Recent studies have shown that creating art can help young people make sense of the world around them, process their feelings and deepen empathy. After the pandemic hit and programs scrambled to go online, making art also became a source of healing, connection and, ultimately, resilience, as well as increasing broader access to arts programs for more youth across the country.

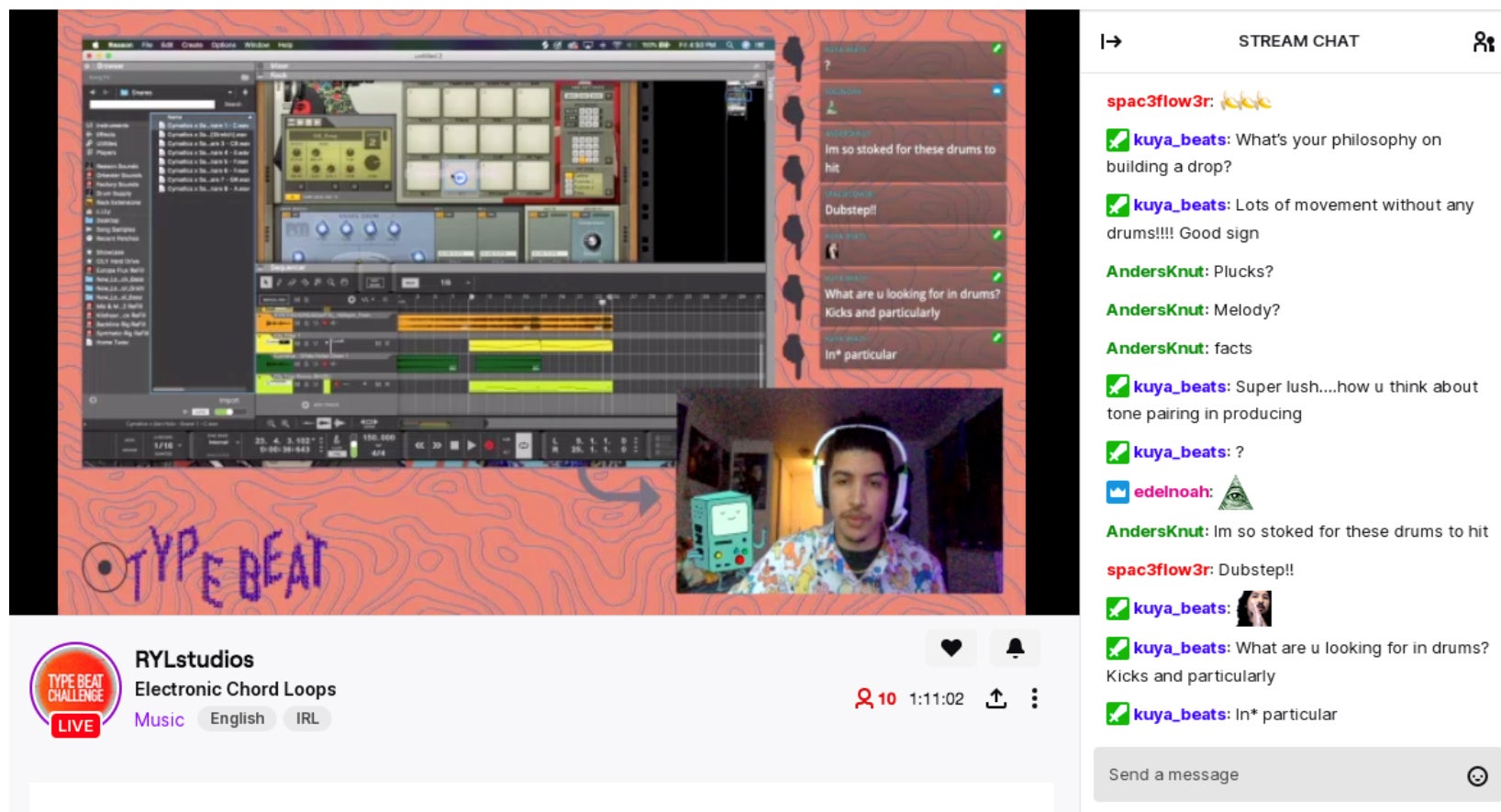

The Wallace blog caught up with researchers involved with two arts learning programs to get a sense of the specific lessons they learned in the pivot to virtual learning and what we all might carry forward. Tracey Hartmann, Ph.D., is the director of qualitative research at Research for Action in Philadelphia and has been working with Wallace for a decade on our Youth Arts Initiative with the Boys & Girls Club of America (BGCA). All five BGCA clubs from different parts of the country stayed open during the pandemic, offering some form of virtual, in-person and hybrid programming. Monica Clark, Ph.D, is the Teach YR project director at YR Media–a national media, technology and music training center and platform for emerging BIPOC content creators headquartered in Oakland, California. She leads the organization’s research team and conducted this research project collaboratively with colleagues Lissa Soep, Ph.D., and Nimah Gobir, ME.d. The pandemic gave birth to YR’s Type Beat Challenge, managed by Oliver "Kuya" Rodriguez and Maya Drexler, which allowed young people to create and submit music from anywhere, collaborating with one another and with professional music producers around different themes.

Hartmann and Clark were meeting each other personally (on Zoom!) for the first time and had a lot to say about young people and the arts. The conversation has been edited for space and clarity.

Wallace Foundation: In your work with the BGCA clubs, Tracey, you found that in moving to virtual there needed to be a higher level of what you called “intentionality” in programming. Can you give an example of what you mean? And then, Monica, does this resonate with your findings too?

Tracey Hartmann: Our data comes from focus groups we did with 31 youth participants across the five clubs, and what we heard from youth was that what engaged them in the virtual programming was very similar to what engaged them in person. But from the teaching artists’ perspectives, they found that they had to be more intentional about the things they did, and there were three elements that came up. The first was for young people to have input into programming. The program was designed for middle school youth–and sometimes older–an age group that is really hard in any setting. So the artists had to make an effort to learn what the young people were interested in, sometimes on an individual level, and be more intentional about following these interests, even outside of the Zoom class.

Artists also had to be more intentional about connecting with youth, checking in at the beginning of class. For example, one artist said he had to make an extra effort to know who was shy and didn’t want to be on camera or what was going on for them that day. We also heard from youth that they wanted more verbal guidance, especially if they were learning new skills, to help them feel like they were getting the kind of hands-on support they might get in person.

