Wallace recently released a research report that contained a welcome—and unusual—finding for those interested in improving public K-12 schools: A change initiative had succeeded in moving the needle on student achievement. The report, Principal Pipelines: A Feasible, Affordable, and Effective Way for Districts to Improve Schools, detailed RAND Corporation research into what happened when six large school districts introduced a systematic approach to developing school principals.

But a bit overlooked in the initial burst of news and social media accounts of the achievement findings was another important nugget from the report. The approach to developing principals, known as building a principal pipeline, was a boon to school leader retention, too.

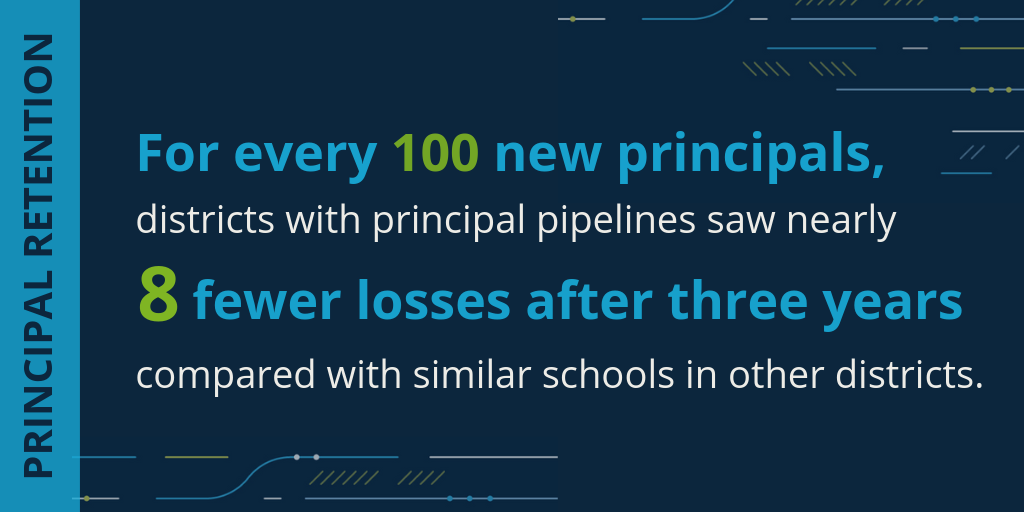

Specifically, newly placed principals in the six districts were almost 8 percentage points more likely to remain in their schools for at least three years than newly placed principals in comparison schools in other districts. That means that for every 100 newly placed principals, pipeline districts experienced eight fewer losses than the comparison districts.

This matters because principal churn is a problem for many districts. The annual turnover rate of principals in U.S. public schools was about 18 percent in the 2015-2016 school year, according to U.S. Department of Education figures cited in the report, and higher still for schools with large numbers of disadvantaged students. There’s a price to be paid for this. Replacing a principal costs about $75,000, the report says, pointing to research on the topic. The cost in disruption to schools, teachers and students is high as well. Why? In part because rapid turnover undermines a simple necessity—the actions that principals take to try to improve student performance need time to be carried out and bear fruit, according to other research the report points to.

.jpg) The effects of the pipeline on retention could not be measured with as much precision as student achievement, but when the six pipeline districts are pooled together in one analysis, “we find a robust, statistically significant result,” says Susan Gates, lead author of the RAND report. Variation in retention across these districts could possibly be attributed to such factors as how many principal vacancies each district faced year-to-year in the five-year initiative, which began in fall 2011, and the different ways the districts approached principal reassignment. For example, some districts may have been inclined to move a new principal who had performed well in two years to another school with greater needs.

The effects of the pipeline on retention could not be measured with as much precision as student achievement, but when the six pipeline districts are pooled together in one analysis, “we find a robust, statistically significant result,” says Susan Gates, lead author of the RAND report. Variation in retention across these districts could possibly be attributed to such factors as how many principal vacancies each district faced year-to-year in the five-year initiative, which began in fall 2011, and the different ways the districts approached principal reassignment. For example, some districts may have been inclined to move a new principal who had performed well in two years to another school with greater needs.

Additionally, the pipeline’s positive effect on retention seems to have generally increased over time. Principals newly placed in pipeline-district schools in the initiative’s fourth year, the 2014-2015 school year, had a three-year retention that was close to 17 percentage points higher than the retention of newly placed principals in the comparison schools in other districts. “That’s encouraging evidence and what I would have expected to see,” Gates says.

The reason, she explains, is that the pipeline approach to developing effective principals consists of implementing a set of policies and practices—such as high-quality pre-service training, data-informed hiring and appropriate on-the-job support—and some these likely needed more time than others to unfold and have an impact on cohorts of newly placed principals. Changes in hiring procedures or job support, for example, could have yielded results almost immediately. Improving pre-service training, on the other hand, would likely have had a delayed effect because candidates who completed revamped programs would not typically have been hired as principals for several years. “I would expect that with retention, in particular, that over time, those outcomes would improve—as districts build a more robust hiring pool through revised pre-service, candidates are selected based on a more rigorous approach and principals are supported more effectively,” Gates says.

The RAND report was part of a wide-ranging study of the Principal Pipeline Initiative conducted with Policy Studies Associates, which in a series of reports examined the initiative’s implementation in the participating districts—Charlotte-Mecklenburg, N.C.; Denver; Gwinnett County, Ga. (outside Atlanta); Hillsborough County (Tampa), Fla.; New York City; and Prince George’s County, Md. (outside Washington, D.C.).

A follow-up study by Policy Studies Associates, published in February this year, provides additional evidence of the benefits of pipelines for retention. In Sustaining a Principal Pipeline, which looks at the pipelines’ status two years after Wallace support for the initiative ended, officials from three districts reported they were keeping tabs on turnover to gauge the results of the pipeline work and determine how many principal vacancies would likely need to be filled.

All three—Charlotte, Denver and New York—said they had seen improved principal retention, according to the report. That’s a good result as far as the districts’ leaders are concerned, according to Brenda Turnbull, who co-led the Policy Studies Associates research.

All three—Charlotte, Denver and New York—said they had seen improved principal retention, according to the report. That’s a good result as far as the districts’ leaders are concerned, according to Brenda Turnbull, who co-led the Policy Studies Associates research.

“What districts want, not surprisingly, is to put good principals into schools that are a good fit, have them stay in place for years, and then maybe transfer them to another school that needs them or promote them to a principal supervisor position,” she says. “From the perspective of a responsible district leader, a struggling principal who quits or isn’t renewed is a sign that something has gone wrong with preparation, selection and placement, or ongoing support. So when retention was increasing, these pipeline districts saw that as validation of their pipeline efforts. It was something that they had been working toward. Of course some turnover is inevitable and can be healthy, but no district really wants to have revolving doors in its principals’ offices.”

One note for those interested in pursuing pipelines as a retention strategy: A recent analysis finds that RAND’s retention research is strong enough to meet federal evidence-of-effectiveness criteria for funding under the Every Student Succeeds Act, including its Title I stream.

To see more about the Principal Pipeline Initiative, check out this page.