, topical approach to instruction,” Murray said, “we've gone to a more integrated crossover opportunity that topics will re-emerge throughout the two-year program.”

Students now complete two courses every semester, all of which have moved from a focus on narrow topics to one on broad competencies of leadership. A course that was once limited to supervision and teacher evaluation, for example, is now part of a broader set of courses that teach talent management, including recruitment, retention and team leadership. Three strands of leadership—instructional leadership, organizational leadership and talent management—are now woven together, with courses interspersed throughout the two years of the program.

The change requires faculty to work out how their courses fit into a larger program, said Howard Thiery, superintendent of the Harwinton-Burlington regional school district who teaches courses on organizational leadership. “Each of us is trying to deliver on this high-quality experience within our course and figure out how it integrates,” he says. “Are we delivering on the integration? I don’t know yet. It’s early.”

As an example, Thiery pointed to two courses: one on organizational leadership, which he teaches, and another on instructional leadership. Similar courses would once have been taught in different semesters, but his course now immediately follows the other in the same semester. “The two courses in a semester come literally back to back,” he said. “[Students] end one course on a Monday and the following Monday they’re in a new course.”

His course work must now gel with the one that now precedes it. “I couldn’t ignore the fact that they had just come from [that] course,” he said. “I had to show them that although these are different strengths in our program, instructional leadership and organizational leadership in the actual practitioner are integrated daily. One impacts the other; they are part of a system.”

When his students present their work on learning targets and assignments, for example, he tries to connect it to school culture. “If these are your learning targets for kids,” he asks his students, “what does that say about your school values? How did you engage parents?”

The juxtaposition of courses forces him to keep the bigger picture in mind, he said. “I was just reacting to where my students were,” he added. “It wasn't so much by design as by demand.”

More work for instructors…

The new setup places many other demands on faculty. Chief among them, instructors say, at least while they iron out the kinks, is communication. Richard Gonzales, director of UCAPP who also teaches courses on organizational leadership, said that instructors must share much more information with each other to stay in sync. “We had talked plenty,” he said, speaking of previous iterations of the program, “but we'd never exchanged our plan for the sessions. That's a noticeable shift”

Yet more may be necessary, said Kelly Lyman, superintendent of schools for Mansfield Public Schools who teaches instructional leadership. “It seems like there’s going to need to be more opportunity for us as instructors to understand the whole two-year program and what’s taught where so that we can help make those connections,” she said.

Thiery agreed. “What did you do right before me and what did you do right before her,” he said. “Finding the mechanisms for that are going to be key.”

The new curriculum also requires instructors to reduce their reliance on rubrics and checklists to develop course syllabi. “Looking at the competencies,” said Lyman, “forces me to think beyond just the content of course.”

Broader course guidelines could help instructors make this shift, said Charles “Chip” Dumais, who teaches courses on instructional leadership and serves as executive director of Cooperative Educational Services, a nonprofit that supports area schools. “A rubric that is based on the competencies—that includes an element of connections to the other work they've done—supports what we're asking them to do in the program,” he said.

Instructors must also become much better versed with their own material, Gonzales suggested. They must now examine their classes from many diverse perspectives and cannot fall back on standard practices that had changed little in many years. “We were students of our own content more this time around,” he said. “We re-read certain things, we assigned new things for the first time … and we were much more attuned to the preparation.”

That extra preparation is also necessary to meet the pace of the new curriculum, which puts students through two courses per semester instead of one. “We’re a little bit more focused on staying on schedule now,” Gonzales said.

Still, said Dumais, the quicker pace and extra effort could help instructors bring more value for their students. “If all of talent management is condensed into one semester,” he said, “it really doesn't allow you to do all the things that you'd need to do.”

… could lead to benefits for students

Instructors hope that their extra work will help give students a more complete picture of the principalship. “I experienced the balance,” said Eric Bernstein, assistant professor in educational leadership. “Students are doing more than one thing at the same time.”

That cross-pollination of ideas, Murray suggested, is especially important given the breadth of experience of UCAPP students. “The backgrounds that the people come to in the program are so vastly different,” she said. “You could have a school psychologist, a guidance counselor, school counselor, first-grade teacher, a special-ed teacher. To integrate it in this redesign is extremely powerful to get them to better understand the full picture of what leadership is going to look like for them.”

