“What would I wear?” That age-old question is not simply the whining of a teenager facing a monumental quandary despite a closetful of clothes. It’s one of the many questions that newcomers ask when deciding whether or not to partake of the arts.

Among the others: Will I know what to do? Will I see members of my peer group there? Will I feel included? Will I like it? Is it for me?

Over the last few decades, in the deep belief that the arts belong to everyone, The Wallace Foundation has funded audience-building initiatives at many arts organizations; it’s now in the middle of a six-year, $61.5 million “Building Audiences for Sustainability” program. Reviewing theoretical and data-driven research, along with practical experiences from arts organizations over the past 10 years, Wallace and its partners have developed a much better understanding of the reasons people choose to go, or not to go, to an arts performance or exhibition.

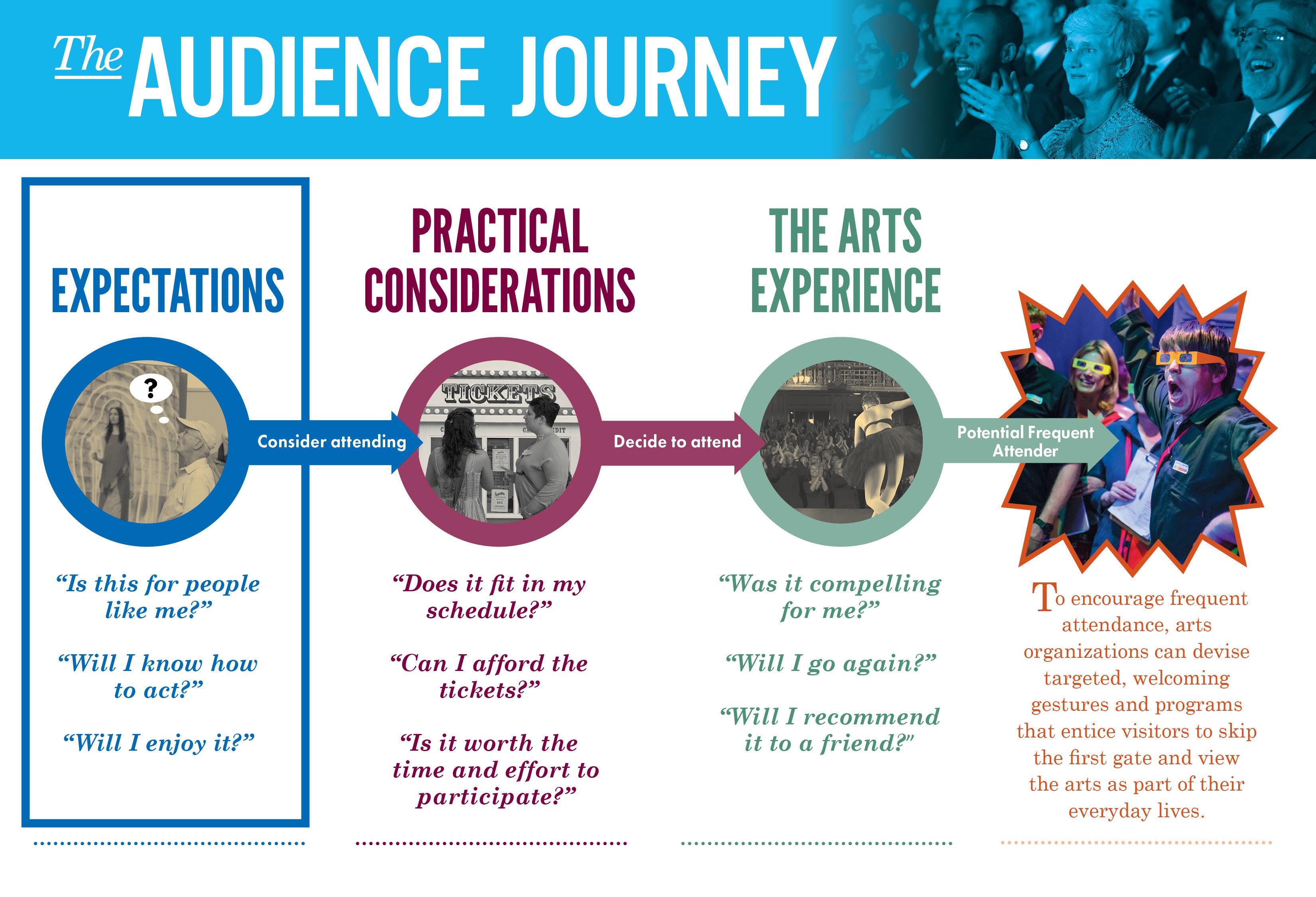

The decision is not a simple case of yes or no. It’s a series of decisions that could be construed as a journey with gates set up along the way. At each one, some people will choose to continue on, while others will drop out. At the first juncture, people tend to consider, usually subconsciously, many questions about their expectations of an arts opportunity—with answers that can be influenced by arts organizations intent on building their audiences.

Sometimes all it takes is a small gesture or more information; sometimes, more.

For example, because young people had told the Opera Theatre of St. Louis in focus groups that they didn’t know what to wear to an opera, OTSL posted pictures of audience members in all manner of dress, casual and fancy, on its Facebook and Instagram pages. That was one question taken care of, with a reassuring answer—wear what you want.

When Ballet Austin discovered that potential audience members were turned off by its promotional materials for contemporary works—and didn’t know what to expect, let alone if they would like it—the company changed tactics. It discontinued traditional open rehearsals, popular with regular attendees but not new people, and instead started Ballet Austin Live! That’s a 30-minute livestream of a rehearsal that allowed more, and different, people to see what a production might be like before they bought tickets.

To make sure that millennial visitors to the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum felt comfortable at its “Third Thursdays” evenings—which feature gallery games, music, hands-on artmaking, food, and drinks—the museum recruited volunteers from the same generation. They provide a welcoming, unintimidating presence, answer questions about the art on view, and sometimes even join in the games by offering helpful hints.

Pacific Northwest Ballet, which once was viewed by teens as boring and stuffy, conquered the “it’s not for me” syndrome with a raft of measures including teen-only previews of PNB’s annual choreographers showcase, increased Facebook activity about the company’s performances, and behind-the-scenes videos.

Changing attitudes—which is what these measures aim to do—isn’t always easy, especially if they were formed by a negative previous arts experience or are ingrained within a person’s social group. But with specific overtures to hesitant individuals or reluctant groups, some arts organizations are countering misperceptions that may prevent some people from attending an arts experience and attracting new audiences.

This three-post series outlines the Audience Journey, a conceptualization of people's decision-making process when choosing to attend an arts performance, exhibition or event. This post suggests ways organizations might engage people who are less inclined to attend or visit. The next two posts cover how to combat the practical barriers of attending and how to create a rewarding experience that makes people want to return. All posts originally appeared on the National Arts Marketing Project's blog and are reprinted here with permission.