About 10 years ago, staff at Fleisher Art Memorial recognized that the organization was not keeping pace with demographic changes in its Southeast Philadelphia neighborhood. Although Fleisher had off-site community and school programs that served the neighborhood’s growing number of residents of Latin American and Southeast Asian descent, this population was not well represented among the approximately 4,000 students taking on-site classes. In 2008, Fleisher received a Wallace Excellence Award to identify barriers to their attendance and launch programs to eliminate them. The school then saw a subsequent increase in the perception of Fleisher as an inclusive organization and experienced an uptick in enrollment of area youth in its classes. That effort is described in a 2015 case study.

Because audience diversification can take many years to accomplish, we were eager to revisit Fleisher and see how things now stand. We found an organization that is not only attracting an increasingly diverse audience but is also asking more questions about itself and inviting its community to help provide answers.

Engaging the Community

Fleisher Art Memorial was founded in 1898 in Southeast Philadelphia, which has been an entry point for newly arrived immigrants throughout its history. For most of the 20th century, Fleisher students came from a patchwork of nearby communities of European heritage. In recent decades, however, those populations have been replaced by newcomers from Latin America (mostly Mexico) and Southeast Asia, groups that Fleisher staff came to realize were not signing up for classes.

Though many of newly arrived immigrants had practiced art in their home countries—and it continued to be an important part of their lives—they did not know that Fleisher could provide them with art-making opportunities. Fleisher’s research revealed that even though the institution was committed to making art accessible to everyone, regardless of economic means, many of the new immigrants believed the school was for wealthier people of European descent, and in the absence of other information, they assumed they would not be welcome. Therefore, the staff put aside their original aim to engage community residents by offering new programs and instead focused on the need to challenge an inaccurate perception.

With that in mind, the school launched a community engagement initiative that integrated Fleisher activities into neighborhood daily life. New programs included:

- ColorWheels, a van serving as a mobile art studio that allowed the school to bring art-making to dozens of neighborhood parks, festivals and schools;

- “FAMbassadors,” two local residents who joined the staff to raise awareness of Fleisher and notify the institution of areas where its programs could complement and enrich celebrations and other happenings; and

- Expansion of ARTspiration, its annual day-long street festival, to make it more inclusive of various community groups.

At the same time, staff members underwent cultural competency training to create a more welcoming environment on-site. They also participated in workshops on topics such as: building relationships, collaborations and partnerships; marketing and messaging in the community; and developing strategies to work with local agencies. After the staff did this groundwork, the neighborhood’s impression of Fleisher as elitist softened considerably, with visitor surveys showing a sharp increase in the perception of Fleisher as committed to serving non-English speakers and people born outside the United States. Moreover, the school began to serve more students from the neighborhoods immediately surrounding it.

Continuing Existing Programs and Creating New Ones

Since the 2015 case study, Fleisher has continued, and in some cases expanded, its engagement programs in these ways:

- The ColorWheels van still brings art-making throughout the neighborhood, with funding in part from the PNC Foundation.

- ARTspiration has grown and become more of a family festival. Last year, more than 7,000 people visited, a far cry from the less than 2,000 who came just five years ago. The organization still invites vendors and performers who reflect the community’s diversity. According to former director of programs Magda Martinez, ARTspiration has been one of the most effective ways of introducing large numbers of people to Fleisher.

- As part of their orientation, new staff and board members learn about the community research and engagement work to help them understand its objectives and how they link to Fleisher’s mission.

- Fleisher has hired its first communications director, translated promotional and registration materials into multiple languages and hired bilingual staff and faculty.

- A new video-rich website, Fleisher.community (http://fleisher.community/), highlights Fleisher’s activities throughout the neighborhood.

- With the departure of one of the original FAMbassadors and the organization’s changing relationship with the communities, staff members are rethinking what role these liaisons will play in the future.

