Despite decades of standards-based reforms, states continue to struggle with finding ways to turn around low-performing schools and districts. States encounter barriers at all levels of the system to implementing coherent responses to the growing number of schools that are chronically failing to meet performance requirements.

It is estimated that by 2010, about five percent of the nation’s public schools, many of them in high-poverty areas, will have moved into the most extreme NCLB designation—one that calls for school restructuring. In some states, the figure approaches 50 percent of public schools. The sheer scale of the ongoing challenges—which now include significant recession-related belt-tightening for urban schools that already tend to have fewer resources and less experienced and less qualified teachers than schools in more affluent communities—and what is needed to overcome them have raised a host of issues about how states can create a viable strategy and the capacity to turn around low performing schools.

While a great deal is known about the key elements associated with effective schools, much less is known about how to successfully implement improvement strategies across large numbers of schools serving high- poverty, highly challenged students. But one thing is clear: the vast majority of our urban public education systems have been unable to bring even half their students to proficiency in academics and readiness for college. These districts account for about 25 percent of dropouts in the nation and pose one of the gravest social inequities of our time. A recent report from McKinsey and Company on the economic impact of the achievement gap states that “the persistence of these educational achievement gaps imposes on the United States the economic equivalent of a permanent national recession.” 1

In another report, researchers at Johns Hopkins University identified about 2,000 high schools as “dropout factories” that produce 69 percent of all African American dropouts and 63 percent of all Hispanic dropouts. 2 What’s even more troubling is that the gap between students from rich and poor families on measures of educational attainment is much more pronounced in the United States than in other high- performing nations around the world. In other words, the United States fares poorly on a key indicator of equal opportunity in a society: the degree to which economic status predicts student achievement. By every measure of educational achievement, poor and minority students in this country fare worse than their other American and international peers.

In March 2009, the National Association of State Boards of Education (NASBE) and the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) invited Andy Calkins from the Mass Insight Education and Research Institute and Sam Redding from the National Center on Innovation and Improvement to address state board of education chairs and chief state school officers on designing a coherent strategy to turn around the lowest-performing schools. Executive directors from NASBE and CCSSO—Brenda Welburn and Gene Wilhoit—opened the dialogue by setting the context for state efforts to turn around low POLICY UPDATE Vol. 17, No. 7 Special Edition June 2009 State Strategies for Turning Around Low-Performing Schools and Districts A Study Guide for Policymakers Based on a Symposium for State Board Chairs and Chief State School Officers by Dr. Mariana Haynes performing schools in terms of the opportunity afforded through the Obama administration’s priority areas for federal stimulus funds under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA).3

As public pressure for states to effect change in underperforming schools continues to increase, there is broad recognition that states must adopt a more active, strategic role than they’ve had before. State approaches must move beyond convenience to focus on addressing the underlying causes of schools’ inability to meet performance requirements. Welburn and Wilhoit emphasized that ultimately states would be accountable for the impact of stimulus spending and cautioned state leaders to think carefully about the complex factors that impact turnaround initiatives. In setting the broad parameters for turnaround strategies, they called for states to:

- Create a framework for school and district intervention based on research and best practice and develop transparent policy and agency procedures that can be used to drive improvement across all schools (e.g., through audits, accreditation processes, and procedures);

- Use longitudinal data systems to monitor student achievement in content areas and by subgroups, identify the degree of intervention and support needed, and design a system that incorporates multiple tiers or levels that diff er in their nature and intensity;

- Create a set of strategies that leverage resources and consequences in order to impel districts to act independently to make improvements before the state has to intervene to restructure;

- Provide human and fiscal resources to support turnaround work by developing cadres of specialists, partners, and teams (e.g., the Virginia School Turnaround Specialist Program and the Kentucky Distinguished Educator Program);

- Implement radically improved management structures and processes and use community partnerships and services to transform the most chronically underperforming districts and schools serving the most challenged students.

This brief outlines the major themes discussed throughout the symposium for chiefs and state board chairs, outlines the Mass Insight turnaround framework, and provides sets of questions states need to consider in creating innovative solutions for low-performing schools that can inform large-scale improvement in education.

Leading off the conversation about how to frame a coherent response to high-needs schools, Andy Calkins outlined a number of critical distinctions and constructs that states need to consider to create effective solutions.4 His remarks were based on the Mass Insight Education and Research Institute’s report on The Turnaround Challenge. The report chronicles shortcomings in states’ “light touch” efforts that focus largely on programmatic and curricular changes and proposes an alternate framework for producing dramatic, transformative change in the lowest-performing schools.5 Calkins called for strong political leadership and commitment in order to design scalable and sustainable improvements, change conditions and incentives, and strengthen the systems states establish to train and support teachers and school leaders. Moreover, he challenged states to generate solutions with the broader purpose of integrating evidence-based elements for turnaround initiatives into systemic improvement efforts for all schools.

