Summary

In some school districts, performance evaluations of principals are a yearly exercise in compliance, described by one principal as amounting to roughly the following: “You do a great job. Sign this.” What’s missing are ideas about how the principal might improve his or her efforts.

The six school districts in a Wallace Foundation effort to develop a larger corps of effective principals are seeking to change that picture, according to this article in the May 2017 issue of ASCD’s Educational Leadership magazine. Their aim is to use principal evaluation and the procedures for carrying it out to help improve principal performance. Revamped assessments on which the principals are rated are now tied closely to the districts’ standards for principals. Moreover, the evaluations are carried out by supervisors who work closely with the principals throughout the school year, helping them recognize their strengths and offering guidance to overcome weaknesses. The result, as one principal told researchers, is that he no longer thinks of performance reviews as “this big evaluation,” but as “an ongoing conversation” about his goals and his progress toward them.

The article examines in depth how this new approach is playing out in one of the Wallace-supported districts, Hillsborough County, Fla., which encompasses the Tampa area. There, says an assistant superintendent, evaluation has been changed from “something we did at the end of the year” to a “growth tool” for principals.

During her five years as an assistant principal at a Tampa, Florida, elementary school, Delia Gadson-Yarbrough grew accustomed to an annual performance evaluation ritual that amounted roughly to the following: “You do a great job. Sign this.”

Hardly useful.

Today, as principal of another Tampa school, Anderson Elementary, Gadson-Yarbrough’s experience couldn’t be more different. Over the summer, she sits down with her supervisor and goes over the ratings she has been given, receiving a detailed assessment of her work in key facets of her job, including improving instruction, managing people, and building school culture. Nor is her review a one-shot deal. It’s the culmination of ongoing feedback she has received over the course of the year from her supervisor. Equally important, the evaluation system is focused not on rating school leaders to determine who should be put on notice or let go, but instead on giving principals, especially those in their initial years on the job, guidance to help them grow and become better in their jobs.

Gadson-Yarbrough, who has been a principal for a little over three years, welcomes the approach. “I’ve used that information and feedback to grow as a leader and set goals for myself for the next school year,” she says. “This is looking at you from all sides. It’s just way more meaningful.”

Eighty-five percent of the respondents said they considered the evaluations worthwhile. This stands in striking contrast to earlier research.

The shift in Gadson-Yarbrough’s evaluation experience came about not because she moved from assistant principal to principal, but because of a major change in how her employer, the Hillsborough County Public Schools, handles the evaluation of all its school leaders. The district’s aim is to use the evaluation process more intentionally to shape more effective leadership for each of the district’s 270 or so schools and the approximately 212,000 diverse students they serve.

“Evaluation had just felt like something we did at the end of the year,” says Tricia McManus, the school system’s assistant superintendent of educational leadership and professional development. “We’ve tried to change that approach so it’s growth tool that really describes the principal’s work here in Hillsborough County. It helps with the definition of the role and the connection to goal-setting and professional learning.”

Improving the Principal Pipeline

McManus is not alone in thinking that improving evaluation systems can help bolster school leadership. She has like-minded peers in six large school districts taking part in the Principal Pipeline Initiative, an effort funded by The Wallace Foundation (for which I work) to develop a stable corps of effective school leaders—and to disseminate lessons from this work. The six districts have been working since 2011 to improve the way principals are trained, hired, supported, and, yes, evaluated. In addition to Hillsborough, the districts are Denver, Colorado; Charlotte-Mecklenburg, North Carolina; Gwinnett County, Georgia; New York City; and Prince George’s County, Maryland.

In making evaluation a tool for principal growth, the districts have begun to see some positive responses. An independent research study commissioned by The Wallace Foundation included a survey of novice principals (those on the job for three years or fewer) across the districts. The study found “consistently positive reviews” for the revamped evaluations (Anderson & Turnbull, 2016, p. 34). For example, 85 percent of the respondents said they considered the evaluations worthwhile. This stands in striking contrast to earlier research, unconnected to the Pipeline project, finding that principals were generally skeptical of the usefulness of their performance evaluations (Portin, Feldman, & Knapp, 2006).

