State Strategies for Turning Around Low-Performing Schools and Districts

Despite decades of standards-based reforms, states continue to struggle with finding ways to turn around low-performing schools and districts. States encounter barriers at all levels of the system to implementing coherent responses to the growing number of schools that are chronically failing to meet performance requirements. It is estimated that by 2010, about five percent of the nation’s public schools, many of them in high-poverty areas, will have moved into the most extreme NCLB designation—one that calls for school restructuring. In some states, the figure approaches 50 percent of public schools. The sheer scale of the ongoing challenges—which now include significant recession related belt-tightening for urban schools that already tend to have fewer resources and less experienced and less qualified teachers than schools in more affluent communities—and what is needed to overcome them have raised a host of issues about how states can create a viable strategy and the capacity to turn around low performing schools.

While a great deal is known about the key elements associated with effective schools, much less is known about how to successfully implement improvement strategies across large numbers of schools serving high poverty, highly challenged students. But one thing is clear: the vast majority of our urban public education systems have been unable to bring even half their students to proficiency in academics and readiness for college. These districts account for about 25 percent of dropouts in the nation and pose one of the gravest social inequities of our time. A recent report from McKinsey and Company on the economic impact of the achievement gap states that “the persistence of these educational achievement gaps imposes on the United States the economic equivalent of a permanent national recession.”[1] In another report, researchers at Johns Hopkins University identified about 2,000 high schools as “dropout factories” that produce 69 percent of all African American dropouts and 63 percent of all Hispanic dropouts.[2] What’s even more troubling is that the gap between students from rich and poor families on measures of educational attainment is much more pronounced in the United States than in other high performing nations around the world. In other words, the United States fares poorly on a key indicator of equal opportunity in a society: the degree to which economic status predicts student achievement. By every measure of educational achievement, poor and minority students in this country fare worse than their other American and international peers.

In March 2009, the National Association of State Boards of Education (NASBE) and the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) invited Andy Calkins from the Mass Insight Education and Research Institute and Sam Redding from the National Center on Innovation and Improvement to address state board of education chairs and chief state school officers on designing a coherent strategy to turn around the lowest-performing schools. Executive directors from NASBE and CCSSO—Brenda Welburn and Gene Wilhoit—opened the dialogue by setting the context for state eff orts to turn around low performing schools in terms of the opportunity afforded through the Obama administration’s priority areas for federal stimulus funds under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA).[3] As public pressure for states to effect change in underperforming schools continues to increase, there is broad recognition that states must adopt a more active, strategic role than they’ve had before. State approaches must move beyond convenience to focus on addressing the underlying causes of schools’ inability to meet performance requirements. Welburn and Wilhoit emphasized that ultimately states would be accountable for the impact of stimulus spending and cautioned state leaders to think carefully about the complex factors that impact turnaround initiatives. In setting the broad parameters for turnaround strategies, they called for states to:

- Create a framework for school and district intervention based on research and best practice and develop transparent policy and agency procedures that can be used to drive improvement across all schools (e.g., through audits, accreditation processes, and procedures);

- Use longitudinal data systems to monitor student achievement in content areas and by subgroups, identify the degree of intervention and support needed, and design a system that incorporates multiple tiers or levels that diff er in their nature and intensity;

- Create a set of strategies that leverage resources and consequences in order to impel districts to act independently to make improvements before the state has to intervene to restructure;

- Provide human and fiscal resources to support turnaround work by developing cadres of specialists, partners, and teams (e.g., the Virginia School Turnaround Specialist Program and the Kentucky Distinguished Educator Program); and

- Implement radically improved management structures and processes and use community partnerships and services to transform the most chronically underperforming districts and schools serving the most challenged students.

This brief outlines the major themes discussed throughout the symposium for chiefs and state board chairs, outlines the Mass Insight turnaround framework, and provides sets of questions states need to consider in creating innovative solutions for low-performing schools that can inform large-scale improvement in education.

Leading off the conversation about how to frame a coherent response to high-needs schools, Andy Calkins outlined a number of critical distinctions and constructs that states need to consider to create effective solutions.[4] His remarks were based on the Mass Insight Education and Research Institute’s report on The Turnaround Challenge.* The report chronicles shortcomings in states’ “light touch” eff orts that focus largely on programmatic and curricular changes and proposes an alternate framework for producing dramatic, transformative change in the lowest-performing schools.[5] Calkins called for strong political leadership and commitment in order to design scalable and sustainable improvements, change conditions and incentives, and strengthen the systems states establish to train and support teachers and school leaders. Moreover, he challenged states to generate solutions with the broader purpose of integrating evidence-based elements for turnaround initiatives into systemic improvement efforts for all schools.