Theme 1: Understand The Elements That Serve Challenged Students Well

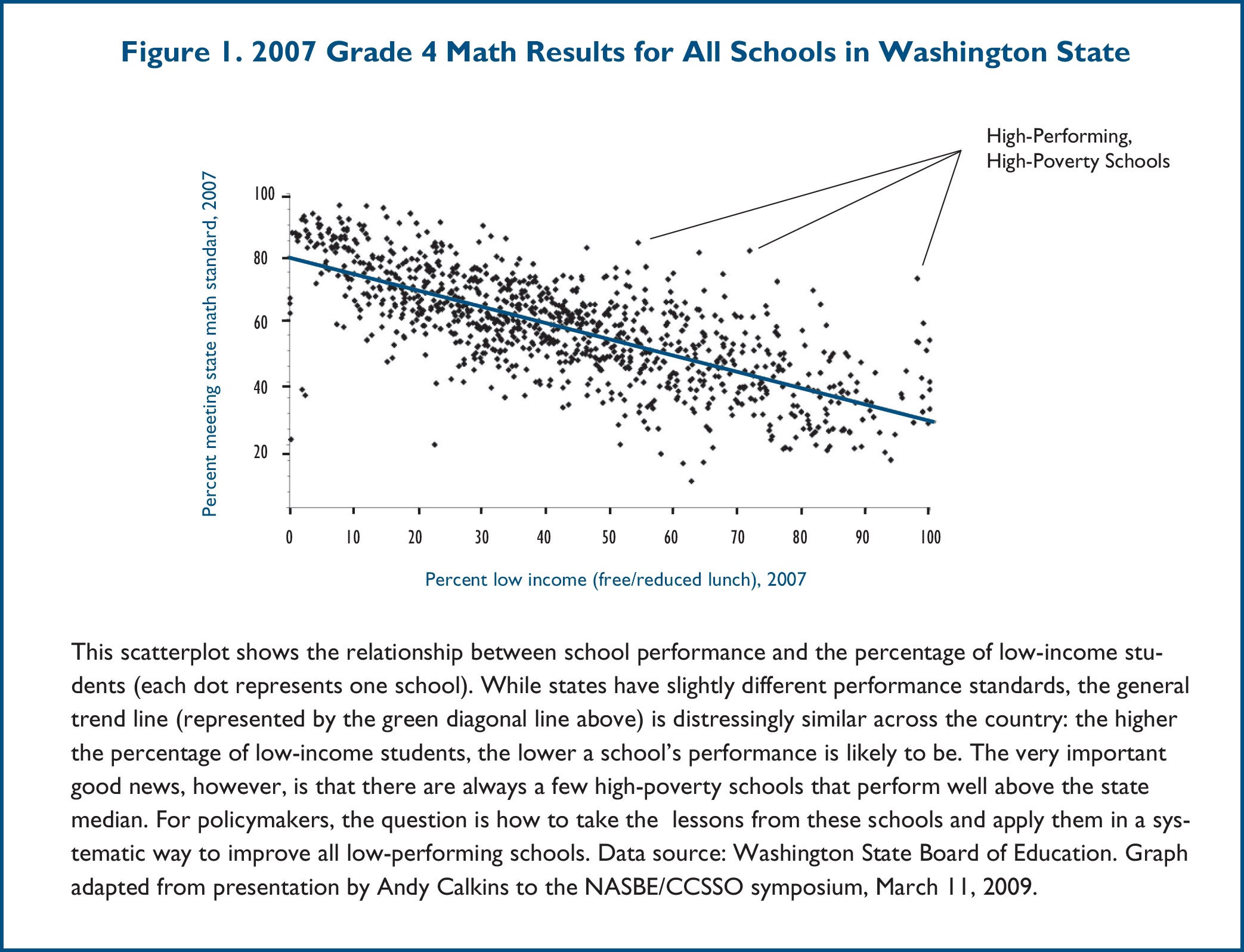

Calkins noted that consistent patterns of performance can be seen in all states that show a strong correlation between poverty and chronic under-performance, with the most severe performance deficits seen in schools with over 50 percent poverty. He shared data scatterplots from a number of states that depict the negative relationship between poverty and achievement: as the number of students in poverty increases even by a small degree within schools, achievement declines (see example in fi g. 1 on page 3). Yet, the data reveals that while dramatic variability is observed in high-poverty schools (those with over 50 percent poverty) and that the majority perform at dire levels, a small number of schools “beat the odds,” performing above the state median and proving that poverty and race are not destiny for low academic attainment.

