An unprecedented level of federal financial support is flowing to schools as dollars from the COVID relief package known as the American Rescue Plan Act get distributed, along with education funding from conventional sources, such as the Title I program. So, here’s an idea for school district and state education officials. How about using some portion of the federal money for a too-often-overlooked factor in improving schools: cultivating a corps of effective school principals?

That was one of the messages delivered by Patrick Rooney, director of school support and accountability programs for the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Elementary and Secondary Education, during a recent webinar. Rooney emphasized that Rescue Plan and other federal funding is available to support the development of effective principals, whose power to drive school improvement, he emphasized, has been confirmed by research.

“Principal pipelines and support for principals and leaders are certainly well within the realm of things you can spend your federal funds on,” Rooney said to an online audience of more than 400 education officials and others. “The research, again, is clear: that having a strong and capable leader has a huge impact on how kids are doing in classrooms and how teachers are operating.

“It's a clear link to improving the performance of the school. So it is a clear opportunity for those of you who want to think about how your American Rescue Plan funds—and, then, moving forward in your Title I and Title II funds—can all be tailored together to meet this particular need.”

The webinar, Paying for Principal Pipelines: Tapping Federal Funds to Support Principals and Raise Student Achievement, marked the launch of a guide to inform school district and state education officials about the numerous sources of federal funding—both longstanding and new—for boosting school leadership. You can find a few expert tips from the new guide at the end of this post.

One approach districts are taking using to develop leaders is to build what Wallace has come to refer to as “comprehensive, aligned" principal pipelines. These pipelines are “comprehensive” because they consist of key components (such as leader standards and strong on-the-job evaluation and support for principals) that together span the range of district talent management activities, and they are “aligned” because these policies and procedures reinforce one another. Jody Spiro, director of education leadership at Wallace, described the components and presented the results of a 2019 study of six districts that had put them into place: Students at the elementary, middle and high school levels outperformed students in comparison districts in math. Students at the elementary and middle school levels also outperformed their peers in reading. Moreover, these improvements kicked in only two years after the pipelines were built.

Education officials interested in building such pipelines for their districts or states might assume, in error, that they will have to do so absent federal help. “Oftentimes, what we see is that districts use the funds for the same program from one year to the next because they know that they won’t get audited if they spend their money in this way or ‘this is how we spent it, so this is how we will continue to spend it,’” Rooney said. “But that doesn’t need to be the case. And you, actually, at the local level have a tremendous amount of flexibility with how you use your federal funds.”

Rooney also stressed the role of principals in recovery from the pandemic. “We are in a critical moment in time after the past year and a half of COVID,” he told listeners, noting that earlier in the day, he had attended a different webinar and heard about the impact on school districts in one state of the learning loss students have experienced as a result of the health crisis. “It just hit home how important it is to have strong and capable leaders to meet this moment in time,” he said.

Paul Katnik, assistant commissioner at the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, talked about the benefits of—and funding for—that state’s effort to develop effective principals. The Missouri Leadership Development System, which covers the gamut of principal development from aspiring to veteran school leaders, provides education and support to more than 1,000 principals in urban and rural districts, charter schools included. The effort is paying off, Katnik said, in, among other things, lowering principal churn. The retention rate for system principals is 10 percent higher or more, depending on the region, than for other principals in the state. How is this work paid for? Through about $4 million a year in federal Title I, Title IIa, American Rescue Plan, grant, and state funds, according to Katnik. “If you’re going to create a state system that functions at a high level in all different types of school communities, it takes a significant investment,” he said.

Michael Thomas, superintendent of Colorado Springs School District 11, concurred with Katnik’s overall point about the value of funding for efforts to promote principal effectiveness. “There’s never been a successful turnaround story without a strong leader at the helm,” he said. “And coming into District 11, it was very clear to me that, if we were going to really improve the district over time, we needed to make sure that we were bringing significant investment into our leadership.” Thomas, who oversees a district of about 24,000 students and 55 schools an hour south of Denver, spoke of using federal money not only to aid teachers facing unprecedented demands during the pandemic, but also to support new and aspiring principals. School leaders on the job from one to three years receive executive coaching from an outside vendor, and the district is cultivating an “Aspire to Lead cohort” of potential principals ready to step in when vacancies occur. “We want to make sure we’re holding [our leaders] ‘able,’” he said. “That’s accountability with support.”

Beverly Hutton, senior advisor and consultant to the CEO at the National Association of Secondary School Principals, which represents more than 18,000 school leaders across the country, said she was heartened by state and district efforts to support principals. “The complexities of the job…have increased exponentially over the past decade,” she said. “And then the pandemic exacerbated that and highlighted those complexities in ways we had not imagined.” Hutton underscored the role of principal development work in promoting equity in education. “It is extremely important that ongoing training and investments need to focus on ensuring principals are equipped to address the systems and processes that need to change in order to honor the lived experiences of each student,” she said.

State and district leaders looking to follow the example of Missouri and Colorado Springs may need help figuring out where their principal pipeline work fits into today’s uncharted funding landscape. That’s where the new guide comes in. Prepared by EducationCounsel, a mission-based education consulting firm, and the research firm Policy Studies Associates, Strong Principals, Strong Pipelines: A Guide for Leveraging Federal Sources to Fund Principal Pipelines is designed to help districts ask good questions and test their assumptions about federal funding for principal pipelines.

Sean Worley, senior policy associate at EducationCounsel, walked webinar participants through the features of the guide. For each of seven key components of a strong principal pipeline, the guide specifies relevant activities and the federal funding sources that may be the best match for each. Funding information for activities in all seven categories is also compiled into a single “at-a-glance” table. Part 2 of the guide provides details about each relevant funding stream, including its purpose and allowable uses; how it is allocated (e.g., by formula or in the form of competitive or discretionary grants); and the primary recipients.