In addition, 88 percent of the novice principals in the Pipeline districts saw their evaluations as fair—63 percent to a “great” or “considerable” extent. Finally, at least 75 percent of the novice principals agreed that the Eighty-five percent of the respondents said they considered the evaluations worthwhile. This stands in striking contrast to earlier research. evaluations accurately reflected both their performance and the breadth and complexity of their jobs, another notable contrast from past research findings on principal evaluations. (A forthcoming study from the RAND Corporation will examine the impact of the Principal Pipeline Initiative on student achievement and other outcomes.)

Creating an Aligned System

One of the districts’ frst undertakings after joining the Pipeline effort was to scrutinize—and modify as necessary—the standards they had in place for school principals. Those standards then became the guide for how principals would be trained, hired, and evaluated. Drawing up a new approach to assessing a principal’s performance became, in part, an exercise in matching the evaluations to the new principal standards. To ensure that the two were in sync, Hillsborough established an alignment committee made of up of the same people (principals, district staff members, and others) who had helped draw up the standards (Turnbull et al., 2016).

Another major consideration shaped the development of the new evaluations as well: meeting state evaluation requirements. For all six districts, this meant the evaluations would have to incorporate two central indicators—how the principals carried out their jobs (professional practice) and how their school’s students were performing (student growth), in most cases with specific weights given to each. Student growth accounted for 40–70 percent of a principal’s rating, depending on the state. Within these categories, however, the districts had a fair amount of leeway. For student growth, for example, a number of them took into account not only student results on state tests but also factors like attendance and the extent to which students met school-level learning objectives. Hillsborough, which began phasing in the new evaluation system in the 2011–2012 school year, eventually factored in data on improvements among the lowest-performing students (Anderson & Turnbull, 2016).

Today, the result of this work for Hillsborough County is an evaluation that, in addition to student growth, examines principals in the five areas emphasized by the district’s standards: achievement focus and results orientation; instructional expertise; managing and developing people; culture and relationship building; and problem solving and strategic change management.

The district’s principal supervisors, known as area superintendents, are tasked with basing their assessments of principals on concrete evidence, and the district has developed a rubric that lists a number of elements that the evaluators should examine in each of the five standards-based areas. The rubric notes, for example, that a principal exhibits instructional expertise through three elements: conducting high-quality classroom observations; using data effectively (and ensuring that teachers do, too) to bolster student’s learning; and ensuring that the curriculum, instructional strategies, and assessments align with one another.

The rubric also offers examples of evidence that the evaluator should gather. To help determine a principal’s skill in carrying out classroom observations, for example, the evaluator is expected to examine a range of data that includes surveys of teachers. Finally, the rubric offers the evaluators guidance on how to decide which of four possible ratings—requires action, progressing, accomplished, and exemplary—a principal merits in each area. In classroom observation, for instance, the difference between an accomplished and an exemplary principal would be, among other things, the difference between a principal whose “schedule shows regular and ongoing observations and walkthroughs” and one who “scores at the highest levels on all data elements related to feedback.”

The ratings are calculated into a final score for the principal’s written evaluation, which helps determine performance pay for principals. A breakdown of the competency scores, meanwhile, is used to map out individualized professional development plans for the school leaders.

Hillsborough isn’t unique among the Pipeline school systems in using evaluations to provide targeted support. According to the survey study, across the six districts, a large majority of the respondents who were told they needed to improve in at least one practice area reported receiving help in that area. For example, 86 percent of those who had faltered in instructional leadership said they subsequently received assistance to bring them up to speed in this competency (Anderson & Turnbull, 2016).