Theme 1: Understand the Elements That Serve Challenged Students Well

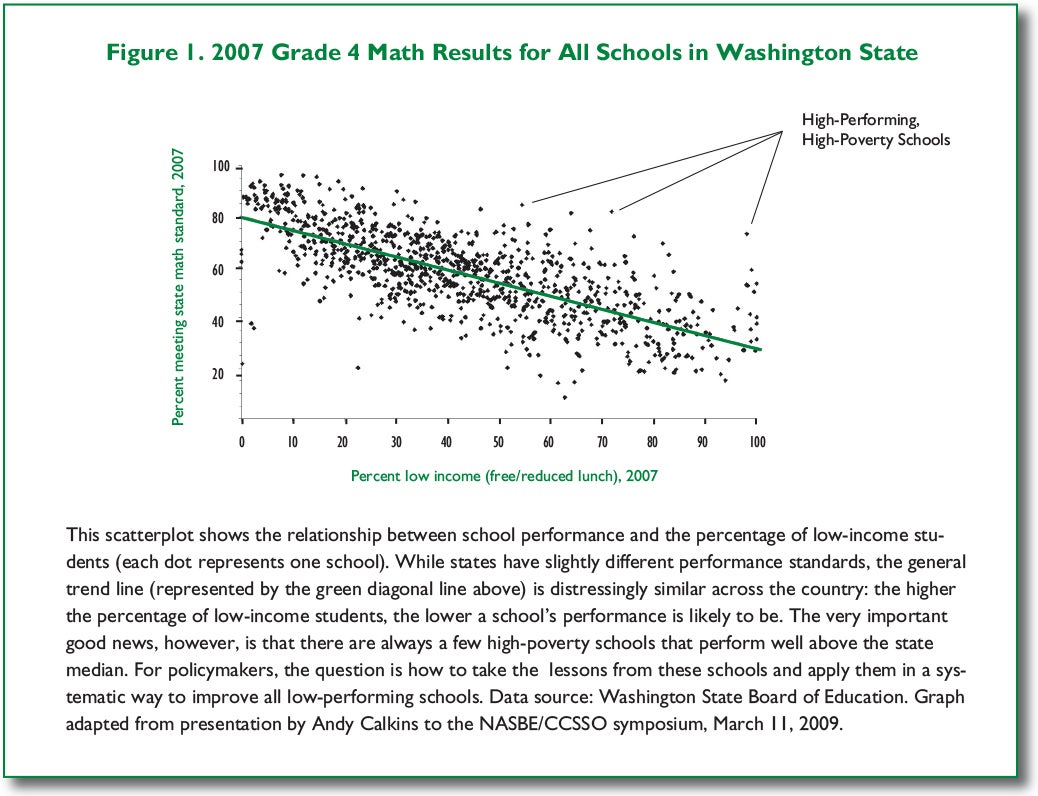

Calkins noted that consistent patterns of performance can be seen in all states that show a strong correlation between poverty and chronic under-performance, with the most severe performance defi cits seen in schools with over 50 percent poverty. He shared data scatterplots from a number of states that depict the negative relationship between poverty and achievement: as the number of students in poverty increases even by a small degree within schools, achievement declines (see example in fig. 1 on page 3). Yet, the data reveals that while dramatic variability is observed in high-poverty schools (those with over 50 percent poverty) and that the majority perform at dire levels, a small number of schools “beat the odds,” performing above the state median and proving that poverty and race are not destiny for low academic attainment.

Calkins said that the good news is that all states have a handful of these high-performing, high-poverty (HPHP) schools that can serve as a “new-world” model of schooling and as an opportunity to understand and replicate the hallmarks of what contributes to their success. Based on an extensive review of research from a number of fi elds, Calkins and his fellow researchers attributed the high-level performance to a major shift in organizational mission that moved these schools from the traditional conveyor belt, teaching-driven model (what’s taught) to a student-centered, learning-driven model (what’s learned). “Schools do not achieve high performance by doing one or two things differently—they must do a number of things differently, and all at the same time, to begin to achieve the critical mass that will make a difference in student outcomes,” Calkins said. “In other words, high-poverty schools that achieve gains in student performance engage in systemic change.” [6]

So how do we understand what those schools actually do that sets them apart? Th e attributes of HPHP schools have been incorporated into Mass Insight’s “Readiness” Model. Th is framework delineates a set of conditions, capacities, and attributes essential to organizing schools around a deep commitment to meeting the individual needs of every learner. HPHP schools diff er appreciably from others in their willingness to take on the concerns and challenges facing highly challenged, high-poverty students. What’s striking about these schools is their overriding mission to serve students and make decisions in their best interest, as opposed to responding to structures, contracts, and schedules that pose barriers to responding to the needs of individual learners.