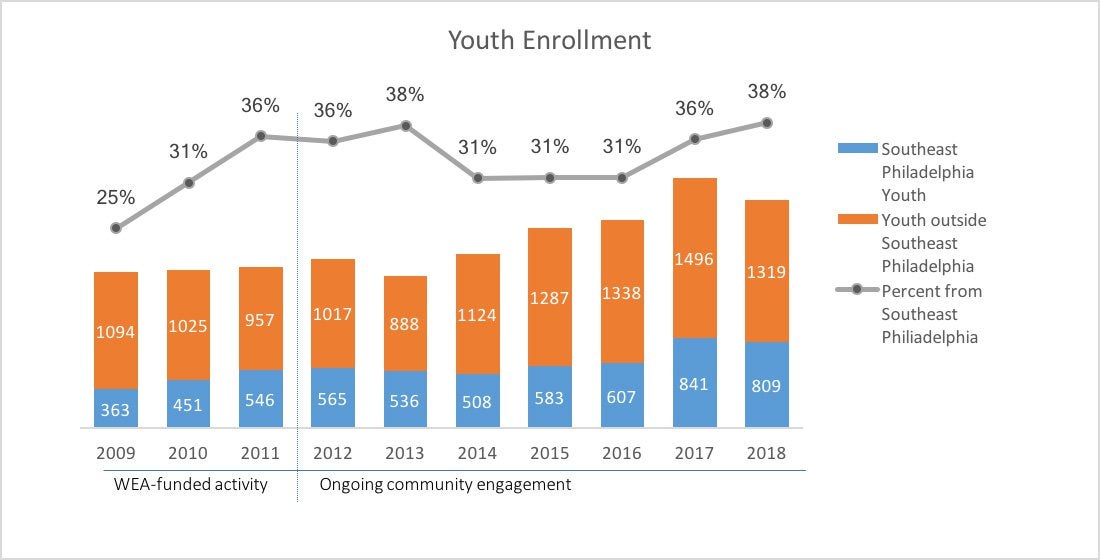

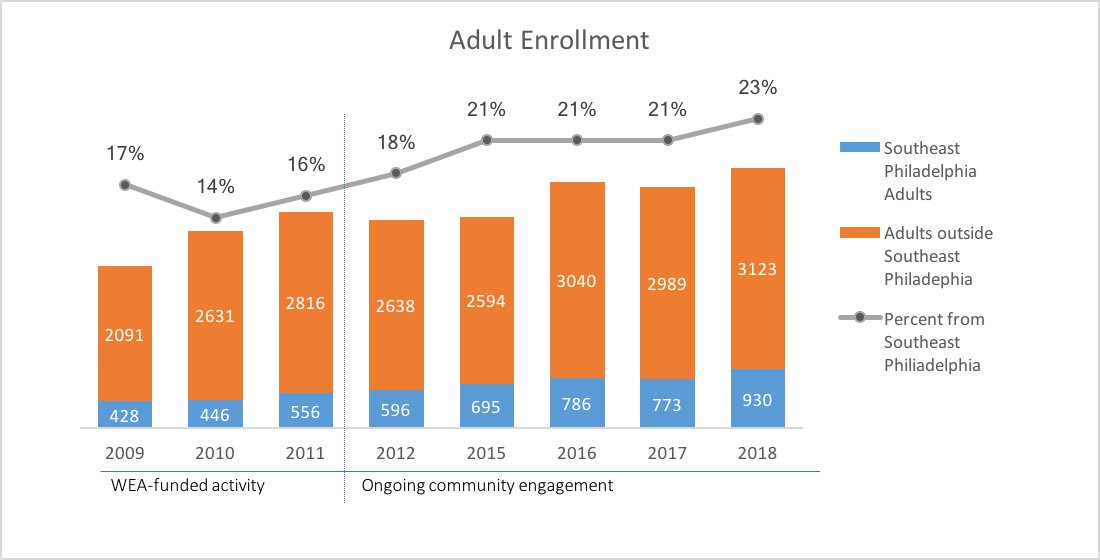

The following charts show youth- and adult-program enrollments and the percentage of those enrollments that draw from Southeast Philadelphia (defined as zip codes 19147 and 19148). The greatest growth has been in youth programs, with young people from the neighborhood now making up 38 percent of total enrollment, confirming research findings that suggested that residents wanted art for their children. While growth in adult programs has been slower, neighborhood residents now make up a larger percentage of such enrollment than in the past.