Calkins said that the good news is that all states have a handful of these high-performing, high-poverty (HPHP) schools that can serve as a “new-world” model of schooling and as an opportunity to understand and replicate the hallmarks of what contributes to their success. Based on an extensive review of research from a number of fi elds, Calkins and his fellow researchers attributed the high-level performance to a major shift in organizational mission that moved these schools from the traditional conveyor belt, teaching-driven model (what’s taught) to a student-centered, learning-driven model (what’s learned). “Schools do not achieve high performance by doing one or two things differently—they must do a number of things differently, and all at the same time, to begin to achieve the critical mass that will make a difference in student outcomes,” Calkins said. "In other words, high-poverty schools that achieve gains in student performance engage in systemic change.” 6

So how do we understand what those schools actually do that sets them apart? The attributes of HPHP schools have been incorporated into Mass Insight’s “Readiness” Model. Th is framework delineates a set of conditions, capacities, and attributes essential to organizing schools around a deep commitment to meeting the individual needs of every learner. HPHP schools differ appreciably from others in their willingness to take on the concerns and challenges facing highly challenged, high-poverty students. What’s striking about these schools is their overriding mission to serve students and make decisions in their best interest, as opposed to responding to structures, contracts, and schedules that pose barriers to responding to the needs of individual learners.

Key Characteristics of High-Performing, High-Poverty Schools

Readiness to Learn

- Safety, Discipline, and Engagement: Students feel secure and inspired to learn

- Action Against Adversity: Schools directly address their students’ poverty-driven deficits

- Close Student-Adult Relationships: Students have positive and enduring mentor/teacher

relationships

Readiness to Teach

- Shared Responsibility for Achievement: Staff feels deep accountability and a missionary

zeal for student achievement - Personalization of Instruction: Individualized teaching based on diagnostic assessment

and adjustable time on task - Professional Teaching Culture: Continuous improvement through collaboration and job embedded learning

Readiness to Act

- Resource Authority: School leaders can make mission-driven decisions regarding people,

time, money, and program - Resource Ingenuity: Leaders are adept at securing additional resources and leveraging

partner relationships - Agility in the Face of Turbulence: Leaders, teachers, and systems are flexible and

inventive in responding to constant unrest

Source: The Turnaround Challenge: Why America’s Best Opportunity to Dramatically Improve Student Achievement Lies in Our Worst-performing Schools, Mass Insight Education and Research Institute. Mass Insight Education and Research Institute

The model includes nine elements identified as attributes of HPHP schools (see textbox above).

The question for state boards and chiefs, of course, is how can states replicate the model HPHPs and create programs for underperforming schools in the context of a broader state system of supports and interventions? What’s often missed is that, although many of the barriers and conditions that impede major improvements also operate in higher-income communities, the limitations of the system and their impact on more affluent student groups are obscured. As the bar has risen for all students to achieve at higher levels of college and career readiness, states will need to consider how to scale the HPHP practices highlighted in the Mass Insight Readiness Model: their ability to cultivate shared responsibility for achievement among individuals throughout the system, the use of frequent assessment to personalize instruction, and the focus on the cultivation of a professional, collaborative teaching culture.

Theme 1 Questions for State Leaders

- What have you learned from high-performing, high-poverty (HPHP) schools in your state?

- Does your state recognize that a turnaround strategy for failing schools requires fundamental changes that are different from an incremental improvement strategy?

- What is the opportunity represented by struggling schools? How can your state replicate a model of HPHP schools and integrate key elements into the broader system?

- How can a state build and leverage local support for a turnaround effort that catalyzes genuine change (and will therefore ruffle some feathers)? What are effective tactics that can reduce opposition (from communities, local school boards, schools, and policy/legislative leaders) to transformative intervention strategies?

- What are the respective roles for state boards, governors, and state education chiefs in leading the way on school turnaround?

Theme 2: Confronting Barriers and Building Capacity

How can we organize ourselves to ask the right questions and transform how we work in schools that serve challenging students? What’s stopping us from applying the lessons from HPHP schools and scaling effective practice throughout the broader system? Calkins cautioned state leaders about the pitfalls of reform strategies that do little more than add a new program or provide some minimal coaching and training. State efforts and capacity to turn around schools run headlong into longstanding concerns about the fundamental assumptions and impact of standards- based reform. State reform has set instructional goals in terms of student outcomes or achievement levels rather than in terms of what schools do to help students achieve.