It also keeps students engaged, said Thiery. In previous versions of the curriculum, students who had greater experience with school culture may have had to take a back seat for a year while courses focused on curriculum. That is no longer so. “We immediately hopped [from a course on curriculum] into a school culture and climate course,” he said. “And the school psychologist and school counselor all of a sudden had legs way up on many of the other students in the class. They got see their own value and their own strengths.”

The redesign could also make students’ internships more meaningful. Lyman suggested that the previous program design could often limit the work students did as interns. “It used to be, well, don't do anything on curriculum until you get to semester four, because that's when we teach it,” she said.

“Now,” she added, “I'm hoping that there's a little more opportunity in a more natural way for them to make those connections.”

Ultimately, said Thiery, the new structure shifts from academic requirements and forces instructors to help build students’ professional skills. “One of the biggest shifts we have to do is get them into a professional mindset,” he said, “which gets out of the ‘how many pages, what font, how many references’ mode of instruction.” The new design requires him to focus on larger competencies. “Here's your standard, here's your professional competency, here's what it would look like in practice,” he said. “It is about being a practitioner.”

It’s not easy being green

New approaches bring many potential benefits, instructors suggest. But the program has much to learn and glitches to fix before it can claim success. Administrators are constantly collecting feedback from students, instructors, school districts and other partners to ensure it is on the right path.

“The first time we're doing it it’s going to be clunky,” Bernstein said, suggesting UCAPP must be open to criticism as it tests its new waters. But, he said, it must also be judicious about the feedback it chooses to act upon. “How do you differentiate between being responsive to the students’ concerns and letting something work before you stop trying it?” he asked.

“How do we take our reflections and feedback and figure out what is structurally deficient,” added Thiery, “and what is actually developmental on the student's end?”

One concern is the amount of time the program demands from its students. “The classes meet weekly for students who are full time educators,” said Lyman. “They've already had some leadership experiences in their school or district and now we're asking them every week to meet with us. I just wonder about the absorption rate and the application.”

Some wondered whether this pace is causing students to brush over essential elements of the program, especially the core assessment, a measure of the extent to which students meet established standards of school leadership. Students are expected to check progress against the core assessments throughout their time in the program, but some instructors worry that these assessments get buried under other demands.

“The pace is rapid and I think that that might be more of an issue for us in the design than for them in the work,” said Dumais. UCAPP may have to work harder, he suggests, to demonstrate the importance of each of its components, including the core assessment. “In order for the core assignment to be parallel [to curriculums and internships,]” he said, “we have to make the conditions for the core assignment to be parallel.”

Faculty members are soliciting and receiving feedback from students and partners to respond to such concerns. “It seems that there's something about the way this [iteration of the program] is working, or the way that we're approaching it, that we're listening more,” said Gonzales.

“If you listen to what you've said today,” he said to his colleagues, “there's a greater awareness of what you know and don't know. We understand what is happening or not happening, or what needs to be done, more than we did eight years ago.”