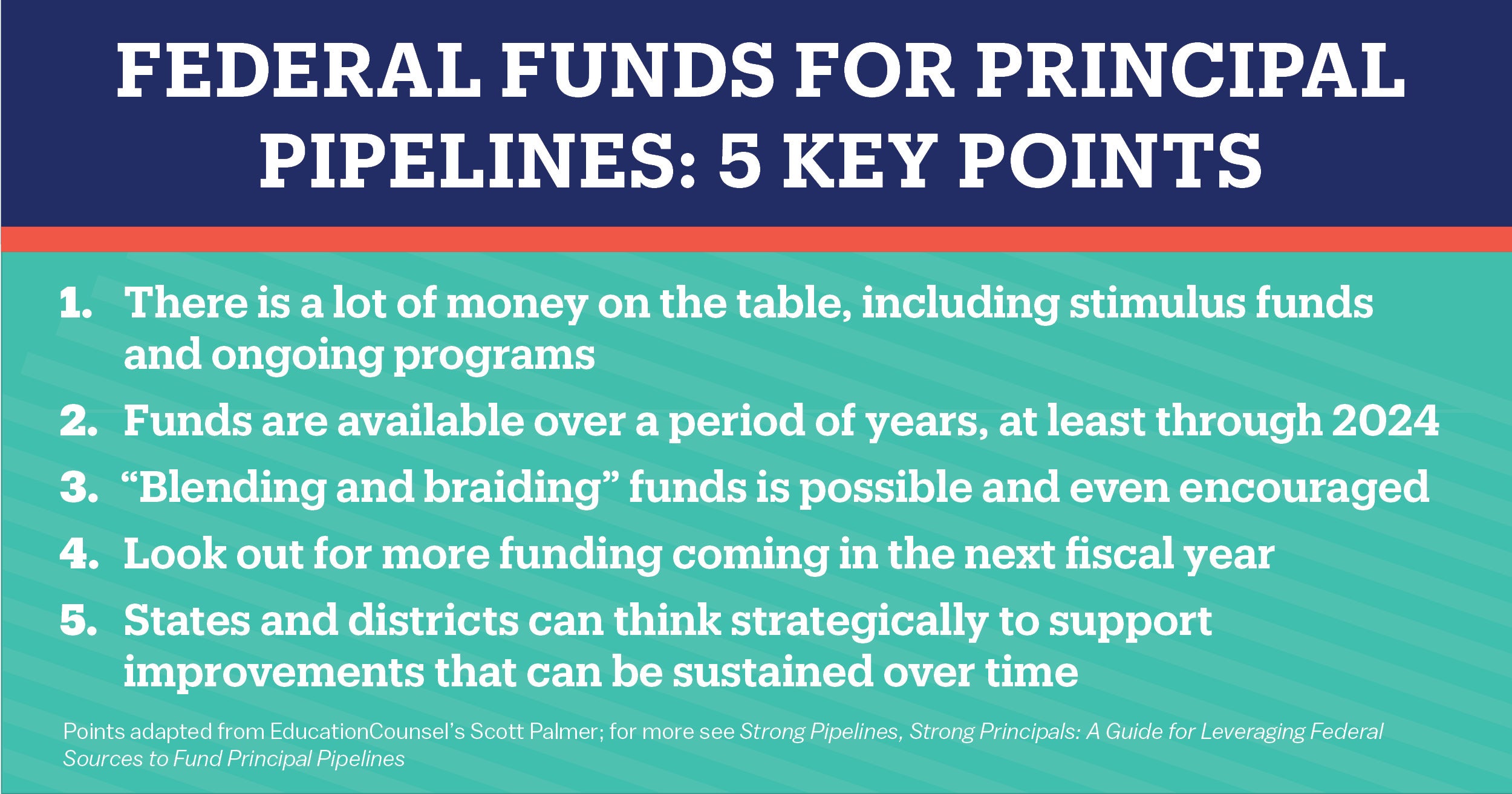

Worley’s colleague Scott Palmer, EducationCounsel’s managing partner and co-founder, left state and district leaders with five “big points” to chew on:

- “There’s a lot of money on the table that can support principal leadership and principal pipelines,” he said. “I say that notwithstanding the unbelievable challenges we have and the needs that are existing right now.” The sources include stimulus funds and ongoing federal program funds.

- “These funds are available over a period of years.” Palmer pointed out that American Rescue Plan Act funds are available at least through the 2024 school year. Districts and states are allowed to review and improve their initial plans to ensure funding is having the intended effect.

- “Blending and braiding” funds is possible, and even encouraged. “If you find yourself in a place where dollars are siloed, staff are siloed,” Palmer said, “please try to…pull those funding streams together.”

- “There may well be more funding coming.” Palmer noted that Congressional appropriations for the next fiscal year are likely to include significant increases in allocations to core programs like Title I, and the Build Back Better Act includes direct investments in principal development activities. “We may have to come out with a new version [of the guide] with yet another column [in the table],” he quipped. “So, stay tuned.”

- Palmer’s fifth point regarded thinking beyond the immediate crisis. He urged state and district officials to work strategically and consider how federal funding could support improvements that can be sustained over time. Palmer acknowledged that this isn’t easy because education officials are focused on meeting urgent needs and want to avoid falling off a “funding cliff” when federal support ends. Still, he said, he is seeing places that are taking a longer-term approach—one that can “not just really fill those important holes but do it in a way that plants seeds for future change.”