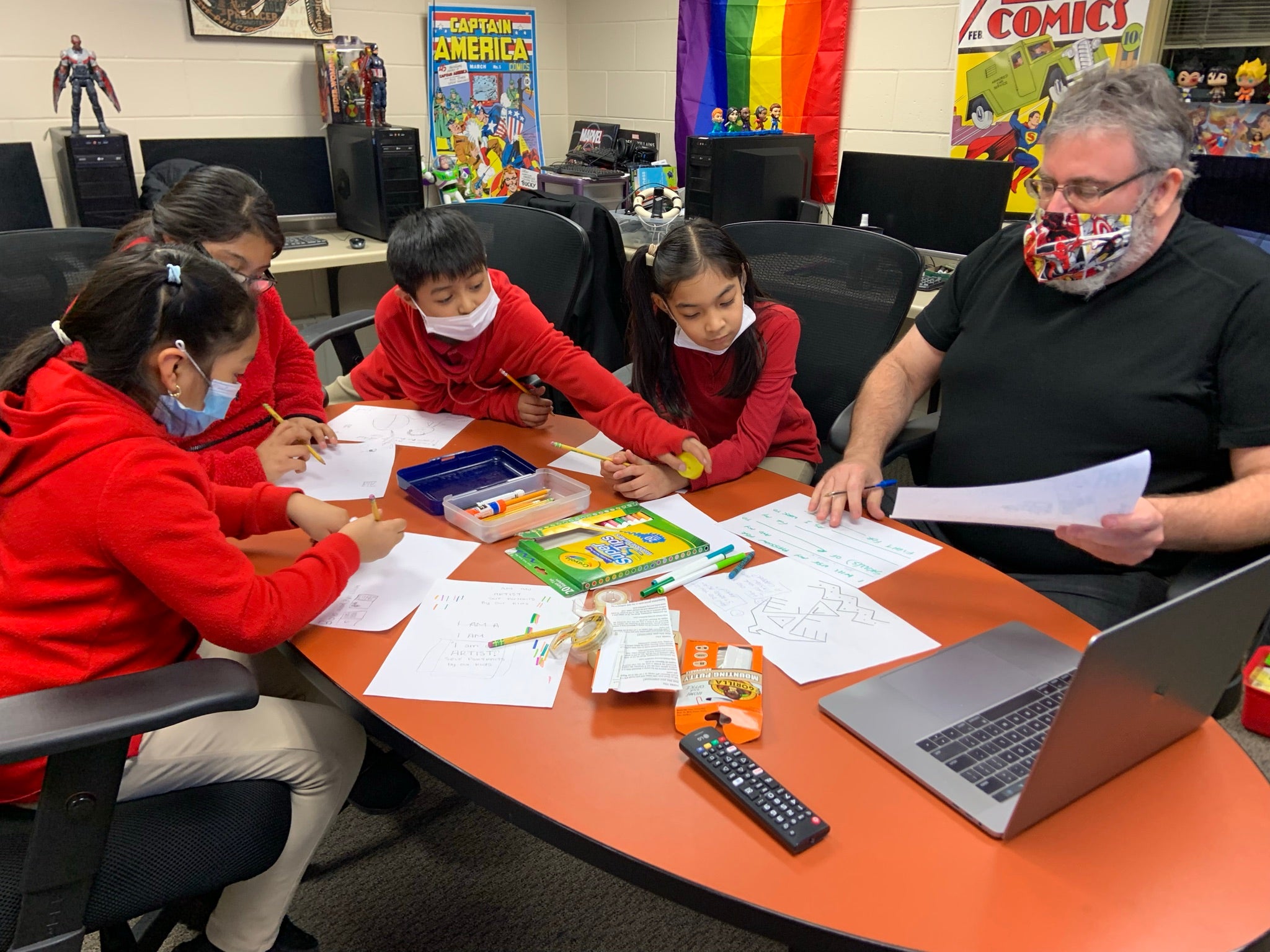

Finally, the artists had to be intentional in thinking through how to do the hands-on art, making sure young people had the supplies or equipment they needed. Sometimes they delivered art supplies or sent home packets to young people. They also found that youth really appreciated watching them do the art.

Monica Clark: So much of what Tracey just shared mirrors findings from our focus groups with about 40 people. We also held a convening where we brought together leaders from five different arts organizations to talk about the pivot to virtual. One of our instructors from that convening said something to the effect of “I’m shouting out into the void,” talking about the black screens, and the vulnerability involved in trying to engage students virtually and get them to turn their cameras on. How do you build community around that?

One of the things that made our Type Beat project so successful for virtual was that it was co-designed with and by youth. We took advantage of remote platforms by opening up the program to young people outside of the Bay Area or to those who might not have been able to access the program in person. Doing this also highlighted the glaring inequalities that young people could face going online: access to computer hardware and software, because with music production it’s not just your laptop but the software that’s going to help you bring the beats together; unreliable broadband and wifi access; equal resources and training for teachers; and a lack of basic social and economic support for our most marginalized students in their communities.

We knew we needed to meet people virtually where they were already hanging out online, and we did this by using eight different platforms. We also collaboratively created community norms for how we were going to operate as a community in the virtual space. These were specifically outlined and always pinned up in the chat. We were always thinking about how to create a positive community space focused on mental well-being. One of the Type Beat challenges was something like “chill beats for wellness,” so the young people could build that into the art they were making.