Key Characteristics of High-Performing, High-Poverty Schools

Readiness to Learn

- Safety, Discipline, and Engagement: Students feel secure and inspired to learn

- Action Against Adversity: Schools directly address their students’ poverty-driven deficits

- Close Student-Adult Relationships: Students have positive and enduring mentor/teacher

relationships

Readiness to Teach

- Shared Responsibility for Achievement: Staff feels deep accountability and a missionary

zeal for student achievement - Personalization of Instruction: Individualized teaching based on diagnostic assessment

and adjustable time on task - Professional Teaching Culture: Continuous improvement through collaboration and jobembedded

learning

Readiness to Act

- Resource Authority: School leaders can make mission-driven decisions regarding people,

time, money, and program - Resource Ingenuity: Leaders are adept at securing additional resources and leveraging

partner relationships - Agility in the Face of Turbulence: Leaders, teachers, and systems are flexible and

inventive in responding to constant unrest

Source: The Turnaround Challenge: Why America’s Best Opportunity to Dramatically Improve Student Achievement Lies in Our Worst-performing Schools, Mass Insight Education and Research Institute, available online at www.massinsight.org/resourcefiles/TheTurnaroundChallenge_2007.pdf.

The model includes nine elements identified as attributes of HPHP schools (see textbox above).

The question for state boards and chiefs, of course, is how can states replicate the model HPHPs and create programs for underperforming schools in the context of a broader state system of supports and interventions? What’s often missed is that, although many of the barriers and conditions that impede major improvements also operate in higher-income communities, the limitations of the system and their impact on more affluent student groups are obscured. As the bar has risen for all students to achieve at higher levels of college and career readiness, states will need to consider how to scale the HPHP practices highlighted in the Mass Insight Readiness Model: their ability to cultivate shared responsibility for achievement among individuals throughout the system, the use of frequent assessment to personalize instruction, and the focus on the cultivation of a professional, collaborative teaching culture.

Theme 2 Questions for State Leaders

- How can changing organizational structures within the state help districts and schools address the

challenge of chronically low-performing schools? - What organizational issues need to be addressed? What would be the best possible state structure

for leading a turnaround effort (e.g., turnaround zone, new SEA division, P-16 subcommittee, quasiindependent

state authority, other)? Who would it include and how would it be funded? - Does your state recognize that turnaround success depends primarily on an effective people strategy that

recruits, develops, and retains strong leadership teams and teachers? - Does your state provide sufficient incentives in pay and working conditions to attract the best possible

staff and encourage them to do their best work? - Does your state’s turnaround strategy provide school-level leaders with sufficient streamlined authority

over staff, schedule, budget, and programming to implement the turnaround plan?

Washington State’s Guiding Principles for the Design of Turnaround Strategy

In 2006, the Washington State legislature charged the Washington State Board of Education with developing a statewide accountability system that identifies “schools and districts which are successful, in need of assistance, and those where students persistently fail [and where]…improvement measures and appropriate strategies are needed.” The legislature also asked the state board to develop a statewide strategy to help the challenged schools improve. Washington contracted with Boston-based Mass Insight Education and Research Institute and Seattle-based Education First Consulting to assist the state board in developing the plan for state and local partnerships to help Washington’s lowest performing schools improve.

This team convened a broad range of stakeholders in Washington to deliberate on what can be done for the schools in highest need, called Priority Schools. The goal was to prepare recommendations and proposals for the 2009 legislative session, as well as for the state’s Joint Basic Education Funding Task Force. While the recommendations specifically focus on strategies to help the most challenged schools, they link with the state’s larger accountability system and assistance plans for all schools.