Moreover, moving beyond standard approaches to intervening in low-performing schools requires grappling with consistent barriers that undercut the impact of school reform initiatives. Studies point to insufficient and unstable resources, insufficient time for professional development and teacher collaboration, inflexibility in allocating resources to higher need areas, lack of coherent systems to recruit, develop, and retain quality educators, and the need for program coherence among state education agencies.

Why has so little fundamental change occurred nationally in failing schools to date? One answer is that most school reform shows up in schools—even in those schools that have persistently failed—as fairly disconnected, incremental improvement projects that do not adequately address root causes. Scaling up what works and leading systemic change are inherently difficult because they require changing the behavior of all individuals at every level of the system. Ultimately, improving school performance requires significant improvements at the classroom level in the quality of instructional practice and the level of student engagement, learning, and performance. But this calls for schools to make mission-driven decisions in accord with students’ needs— and hence, truly comprehensive, transformational reform challenges conventional structures, processes, and “turf.” Unfortunately, an array of political forces, funding problems, and turnover in school and district leadership have contributed to a lack of sustained focus and the current paucity of successful turnaround models.

The state educational officials participating in the symposium concurred on two major obstacles impeding effective turnaround efforts: first, the lack of human capacity—the system does not have the people needed to produce universal high-quality schools, and second, operating conditions—the system doesn’t allow its primary organizations to work effectively or motivate the people in them to do their best work. Th e implications are that states will need to pilot new comprehensive approaches that include changes in the way states work within the state agency and with districts and schools. To that end, education and policy leaders will need to create greater program coherence at all levels of the system, secure permanence in funding for programs, identify mechanisms to increase operating flexibility and autonomy, and redesign systems that support the entry, development, and retention of quality teachers and school leaders.

Calkins and Redding7 urged states to have hard conversations about what’s at stake, the role of key political leaders, how to leverage improvements, build sufficient capacity, and create models that help defi ne what success will look like. Of critical importance is the notion of reciprocal accountability that must operate at each level so that the roles and responsibilities of key players enhance the capacity and performance of others—from the state through the districts to the schools and students. Th e state must do everything possible to reduce the barriers that impede mission-driven decisions and use incentives as well as accountability measures to get districts to turn around their lowest performing schools. Such eff orts require leading change at all levels to create a culture of continuous improvement that shifts from compliance to a service mode on the part of all entities. States need to consider how to create organizational structures to coordinate action across divisions within the state agency, increase coherence and alignment in leveraging expertise and resources, and build an infrastructure for developing and providing intervention and support customized to meet the local context.8

Finally, capacity for turnaround work rests with the caliber of people in the system. States must commit to addressing the longstanding problems with their systems for recruiting, preparing, supporting, and evaluating teachers and school leaders. Programs for preparing educators, for example, continue to be driven by what providers want to off er—not by what schools or staff need; and licensure remains poorly connected to how well educators impact student achievement and school performance. Studies show that the training principals receive across the nation leaves the majority ill-equipped for the job of promoting powerful teaching and learning, particularly with those students who need it the most. A national study of 31 preparation programs by Hess and Kelly found a critical lack of emphasis on results-oriented management and accountability, hiring quality teachers, making personnel decisions on the basis of performance, or using data or technology to manage school improvement.9 In like fashion, more than two-thirds of teachers in the United States reported that they had not even had one day of training during the previous three years in how to support the learning of special education or LEP students.10

Theme 2 Questions for State Leaders

- How can changing organizational structures within the state help districts and schools address the

challenge of chronically low-performing schools? - What organizational issues need to be addressed? What would be the best possible state structure

for leading a turnaround effort (e.g., turnaround zone, new SEA division, P-16 subcommittee, quasiindependent

state authority, other)? Who would it include and how would it be funded? - Does your state recognize that turnaround success depends primarily on an effective people strategy that recruits, develops, and retains strong leadership teams and teachers?

- Does your state provide sufficient incentives in pay and working conditions to attract the best possible staff and encourage them to do their best work?

- Does your state’s turnaround strategy provide school-level leaders with sufficient

Washington State’s Guiding Principles for the Design of Turnaround Strategy

In 2006, the Washington State legislature charged the Washington State Board of Education with developing a statewide accountability system that identifies “schools and districts which are successful, in need of assistance, and those where students persistently fail [and where]…improvement measures and appropriate strategies are needed.” The legislature also asked the state board to develop a statewide strategy to help the challenged schools improve. Washington contracted with Boston-based Mass Insight Education and Research Institute and Seattle-based Education First Consulting to assist the state board in developing the plan for state and local partnerships to help Washington’s lowest performing schools improve.