Youth Class and Workshop Enrollment

Adult Class and Workshop Enrollment (incomplete data from 2013 and 2014 not shown)

One new program forging relationships with neighborhood residents is the celebration of the Mexican holiday Día de los Muertos at Fleisher. Over several weeks each fall, a working artist and community members gather to create the art used for the festivities at Fleisher, including a large thematic altar (an “ofrenda”) that honors those who have passed away. There are also workshops to make papier-mâché sculptures and paper marigolds. The celebration culminates with face painting and a parade in the streets surrounding Fleisher (with music from community artists) and a gathering at the school.

The Día de los Muertos celebration began six years ago when Fleisher FAMbassador Carlos Pascual Sanchez connected Exhibitions Manager José Ortiz-Pagán with a local merchant hosting an ofrenda. The merchant, in turn, connected Ortiz-Pagán to local artists, dancers and community leaders involved with other Día de los Muertos festivities around the city. They formed a volunteer committee to create a large-scale ofrendaat Fleisher, inviting the local Mexican community and others. Ortiz-Pagán notes that the school did not invite an artist to come in for just one weekend and build an ofrenda. Instead, it asked the community to inform every step of the process, start to finish, in order to better nurture a long-term relationship.

Run by an autonomous committee of eight community members who create the budget and plans, the festivities have grown to become one of the largestDía de los Muertos celebrations in the Northeast. Fleisher provides space, materials and expertise such as fundraising and grant-writing support. Last year the observance also included a community fundraiser. Staff members say it was welcomed by neighborhood residents, who wanted to play a larger role in supporting the effort, and by Fleisher’s board and donors, who appreciated the event as an opportunity to gain a deeper understanding about the cultural tradition of Día de los Muertos.

Ortiz-Pagán sees the commemoration as emblematic of Fleisher’s commitment to being an integral part of Southeast Philadelphia by supporting communities to manifest their cultures, a mission reflected in other art-based partnerships as well. Such partnerships include a new Bring Your Own Project initiative funded by the Pew Charitable Trusts, which invites artists to Fleisher to work with surrounding communities and the social service organizations that represent them. Says Martinez, “Instead of the artist coming in with a project already set, the artist spends time meeting the community, and we prepare participants to talk about what’s important to them and if they see art playing a role for their concerns in their community and if so, how?”

Working as Part of the Community

Stemming from the first period of research and program development, programs like Bring Your Own Project represent a rethinking of the institution’s approach to engaging with the community. In reaching out to the people they hope will be involved, staff members pose questions and try to learn about neighborhood needs before acting. They also constantly ask themselves why they want to take on a particular initiative and how it will have an impact on the community.

Martinez notes that the questions are the same regardless of whether the work involves community engagement or other Fleisher programming. In thinking through a new program for older adults, for example, Fleisher has reached out to a predominantly Latino immigrant–serving health agency to identify what art forms most interest its older clients, what kind of engagement would be best for them and what Fleisher can provide that would enrich their lives and is not available elsewhere. This inquiry has led to a new ceramics curriculum designed to promote story sharing and reduce social isolation among the elderly in immigrant communities.

This way of developing programs is a significant shift for the institution. “Questioning is now an intrinsic part of Fleisher’s culture. I’m not so sure we were good at that ten years ago,” says Martinez. “We now question ourselves, what we’re doing and why. We’re more aware of what’s happening in the city and on a national level.”