WF: How did the teaching artists specifically need to change their practice in the virtual world? And what kind of support or tools did they need to be able to teach their art in this way?

MC: In some ways they were doing the things that were already done but learning how to do them in the virtual space. Of course, we always want to support our young people when they're showcasing their art. We want them to feel confident in what they're producing. But how do you do that when they're in their bedroom and you're in your apartment or wherever you are? For the Type Beat challenge, we asked our instructors to support young people in developing the design aesthetic of the background space of their room, knowing that we were asking them to be very vulnerable in showing their space.

Then there are the kinds of interpersonal and community building activities that are needed in any space, but you need to be even more innovative in the ways that you do it in the virtual space. For instance, you could support students on screen by doing a hype up dance that each person would perform in their own space, so the whole group would be together dancing and getting each other excited. It helps break the discomfort and model that it’s safe to be vulnerable in this space.

TH: Monica was referencing physical and emotional well being before, which is one of the 10 principles [for developing high-quality afterschool arts], and which was definitely coming up around people feeling shy about having their camera on. The artists worked to help young people create virtual backgrounds. They were aware that family members were also in the room, and some artists used that as an opportunity to invite them into the conversation or the activity. In fact some of the young people in focus groups suggested that it would have been okay for the artists to ask them to turn on the camera more often to show their work.