This team convened a broad range of stakeholders in Washington to deliberate on what can be done for the schools in highest need, called Priority Schools. The goal was to prepare recommendations and proposals for the 2009 legislative session, as well as for the state’s Joint Basic Education Funding Task Force. While the recommendations specifically focus on strategies to help the most challenged schools, they link with the state’s larger accountability system and assistance plans for all schools.

The proposed plan frames a new kind of state and local partnership in standards-based reform for Washington State. It grew directly out of a set of “guiding principles” developed by the project’s design team, which was composed of more than 20 key stakeholder leaders. Based on an examination of the research on barriers to school improvement (both in-state and nationally), as well as on extensive conversations with various stakeholders, the state board and the design team developed general consensus around a set of guiding principles for turnaround in Washington State:

The Seven Guiding Principles

- The initiative is driven by one mission: student success. Whatever the reason, most students are not succeeding in Priority Schools. This initiative is our chance to show that they can—and how they can—so other schools can follow.

- The solution we develop is collective. Every stakeholder may not agree with every strategy; aspects of the solution may call for new thinking and new roles for all participants. But this challenge requires proactive involvement from all of us.

- There is reciprocal accountability among all stakeholders. This challenge needs a comprehensive solution that distributes accountability across the key stakeholders: the state, districts, professional associations, schools, and community leaders.

- To have meaning, reciprocal accountability is backed by reciprocal consequences. Everyone lives up to their end of the agreement, or consequences ensue.

- The solution directly addresses the barriers to reform. As identified by Washington State stakeholders, these include inadequate resources; inflexible operating conditions; insufficient capacity; and not enough time.

- The solution requires a sustained commitment. That includes sufficient time for planning, two years to demonstrate significant improvement (i.e., leaving the Priority Schools list), and two more years to show sustained growth.

- The solution requires absolute clarity on roles—for the state and all of its branches, districts, schools, and partners.

Source: Serving Every Child Well: Washington State’s Commitment to Help Challenged Schools Succeed. Final Report to the Washington State Board of Education (Boston, MA: Mass Insight Education and Research Institute, December 2008).

Theme 3: Creating a “Turnaround Zone”

Calkins spoke of the need to change the systemic conditions that actively shape how everyone behaves in schools. He noted there is evidence that leaders of HPHP schools succeed largely by circumventing the most dysfunctional obstacles presented by the system. In order to foster this kind of behavior in more low-performing schools, Calkins recommended clustering schools (organized around a common attribute such as school type, reform approach, or feeder pattern) into Turnaround Zones. Within such zones, school leaders are given

- Staffing—including more authority over hiring, placement, compensation, and work rules;

- Scheduling—including longer school days, longer year, or year-round school calendar;

- Funding—including both more resources and more budgeting flexibility;

- School program—including more authority to design the program to specifically fit the needs of the school’s students, both academically and psycho-socially; and

- Leadership—within this framework, districts need to establish professional norms for strategic human capital initiatives that focus on developing the capacity of school leadership teams to lead school turnaround. In addition to designing systems for attracting and retaining quality teachers and leaders, capacity-building hinges on creating networks and partnerships with entities that can provide turnaround expertise.

A number a big-city districts, including Chicago, New Orleans, New York City, and Philadelphia, have been experimenting with Turnaround Zones for several years. Th e idea is to enable local leaders to earn the opportunity to turn around schools in partnership with the state and through what Calkins called “the three C’s”: changing conditions, capacity, and clustering.

The core strategies include crafting a carrot and stick approach, creating differentiated levels of intervention in districts based on the degree of need, and balancing flexibility and autonomy for districts to leverage their willingness to change prior to losing control to the state under the final NCLB designation—reconstitution.

Districts can opt into a partnership with the state and receive resources and other supports in exchange for meeting specific criteria and benchmarks. It is essential to provide countervailing incentives to generate bold action that differs from the standard approaches taken by states to intervene in low-performing schools. Strong interventions are rare because they tend to confront established interests and state and district constraints. In other words, the state must carefully balance the degree of autonomy over operating conditions (time, people, money, and resources) with the accountability for making progress within an agreed upon timeframe. Th e goal is to reduce the compliance burden and redirect how decisions are made in accord with student interests and the mission of the school. Th e state reserves the final option to change governance and intervene if insufficient progress is made, but the intent is to give districts the incentive to opt into a self-designed turnaround strategy before restructuring or reconstitution is needed.

Theme 3 Questions for State Leaders

- Within the protected Turnaround Zones, does your state collaborate with districts to organize turnaround work into school clusters (by need, school type, region)?

- How can schools be clustered so reforms can expand systemically, not just taking place in one school at a time?

- Does your state have a strategy to develop lead partner organizations with specific expertise needed to provide intensive school turnaround support?

- What’s needed to leverage innovation and improvements at the district level to serve, high-poverty students?