A New Approach to Principal Supervision

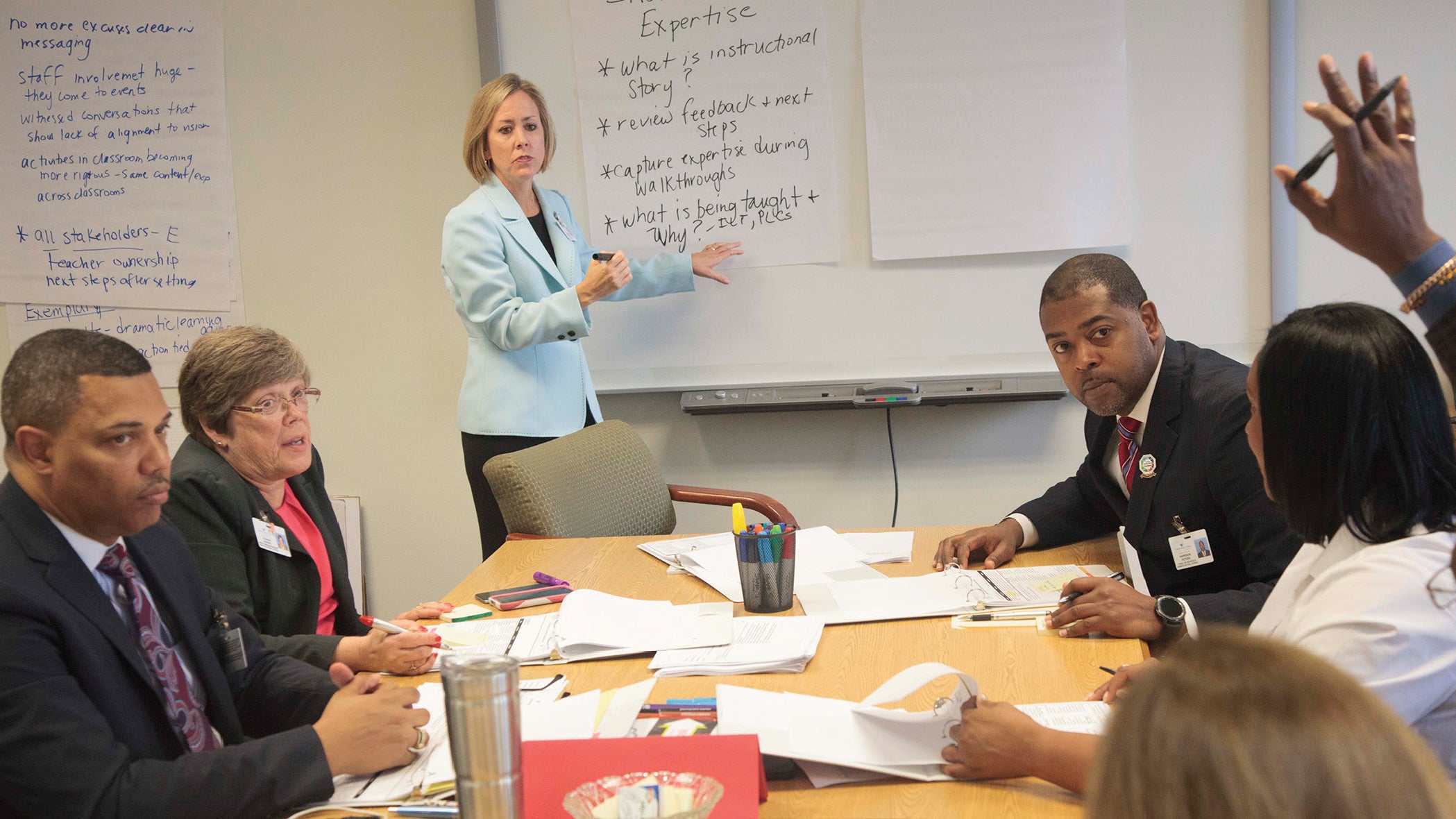

The change in the evaluations has gone hand-in-hand with a change in the principal supervisor’s role. Many supervisors in Pipeline districts are now providing more direct support to principals. “They are in schools more than ever before, integrating the rubric in their everyday work with the principals,” McManus says of Hillsborough’s eight area superintendents. They “are much more intentional about their work, collecting a lot more evidence and doing a lot of coaching with the principals.” Principals have taken notice. For example, 77 percent of the survey respondents said their supervisors had helped them “create or improve structures and strategies that support my teachers in using student data to drive instruction” (Anderson & Turnbull, 2016, p. 43).

For her part, Gadson-Yarbrough talks to and gets guidance from her area superintendent at least twice a month. Sometimes the supervisor drops in on faculty or school committee meetings. She and Gadson-Yarbrough also catch up at the monthly small-group professional development sessions that area superintendents hold with their principals. In addition, there are formal school visits, such as one last December when the supervisor brought along other specialists from the district to spend half a day at Anderson Elementary to observe classrooms, examine data, and engage in discussion with Gadson-Yarbrough and her assistant principal. The visit helped Gadson-Yarbrough frame priorities for her work in the coming months.

Many supervisors in Pipeline districts are now providing more direct support to principals.