The instructors also needed basic tools. In addition to having the wifi capacity, maybe good cameras, microphones, lighting. There was a certain software that dance artists needed that helped them sync music with their video. Some of the TAs were digital artists, so they already had a lot of tech skills, and they ended up being kind of advisors to other staff in the club. But others did not have those skills, and it was a steeper learning curve for them. They needed more training and professional development to develop the skills to be able to offer programming virtually.

WF: What did you learn about how young people used art during the pandemic to support their mental health, process their feelings, support civic engagement or anything else?

MC: We found that young people turned to art as an escape from what is happening in the world and also in trying to make sense of and reshape what they're experiencing under these extreme and uncertain conditions. They are using art as a social intervention to formulate and share their points of view, connect with others and mobilize for equity and justice. One of our young people said, “I think my view on art has definitely changed, and now I see it, less of something, just like doodling or whatever, and more as a tool that I can use in my life moving forward.” Another one of our national correspondents from Minneapolis was talking about a journalism piece she published with YR during the George Floyd protests, after his killing, and how it was one of the most difficult things that she ever wrote, but it was also the most powerful and it made her feel so good afterwards–particularly due to the fact that she was able to work with a Black editor that she looked up to in making final edits to her piece.

The prevailing assumption was that the pandemic lockdown meant that young people could not go anywhere, that everyone was stuck in their house and trapped. But from a number of our focus group participants we found that the same conditions also enabled young people to explore more widely than before, forming new communities through digital access to faraway places and professional artists.

TH: We saw that youth created artwork about Covid, about racial injustice, about grief and loss. It was a coping mechanism and a way to calm their nerves. Some young people needed opportunities to process some of the things that were going on in the world. But the program also served youth as young as nine, and maybe even younger, and for them it just took their mind off of what was going on, helped them feel “normal” or represent their private experiences. An instructor at one club described a song that his class created called quarantine crazy where youth were rapping and singing about their experiences during Covid.

The teaching artists were always responsive to where young people were at any given day and created the space, if needed, for them to talk about what was on their minds. Again this was particularly so for the older youth, who often wanted that space to talk about things. One artist said, “I feel as if I'm a counselor and an art teacher when they're sharing with me, and if I affirm how they feel, hopefully that makes some type of positive impact.”

WF: What unique role do you see art making continuing to offer young people, and how can we best support both the practitioners and the organizations that are dealing with them as they do this?

MC: We are focusing now on the idea that STEAM [science, technology, engineering, arts, mathematics] implementation can be built on solid foundations and serve genuine opportunities for deep learning at the intersection of creative and technical disciplines. Our young people are creating art but they're also learning the technical side of packaging, developing and creating music, which is a tech skill.

It’s also important to remember that we are freed from many of the constraints of schools, including short class periods, mandated use of grades, academic tracking limits on admissible subject matter. Out-of-school-time afterschool arts educators, who are often working artists themselves, can help support young people in the creation of creatively and socially challenging products that are guided by the young people and the issues that they want to be addressing.

TH: The artists described how they themselves needed support in these roles. They needed to know who to go to for referrals if issues came up that were beyond their ability to respond to. They needed more training in areas related to social and emotional well-being. For example, they received training in how to manage their own emotions to support young people. They received some training around supporting youth experiencing trauma, but they would have liked even more of that training. They received training around setting appropriate boundaries, because in the virtual space, the boundaries are a little different. How to de-escalate intense situations–this was for artists that were back in person–and then again just responding to grief and loss, because that was coming up a lot.

WF: Any final words of advice for other organizations who are thinking about expanding their virtual arts learning or other models that include some people being online while others are in person?

