In many urban school districts, principal supervisors have a daunting task. Overseeing an average of 24 principals, they are also accountable for numerous administrative and other responsibilities, from monitoring supplies to ensuring government forms get completed on time. This makes concentrating on school leaders and their needs close to impossible. Wallace’s Principal Supervisor Initiative is seeking to see if that picture can be changed. It is funding a four-year effort in six districts that are working to reshape the supervisor job so it can focus on supporting principals to be as effective as they can be, especially in guiding schools to high-quality instruction.

Recently, Wallace published A New Role Emerges for Principal Supervisors, the first report in a study looking at the effort, and it showed some promising findings, concluding that over the first three years of the initiative the six districts were able to make substantial progress in giving the supervisor job a makeover.

Recently, Wallace published A New Role Emerges for Principal Supervisors, the first report in a study looking at the effort, and it showed some promising findings, concluding that over the first three years of the initiative the six districts were able to make substantial progress in giving the supervisor job a makeover.

We caught up with the researcher leading the study, Ellen Goldring, the Patricia and Rodes Hart Professor and Chair in the department of leadership, policy and organizations at Vanderbilt’s Peabody College, to see if she could tell us more.

What was the problem that districts in this initiative were seeking to address?

School districts continually strive to support and develop their principals and improve their effectiveness. Most often, this occurs through professional development. But, most urban districts have a central office structure that includes principal supervisors. Typically, supervisors focus on administration and bureaucratic compliance. The initiative has a straightforward question: Can districts transform the role of principal supervisors from compliance officers to coaches and developers of principals? What does it take to make this change? And, does this change help develop effective principals? This report addresses the first two questions.

Do we have a sense—understanding it's early—about the benefits and challenges of the changes the districts were tackling?

We have learned a great deal about the changes districts have made to support the new role, and what the new role entails.

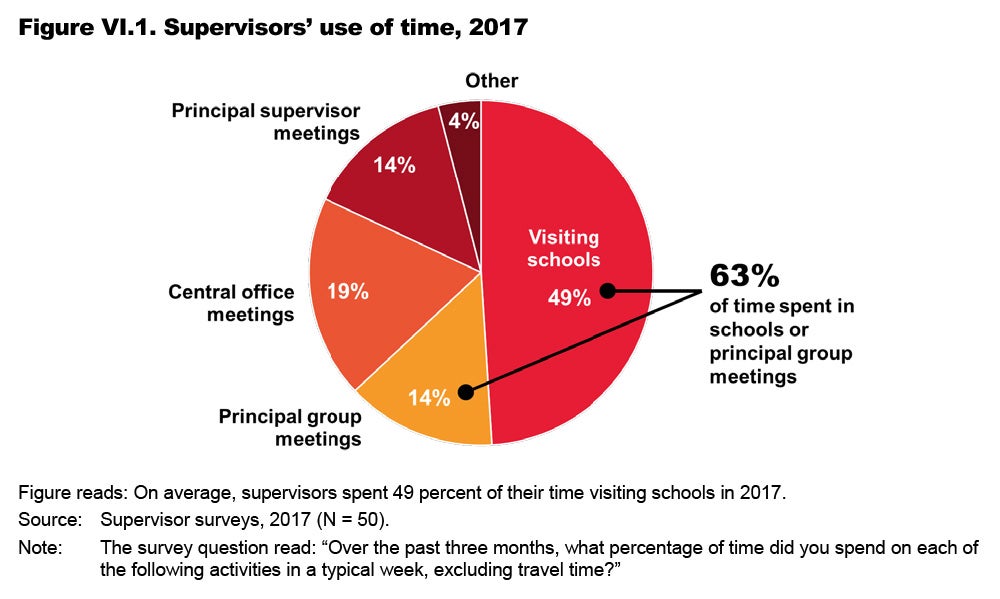

The daily work of supervisors has changed. The clear benefits include supervisors spending time in schools and working with networks of principals on instructional leadership. Supervisors engage in walkthroughs, coaching and providing more ongoing feedback to principals; they have a deep sense of the context of each principal’s school and develop closer relationships. Supervisors are able to evaluate principals based on their ongoing, firsthand knowledge and understanding of each principal. Principals report productive relations with their supervisors.

The change in the role occurred as a result of revising job descriptions and reducing the span of control—the number of principals each supervisor works with—to about 12, on average. For the first time supervisors received dedicated, unique training to develop the skills needed to be effective in their roles. This training often involved shared visits to schools where supervisors observed each other coaching and providing feedback to principals. Supervisors worked together to develop a shared set of practices and common approaches.

To support this new role, other central office roles and responsibilities needed to shift, and some departments were reorganized. Work previously handled by supervisors needed to be reallocated; as a result communication patterns had to change. Investing other central office departments in the change is a challenge and an ongoing process.

Other challenges include continuing to clarify the new role and to balance expectations; deepening and further developing consistent and effective practices for supervisors; and differentiating supports for principals. There are resource implications as well.

What are districts learning about making decisions on what supervisors to assign to what schools?

First, they learned that this is a really important decision. Most districts consider a combination of school level, geography and feeder patterns. Others take into account performance levels, principal experience and school themes. The decision helps the districts think strategically about principal networks and learning communities as tools for support, sharing and development. The decision also helps districts think through matching supervisors’ skills, experiences and expertise to schools strategically. Districts learned that they also need to think about not only the average span of control, but balancing the span of control for each supervisor with the unique needs of each school.

How are the districts understanding the concept of "instructional leadership"—and what role do principal supervisors play in supporting it?

Districts understand instructional leadership entails a deep understanding of the conception or framework of high-quality and rigorous instruction used in the district, and then what principals do to support and propel teachers in their instructional quality. Instructional leadership also entails developing the school culture and community for academic and social learning.

The link between the district’s instructional quality framework and instructional leadership is central. Some districts are further along in articulating this link than others. Principal supervisors work with principals on instructional leadership by coaching them through analyzing data, providing feedback to teachers, observing classrooms together, and creating principal learning communities, to name a few of their core activities.

What should districts contemplating revising this role think about?

They should know that changing the role of the principal supervisor is a district-wide effort with multiple components, and requires communication and coordination throughout the district; it is not “simply” a role redesign. In fact, all the districts realized early on that making changes to the work of the central office would be necessary to facilitate the change to the supervisor role.

As in every large-scale change effort, the leadership of the district should be clear about how this change contributes to the overall strategic goals of the district. Buy-in from core constituencies is key, especially because there are resource implications in terms of reducing the span of control, and the whole district will be involved.

Lastly, I would say that simply reducing the span of control will not lead to role change. Paramount are a clear vision and expectations for the role, a delineation of instructional leadership expectations for principals and a strategy for supervisor training and support.

What surprised you in your research to date?

I was surprised by the depth of understanding and excitement about the need to change the principal supervisor role.

I think this is a very powerful example of district reform that rallied around a specific focus: changing the principal supervisor’s role. It is a very hopeful story—one that suggests when change initiatives have clarity, alignment and focus, districts make important changes.

I was surprised about the extent to which the role before the initiative really was a catch-all for everything and anything schools needed, and it was very idiosyncratic within the same district. We saw how important it is to develop shared understanding and specific skills of supervision, such as implementing specific coaching models, or using protocols for walkthroughs. Developing a collaborative, professional culture amongst supervisors helped them in turn work with principals in professional learning communities.