Basing decisions on reliable, pertinent information is a smart idea for any human endeavor. Talent management is no exception. That’s the reason a number of Wallace-supported school districts in recent years have undertaken the difficult task of building “leader tracking systems” in the service of developing a large corps of effective principals.

![]()

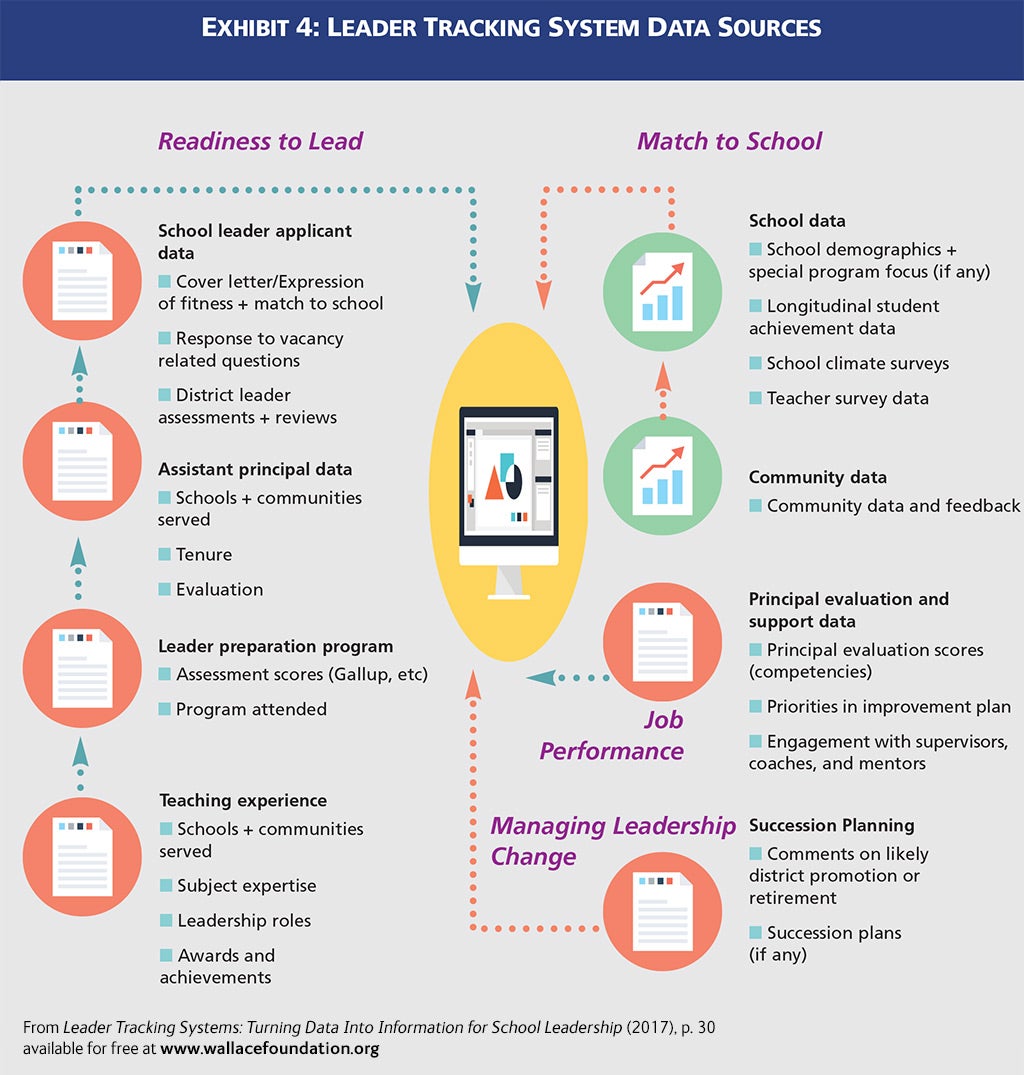

A leader tracking system is a user-friendly database of important, career-related information about current and potential school leaders—principal candidates’ education, work experience and measured competencies, for starters. Often this information is scattered about different district offices and available only in incompatible formats. When compiled in one place and made easy to digest, by contrast, the data can be a powerful aid to decision-making about a range of matters necessary to shaping a strong principal cadre, including identifying teachers or other professionals with leadership potential; seeing that they get the right training; hiring them and placing them in the appropriate school; and supporting them on the job.

In a panel discussion during a Wallace gathering in New York City this week, representatives of two districts that have built leader tracking systems talked about their experiences. Their assessment? The effort was worth it, despite the reality that constructing the systems required considerable time and labor.

Jeff Eakins, superintendent of the Hillsborough County (Tampa, Fla.) Public Schools, said the data system has proved invaluable to “the single most important decision I make…the hiring of principals.” That’s because the system can give him an accurate review of the qualifications of job finalists along with a full picture of a school that has an opening, he said. Similarly, in Prince Georges County, Md., (outside of Washington, D.C.), Kevin Maxwell, the chief executive officer of the public schools, said he is now able to compare a “baseball card” of candidate data with school information, thus getting the background he needs to conduct meaningful job interviews—something he does for all principal openings. With the information from the data system, he says, “I have a feel for what that match looks like.”

For their part, two people who were instrumental in the development of their districts’ leader tracking systems—Tricia McManus, assistant superintendent in Hillsborough, and Douglas Anthony, associate superintendent in Prince George’s County—offered tips for others considering whether to take the plunge. From McManus: Expect construction to take time. Hillsborough’s system took “several years” to be fully functional, she said. From Anthony: Find a “translator,” someone who can bridge the world of IT and the world of the classroom, so educators and technology developers fully understand one another. From both: Once the system is completed, know that the job isn’t done. Information needs to be regularly updated and kept accurate.

Want to find out more? A report from researchers at Policy Studies Associates examines the uses of leader tracking systems in six Wallace-supported school districts and provides guidance based on the districts’ system-building experiences. This Wallace account shows how leader tracking systems helped districts end such difficulties as job-candidate searches through “a gajillion résumés.” Also, listen to Tricia McManus and Douglas Anthony discuss their districts’ work to build a strong pipeline of principals in Wallace’s podcast series, Practitioners Share Lessons From the Field.