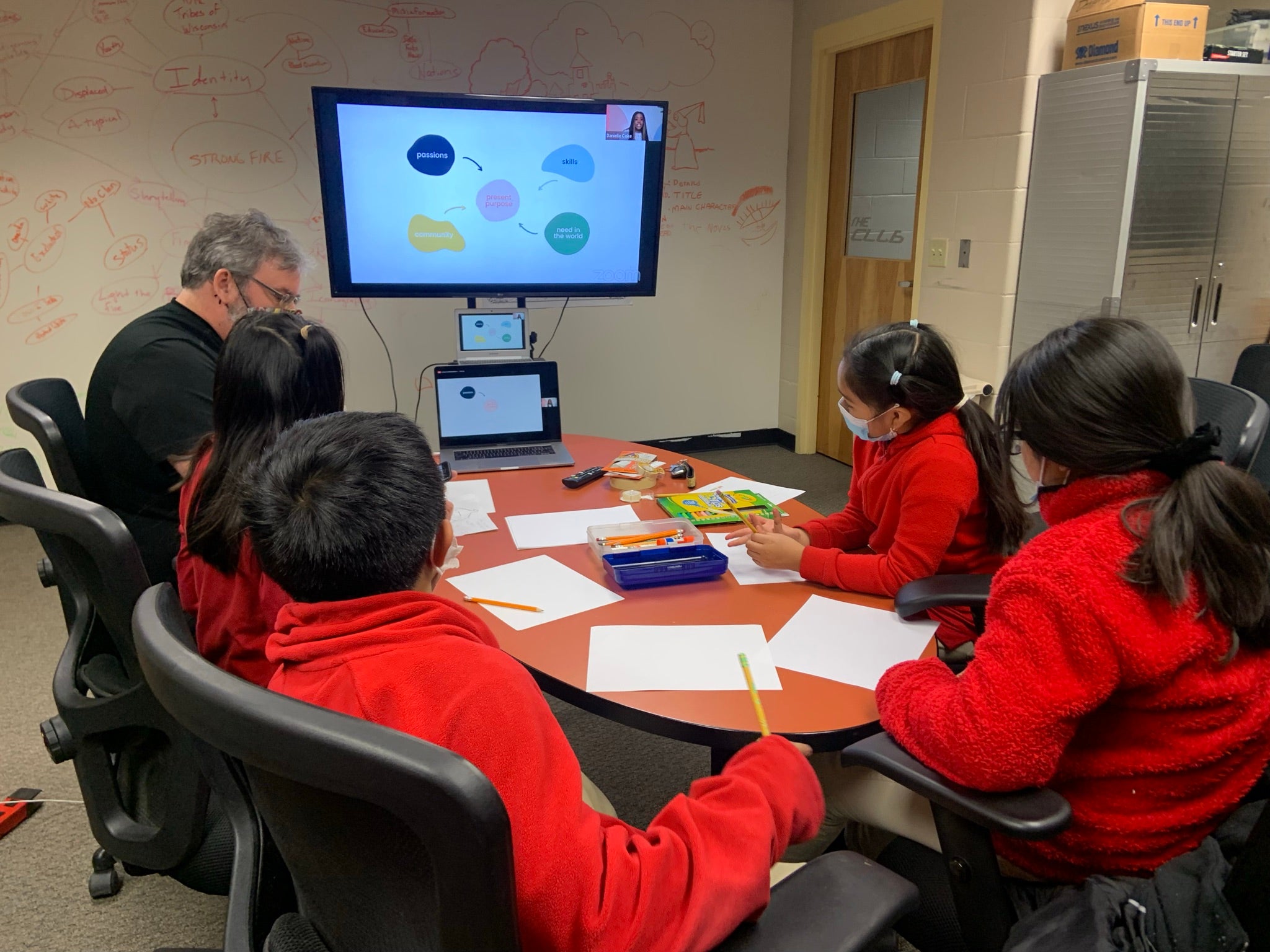

TH: One of our takeaways was that the synchronous model, which is live programming on Zoom or a similar platform, works best for youth who are really passionate about the art form. We heard from the artists as well that you have to be really motivated to do virtual synchronous programming. The hybrid model that the clubs used with the artist Zooming into the in-person classroom seemed to work well, especially if the artist was able to be in the club occasionally. It works better for exposure programming, meaning programming that allows youth to try out an unfamiliar art form to see if they like it. The hybrid model also has promise for bringing in artists from all over the country, which can expand youth access to all kinds of resources.

MC: The design of hybrid programs must be carefully considered in order for programs to, as one of our participants said, “bring the activity, energy and vibe that instructors bring to class to the virtual format.” As Tracey says, you have to carefully consider the work that's being done and determine which activities could be suited for the virtual space. Also remember that you can’t just be in one social space or one app. You have to meet students where they are and that’s always going to be shifting.