- What models already exist in the state that turnaround efforts can build on? These could include charter, pilot, alternative, or other schools that set aside some normal operating structures in order to give leaders more freedom to allocate people, time, money, and programs according to their students’ needs.

State Panel on Turnaround Efforts in Massachusetts and Maryland

Following the session with Andy Calkins, panelists from Massachusetts and Maryland off ered insights and examples of how their states were moving beyond traditional school improvement eff orts to connect and align major reform strategies at the state, district, and school levels. Th e panel was moderated by Richard Laine, Director of Education Programs at Th e Wallace Foundation, who framed the discussion by emphasizing that we know a great deal about what it takes to turn around schools, but lack the political will to apply the necessary levers to build capacity, allocate resources, and alter operating conditions. Laine asked the states about their efforts to build capacity at all levels of the system in order to ensure strong implementation and sustainability of turnaround interventions and strategies.

Massachusetts

Maura Banta, chair of the Massachusetts State Board of Education and Mitchell Chester, state Commissioner of Education, outlined the evolution of their state-level district audit system, which is conducted under the auspices of an independent agency, the Education Quality Administration Office. Over time, the state created a process to integrate accountability with the assistance and intervention functions provided through the state education department, focusing on the district as the point of entry and as the essential unit to scale and sustain turnaround eff orts. Th e resulting framework created five graduated levels of intervention for districts, depending on the seriousness of their need for corrective action. Th e greatest number of districts fall into the first designation and receive access to planning tools and resources based on the “Ten Essential Conditions” for improving teaching and learning, adopted in October 2006 and which form the basis of the state’s turnaround strategy (see https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED538300.pdf).

- The school’s principal has authority to select and assign staff to positions in the school without regard to seniority;

- The school’s principal has control over financial resources necessary to successfully implement the school improvement plan;

- The school is implementing curricula that are aligned to state frameworks in core academic subjects;

- The school systematically implements a program of interim assessments (four to six times per year) in English language arts and mathematics that are aligned to the school curriculum and state frameworks;

- The school has a system to provide detailed tracking and analysis of assessment results and uses those results to inform curriculum, instruction, and individual interventions;

- The school schedule for student learning provides adequate time on a daily and weekly basis for the delivery of instruction and provision of individualized support as needed in English language arts and math. For students not yet proficient, support is presumed to be at least 90 minutes per day in each subject;

- The school provides daily after-school tutoring and homework help for students who need supplemental instruction and focused work on skill development;

- The school has a least two full-time subject-area coaches, one each for English language arts/reading and for mathematics, who are responsible to provide faculty at the school with consistent classroom observation and feedback on the quality and effectiveness of curriculum delivery, instructional practice, and data use;

- School administrators periodically evaluate faculty, including direct evaluation of applicable content knowledge and annual evaluation of overall performance tied in part to solid growth in student learning and commitment to the school’s culture, educational model, and improvement strategy; and

- The weekly and annual work schedule for teachers provides adequate time for regular, frequent, department and/or grade-level faculty meetings to discuss individual student progress, curriculum issues, instructional practice, and school-wide improvement eff orts. As a general rule, no less than one hour per week should be dedicated to leadership-directed, collaborative work, and no fewer than five days per year (or equivalent hours) when teachers are not responsible for supervising or teaching students, will be dedicated to professional development and planning activities directed by school leaders.

The most severe designation for districts—chronic underperformance—applies to only a handful in the state and requires tighter regulation in the form of cogovernance and joint decision-making between the state and district. In order to motivate districts to act independently and preempt a state takeover, districts have the opportunity to use tools to identify root causes, develop a recovery plan with state guidance and oversight, and receive resources and support to make progress in meeting benchmarks.

Chester emphasized the following points about leading change at the state level:

- Create strategies that differentiate need and level of intervention and supports;

- Build district capacity and expertise;

- Rely on partners to expand work across regions; and

- Exercise the power of the state to leverage attention, resources, and partnerships to mobilize efforts and sustain progress.

Maryland

Robert Glascock, the Executive Director of the Breakthrough Center in the Maryland State Department of Education (MSDE), described his state’s efforts to work with districts on turnaround strategies, broker a range of services and resources in education, business, government, and research centers; and create cross-district and cross-sector networks. The Breakthrough Center represents a shift for the MSDE from compliance monitoring to providing strategic direction and services as part of a differentiated accountability system. Glascock outlined the core principles emanating from the Maryland Commission on Education Finance, Equity, and Excellence (known as the Thornton Commission after its chairman, Alvin Thornton).