The proposed plan frames a new kind of state and local partnership in standards-based reform for Washington State. It grew directly out of a set of “guiding principles” developed by the project’s design team, which was composed of more than 20 key stakeholder leaders. Based on an examination of the research on barriers to school improvement (both in-state and nationally), as well as on extensive conversations with various stakeholders, the state board and the design team developed general consensus around a set of guiding principles for turnaround in Washington State:

The Seven Guiding Principles

- The initiative is driven by one mission: student success. Whatever the reason, most students

are not succeeding in Priority Schools. This initiative is our chance to show that they can—and how they

can—so other schools can follow. - The solution we develop is collective. Every stakeholder may not agree with every strategy; aspects

of the solution may call for new thinking and new roles for all participants. But this challenge requires

proactive involvement from all of us. - There is reciprocal accountability among all stakeholders. This challenge needs a comprehensive

solution that distributes accountability across the key stakeholders: the state, districts, professional

associations, schools, and community leaders. - To have meaning, reciprocal accountability is backed by reciprocal consequences. Everyone

lives up to their end of the agreement, or consequences ensue. - The solution directly addresses the barriers to reform. As identified by Washington State

stakeholders, these include inadequate resources; inflexible operating conditions; insufficient capacity;

and not enough time. - The solution requires a sustained commitment. That includes sufficient time for planning, two

years to demonstrate significant improvement (i.e., leaving the Priority Schools list), and two more years

to show sustained growth. - The solution requires absolute clarity on roles—for the state and all of its branches, districts,

schools, and partners.

Source: Serving Every Child Well: Washington State’s Commitment to Help Challenged Schools Succeed. Final Report to the Washington State Board of Education (Boston, MA: Mass Insight Education and Research Institute, December 2008). Available online at www.sbe.wa.gov/documents/MassInsightFinalReport12-08.pdf.

Theme 3: Creating a “Turnaround Zone”

Calkins spoke of the need to change the systemic conditions that actively shape how everyone behaves in schools. He noted there is evidence that leaders of HPHP schools succeed largely by circumventing the most dysfunctional obstacles presented by the system. In order to foster this kind of behavior in more low-performing schools, Calkins recommended clustering schools (organized around a common attribute such as school type, reform approach, or feeder pattern) into Turnaround Zones. Within such zones, school leaders are given increased autonomy and flexibility over such areas as:

- Staffing—including more authority over hiring, placement, compensation, and work rules;

- Scheduling—including longer school days, longer year, or year-round school calendar;

- Funding—including both more resources and more budgeting flexibility;

- School program—including more authority to design the program to specifically fi t the needs of the school’s students, both academically and psycho-socially; and

- Leadership—within this framework, districts need to establish professional norms for strategic human capital initiatives that focus on developing the capacity of school leadership teams to lead school turnaround. In addition to designing systems for attracting and retaining quality teachers and leaders, capacity-building hinges on creating networks and partnerships with entities that can provide turnaround expertise.

A number a big-city districts, including Chicago, New Orleans, New York City, and Philadelphia, have been experimenting with Turnaround Zones for several years. Th e idea is to enable local leaders to earn the opportunity to turn around schools in partnership with the state and through what Calkins called “the three C’s”: changing conditions, capacity, and clustering.

The core strategies include crafting a carrot and stick approach, creating differentiated levels of intervention in districts based on the degree of need, and balancing flexibility and autonomy for districts to leverage their willingness to change prior to losing control to the state under the final NCLB designation—reconstitution.

Districts can opt into a partnership with the state and receive resources and other supports in exchange for meeting specificcriteria and benchmarks. It is essential to provide countervailing incentives to generate bold action that differs from the standard approaches taken by states to intervene in low-performing schools. Strong interventions are rare because they tend to confront established interests and state and district constraints. In other words, the state must carefully balance the degree of autonomy over operating conditions (time, people, money, and resources) with the accountability for making progress within an agreed upon timeframe. The goal is to reduce the compliance burden and redirect how decisions are made in accord with student interests and the mission of the school. The state reserves the final option to change governance and intervene if insufficient progress is made, but the intent is to give districts the incentive to opt into a self-designed turnaround strategy before restructuring or reconstitution is needed.

Theme 3 Questions for State Leaders

- Within the protected Turnaround Zones, does your state collaborate with districts to organize turnaround

work into school clusters (by need, school type, region)? - How can schools be clustered so reforms can expand systemically, not just taking place in one school at a time?

- Does your state have a strategy to develop lead partner organizations with specific expertise needed to

provide intensive school turnaround support? - What’s needed to leverage innovation and improvements at the district level to serve, high-poverty students?

- What models already exist in the state that turnaround efforts can build on? These could include charter, pilot, alternative, or other schools that set aside some normal operating structures in order to give leaders more freedom to allocate people, time, money, and programs according to their students’ needs.