Most importantly, anytime you're doing programming that supports young people, young artists, they need to be brought into the design. I am really hyped about how our Type Beat challenge did that. It meant a lot to our young people, particularly in the moment in time that we were in, for them to have that agency, to feel that power and feel like they would produce not only the music but they would produce this program that is now living on.

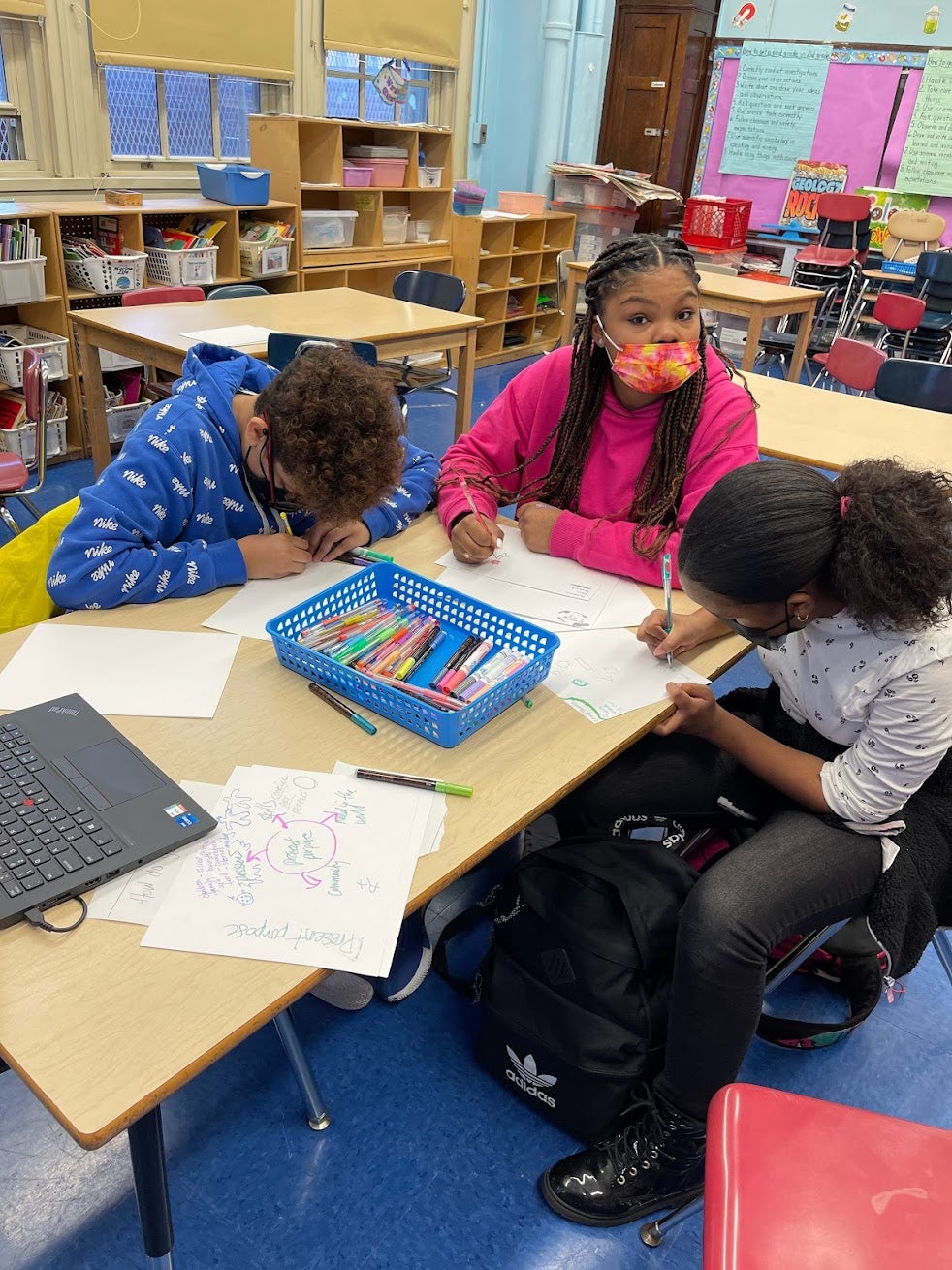

All photos courtesy of the Boys & Girls Club of America and YR Media.

Lead photo courtesy of YR Media, featuring Oliver "Kuya" Rodriguez, music and audio production program manager, who ran the Type Beat Challenge.