In 2002, the General Assembly enacted the Bridge to Excellence in Public Schools Act, based substantially on the recommendations of the Thornton Commission. The act sought to increase state funding for public education and to ensure that school systems have adequate resources to meet student performance standards while providing maximum local flexibility for the systems to allocate resources. The Act significantly enhanced local school system accountability for student performance by requiring all local school systems to develop a five-year comprehensive master plan for student achievement. The Act increased per pupil funding across the board and eliminated numerous categorical programs in favor of providing additional per pupil funding for students with special needs (including special education students, those with limited English proficiency, and those suffering from economic disadvantage).

Consistent with enhancing adequacy, equity, and flexibility to advance education, Glascock emphasized increasing the services and supports needed to meet the unique and emerging needs of Maryland districts. Key functions of the Breakthrough Center include:

- Developing greater coherence and customization of services and solutions for districts and schools;

- Eliminating the overlap between services and programs delivered by various divisions within the state agency;

- Providing strategies to ensure high-capacity teaching and a personalized learning environment for students;

- Clarifying and formalizing the criteria for district participation and level of involvement; and

- Establishing uniform standards of quality to measure the impact of these services.

As the number of schools in improvement increased under the No Child Left Behind Act, Maryland sought new ways of working to focus strategically on: 1) how to build sustainability of improvement and 2) how to provide more uniquely tailored strategies for improvement. Maryland applied for and received permission from the U.S. Department of Education to pilot a differentiated accountability system. Accordingly, the Breakthrough Center began providing two categories of support services: Buildup Services—targeted primarily for districts and schools in the “Comprehensive” category of improvement and available to those in the “Alert” status to prevent progression into the more severe categories of improvement; and Access Services—available to all districts and schools and required for those in the “Focus” category of school improvement (see www.ed.gov/admins/lead/account/differentiatedaccountability/mdexsum.doc.).

According to Glascock, the central elements of a successful turnaround strategy should include clustering of schools as part of a turnaround zone within and across districts; using technology and data to communicate across networks; and increasing coherence in state-level guidance, program requirements (e.g., special education, Title I), and funding.

More Questions for State Leaders

- How has the state integrated accountability and technical assistance?

- How can the state leverage a coordinated response from districts at all levels to preempt the need for state intervention and ultimately restructuring?

- What resources, partnerships, and tools are available to help all districts proactively implement well-designed improvement strategies?

- How can your state build district capacity to sustain improvements following the infusion of resources, funds, and technical assistance?

State Levers for Improving Priority Schools and Districts

Finally, in response to Richard Laine’s question about how states identify and align key levers to mobilize innovation and improvements in priority districts and schools, the panelists identified a number of leverage points:

- Increasing coherence by ensuring that policy and program elements are integrated and sustained to maximize efficiencies, transparency, and impact;

- Refocusing attention on the learner as a way to begin working across multiple systems (e.g., health, juvenile justice, social services) and coordinating eff orts to address impacts on challenged populations (e.g., dropouts, English language learners);

- Developing regional and collaborative structures to create networks, expertise, and resources that expand capacity to scale effective practices and strategies;

- Clustering districts that have been unsuccessful in significantly improving schools in order to pool resources, strategies, and personnel around a common agenda;

- Identifying the tools and operating conditions needed for turnaround work and integrating resource elements such as human resource departments, IT, and purchasing toward turnaround goals;

- Balancing flexibility and autonomy based on the local context to accelerate change and apply what’s worked to inform broader systems design; and

- Addressing union contracts so that the state, district, and teachers are working in tandem toward the goal of ameliorating the circumstances of low performance.

Conclusion

Throughout the symposium, the participants were challenged to think about three broad areas in considering effective turnaround strategies: 1) the political and communication dimensions of a school turnaround effort; 2) reorganizing state structures, policies, and processes; and 3) building capacity for turnaround efforts. States examined a range of issues that drive the level of commitment and capacity to pioneer new approaches to longstanding challenges in reducing enormous gaps in student attainment. A number of other themes surfaced, including the importance of honest and open discussion about the level of commitment to adopting comprehensive turnaround strategies; the need for greater coherence among board policies, agency procedures, and guidance to districts and schools; creating a culture of mutual accountability for mission-driven policy development and decision-making; expanding expertise and capacity through strategic use of networks, regional centers, partnerships, and technology; establishing a cycle of continuous evaluation and refinement to scale what works and maximize efficiencies; and building a human capital system to ensure that highly effective teachers and school leaders serve in our most challenged schools.

Foremost, state board members and state education chiefs recognized the critical window of opportunity afforded in the current political and economic environment. They gave voice to the growing sense of urgency to grapple with longstanding issues about disparities in education opportunity for different student groups and to respond to the challenges to prepare a highly educated workforce for America’s 21st century. They discussed the ramifications and opportunities proffered by the federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act and how stimulus funds could be used to enhance system and human capacities to accelerate reforms in public education, particularly in the lowest-performing schools.