The researchers studying the project quoted a principal in Gwinnett County on how the changes in evaluation, coupled with the change in the supervisor’s role, were playing out for him. He said he did not think of the process as “this big evaluation,” but rather as “an ongoing conversation all the time about what are your goals, how are you working toward those goals, and are you making progress or not. So it’s not sit down and have one meeting and be evaluated with feedback for next year because it’s an all-the-time conversation” (Anderson & Turnbull, 2016, p. 36).

Fine-Tuning the Process

Developing a new approach to evaluating school leaders takes time, as the six Pipeline districts have discovered. Typically, they went through “an initial year of pilot or partial implementation of a system, followed by (1) continuing fne-tuning of the principal standards in consultation with the state and (2) years of working with the principal supervisors who evaluated principals, aiming both to familiarize them with the system and also to use their feedback to improve the rubrics and procedures” (Anderson & Turnbull, 2016, p. 11).

Once familiar with the new evaluation materials, for example, supervisors often found gaps or ambiguities in language that the districts then sought to correct. In addition, the evaluations offered a reality check on the districts’ leadership standards, which in turn led to some rewriting—such as the Denver district’s decision to revise its standards to put more emphasis on the principal’s role in support for English language learners, a district priority (Turnbull et al., 2016).

An ongoing concern for the districts is what they call calibration—ensuring that the evaluators are all assessing their school leaders in the same way, with consistency and fairness in the evaluation ratings. A number of districts have sought to address this issue by giving principal supervisors calibration training. For example, the New York City district set up simulations in which groups of supervisors together looked at the same pieces of evidence for particular leadership practices and then gave their rationale for the ratings they would assign based on that evidence (Anderson & Turnbull, 2016).

An equally crucial concern for the districts is whether—and how—their principal ratings should account for situational factors that could affect a leader’s outcomes, such as experience level and the challenges of the school in which the principal was placed. Supervisors in several districts called for differentiation in the rubrics, arguing that it wasn’t fair to assess, say, a first-year principal or a principal in a high-needs school in the same way as a veteran principal in high-functioning school (Anderson & Turnbull, 2016).

Hillsborough is among the districts working to find a solution to this issue that won’t jeopardize evaluation consistency. McManus says the district wants to ensure in particular that principals who take assignments in high-needs schools don’t feel like they have been penalized for stepping into a tough, crucially important job—one where it can take three to five years to show significant improvements.

Regardless of the fine-tuning still to be done, Gadson-Yarbrough believes Hillsborough has come a long way in creating a helpful performance review. She recalls coming out of her evaluation last summer feeling confident in her areas of greatest strength— managing and developing people; culture and relationship building— and supported in another area, problem solving and strategic change management.

One goal she has set for herself to boost her performance in that capacity is to bring to Anderson Elementary the consistent use of an instructional fundamental: having teachers establish—and understand—the links between a learning objective, how it’s taught, and how it’s assessed. She has encountered some resistance to this from her staff—particularly to her suggestion that teachers post the learning objective at the beginning of a lesson and remind students of it periodically at appropriate moments.

The district hasn’t left Gadson-Yarbrough on her own to find a solution. At the monthly gatherings with other school leaders in her area, she has had opportunities to work out ideas with another principal tackling a similar issue. Gadson-Yarbrough’s supervisor has also jumped in, walking her through a series of questions about how to build faculty confidence in practices they may not be used to.

The upshot? Gadson-Yarbrough has decided to establish a stronger peer-to-peer learning system for her teachers— garnering good results so far. “I had a teacher facilitate the work instead of me,” she says. “I stood back a little and let the conversation flow with out mediating it so much. It felt much better. Everyone had a role.”

References

Anderson, L. M., & Turnbull, B. J. (2016, January). Building a stronger principalship: Volume 4—Evaluating and supporting principals. Washington, DC: Policy Studies Associates.

Portin, B. S., Feldman, S., & Knapp, M. S. (2006). Purposes, uses, and practices of leadership assessment in education. Seattle, WA: Center for the Study of Teaching and Policy, University of Washington.

Turnbull, B. J., Anderson, L. M., Riley, D. L., MacFarlane, J. R., & Aladjem, D. K. (2016, October). Building a stronger principalship: Volume 5—The principal pipeline initiative in action. Washington, DC: Policy Studies Associates, Inc.