Do try this at home

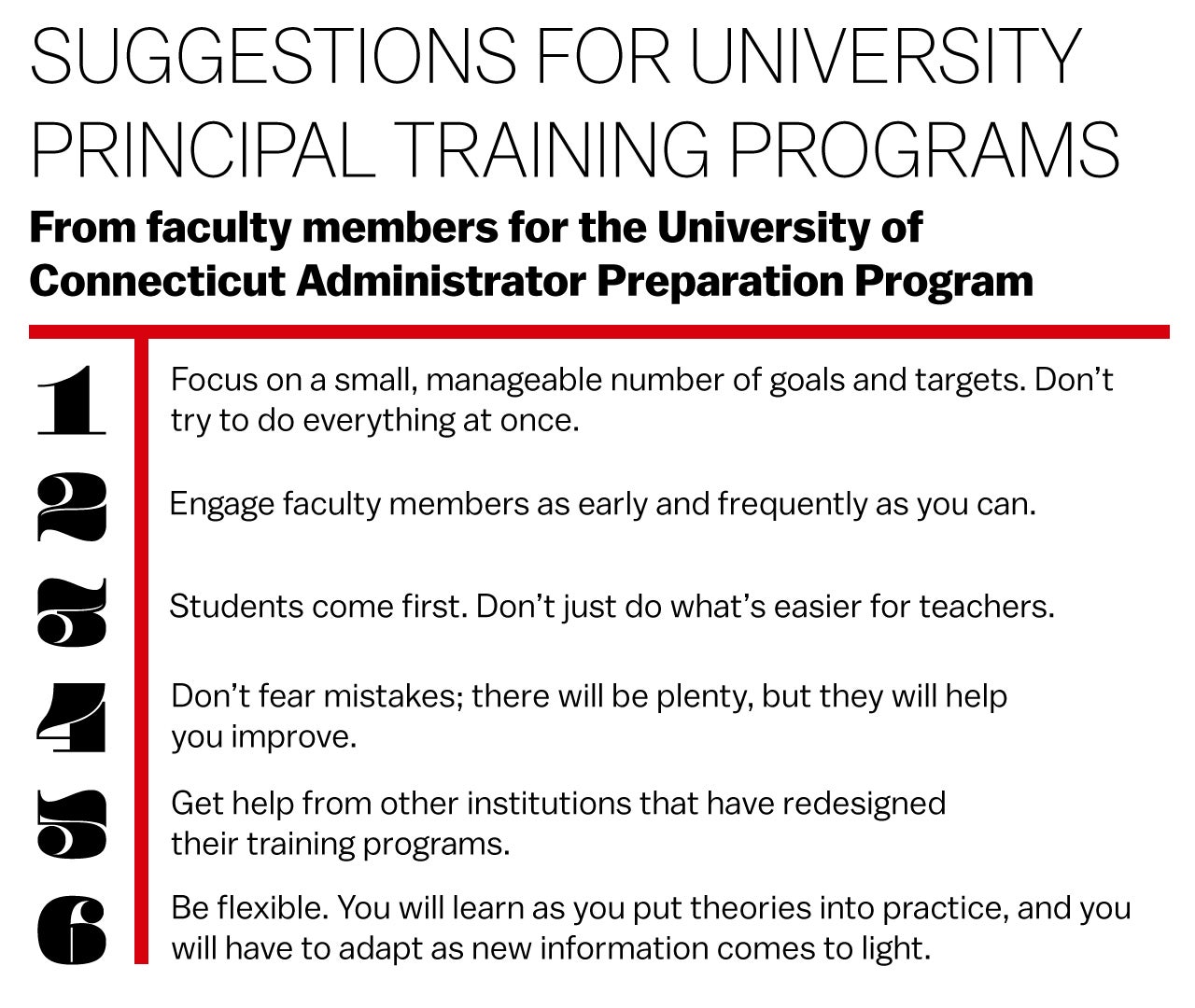

While the results of the work are still unclear, each of the instructors had advice for others who may embark on similar initiatives.

Faculty members can be key, said Lyman. “Engage faculty members as frequently as you can from the start to really build the understanding,” she said. “This program would not be successful if people in it, teaching it, working within it, don't understand the big picture of their program.”

An experienced partner could help, said Murray. The University of Illinois at Chicago had previously redesigned its own principal training program and helped guide UCAPP, a support Murray thought was critical. “The collaboration we’ve had with University of Illinois was exceptional,” she said. “Having outside people talking with us about other work that they've done and looking at other programs I think was extremely powerful.”

Don’t be scared of mistakes, said Thiery. “Even in the best of planning and design circumstances, where you have all the time in the world, when you finally push the go switch, there's still going to be this feeling that you're making it up,” he said. “The checking in with students more often comes from our own acknowledgement that we're building the plane and flying it at the same time. … I think to some degree that intensity is making us better. You have to be willing to do it and not be afraid of it.”

Stay focused, adds Bernstein. Equity and the student’s identity as a leader were the two guiding principles for the program, clear targets he found helpful. “These two things should be thought about in all of the ways that we're designing every piece,” he said. “Not these 12 or 18 or 36 things. Not these broad general notions, but these two very specific things.”

Students come first, said Dumias. “I don't think that the first thing that comes to mind when people ask about great teaching is college or graduate school. Things that are good for students, they become slightly inconvenient for teachers,” he said. “I think that this program is a perfect example of how this teaching staff are changing their perspective on how to change the structure so it best meets the needs of students.”

And design is just the beginning, said Gonzales. “Don't underestimate or discount implementation as part of the redesign,” he said, adding: “It's the first cycle of implementation and the adjustments based on lessons learned … that's part of redesign. Make sure that you plan for that.”

STORIES FROM UCONN PRINCIPAL PREP PROGRAM