Finally, there was agreement that now is the time to chart a viable state role in providing supports and interventions to meet the needs of highly challenged students in the run up to the reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act.

Endnotes

1 McKinsey and Company, Social Sector Office, The Economic Impact of the Achievement Gap in America’s Schools (McKinsey and Company, 2009).

2 National Governors Association, Council of Chief State School Officers, and Achieve, Inc., Benchmarking for Success: Ensuring U.S. Students Receive a World-Class Education (Washington, DC: International Benchmarking Advisory Group, December 2008).

3 Available online at www.ed.gov/policy/gen/leg/recovery/index.html.

4 Andy Calkins was formerly the Senior Vice President of Mass Insight Education and Research Insight and is currently the Senior Program Officer of the Learning Community Efficacy Network of the Stupski Foundation.

5 A. Calkins, W. Guenther, G. Belfi ore, and D. Lash, The Turnaround Challenge: Why America’s Best Opportunity To Dramatically Improve Student Achievement Lies In Our Worst-Performing Schools (Boston, MA: Mass Insight Education and Research Institute, 2007). Available online at www.massinsight.org/resourcefiles/TheTurnaroundChallenge_2007.pdf.

6 Ibid.

7 Sam Redding is Executive Director, Academic Development Institute and Director, National Center on Innovation and Improvement.

8 M. Haynes, Building the Capacity of State Education Agencies to Support Schools (Arlington, VA: National Association of State Boards of Education, February 2009).

9 F. M. Hess and A. P. Kelly, Learning to Lead? What Gets Taught in Principal Preparation Programs (Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute, 2005).

10 L. Darling-Hammond, R.C. Wei, A. Andree, N. Richardson, and S. Orphanos, Professional Learning in the Learning Profession: A Status Report on Teacher Development in the United States and Abroad (Palo Alto, CA: National Staff Development Council and The School Redesign Network at Stanford University, 2009).

Policy Updates are developed and produced by the National Association of State Boards of Education, 2121 Crystal Drive, Suite 350, Arlington, Virginia 22202. 703-684-4000, www.nasbe.org. For more information about this topic and other school leadership issues, contact Dr. Mariana Haynes at marianah@nasbe.org.

This Policy Update was produced with support from The Wallace Foundation.

Key Characteristics of High-Performing, High-Poverty Schools

Readiness to Learn

- Safety, Discipline, and Engagement: Students feel secure and inspired to learn

- Action Against Adversity: Schools directly address their students’ poverty-driven deficits

- Close Student-Adult Relationships: Students have positive and enduring mentor/teacher

relationships

Readiness to Teach

- Shared Responsibility for Achievement: Staff feels deep accountability and a missionary

zeal for student achievement - Personalization of Instruction: Individualized teaching based on diagnostic assessment

and adjustable time on task - Professional Teaching Culture: Continuous improvement through collaboration and job embedded learning

Readiness to Act

- Resource Authority: School leaders can make mission-driven decisions regarding people,

time, money, and program - Resource Ingenuity: Leaders are adept at securing additional resources and leveraging

partner relationships - Agility in the Face of Turbulence: Leaders, teachers, and systems are flexible and

inventive in responding to constant unrest

Source: The Turnaround Challenge: Why America’s Best Opportunity to Dramatically Improve Student Achievement Lies in Our Worst-performing Schools, Mass Insight Education and Research Institute. Mass Insight Education and Research Institute

Readiness to Learn

Safety, Discipline, and Engagement: Students feel secure and inspired to learnAction Against Adversity: Schools directly address their students’ poverty-driven deficitsClose Student-Adult Relationships: Students have positive and enduring mentor/teacher relationships Source: The Turnaround Challenge: Why America’s Best Opportunity to Dramatically Improve Student Achievement Lies in Our Worst-performing Schools, Mass Insight Education and Research Institute. Mass Insight Education and Research Institute

Readiness to Teach

Shared Responsibility for Achievement: Staff feels deep accountability and a missionary zeal for student achievementPersonalization of Instruction: Individualized teaching based on diagnostic assessment and adjustable time on taskProfessional Teaching Culture: Continuous improvement through collaboration and job embedded learning

Readiness to Act

Resource Authority: School leaders can make mission-driven decisions regarding people, time, money, and programResource Ingenuity: Leaders are adept at securing additional resources and leveraging partner relationshipsAgility in the Face of Turbulence: Leaders, teachers, and systems are flexible and inventive in responding to constant unrest