Breadcrumb

- Wallace

- Reports

- Leading The Change Comparing The...

Leading the Change

Comparing the Principal Supervisor Role in 54 Districts

- Author(s)

- Ellen Goldring, Laura K. Rogers, and Melissa A. Clark

- Publisher(s)

- Vanderbilt University and Mathematica Policy Research

Summary

How we did this

This report presents findings from a 2018 survey of principal supervisors in the six Principal Supervisor Initiative districts and 48 other large urban districts. In total, 343 principal supervisors responded to the survey, including 50 in the six initiative districts (a 96 percent response rate) and 293 in the 48 other urban districts surveyed (a 64 percent response rate). The districts were all members of the Council of the Great City Schools, a coalition of the nation’s largest urban public school systems.

The need to remake the principal supervisor role has gained attention in recent years. Traditionally the role focused on administrative tasks. But principals need more support from their supervisors to improve teaching and learning and carry out an increasingly complex job.

In 2014, six large school districts around the country began major changes to the principal supervisor position. They refocused the role on supporting principals to improve classroom instruction. The Wallace Foundation funded the four-year effort, called the Principal Supervisor Initiative.

This report compares principal supervision in the six districts with principal supervision in 48 other urban districts. The goal is to show where the initiative succeeded or lagged behind broader trends. The report can also serve as a roadmap for other districts wanting to redesign the principal supervisor role.

The study finds that the initiative districts had more structures to buttress the reconceived job than other districts. However, supervisor practices across all the districts were similar. That could suggest districts nationwide are taking steps to change the job.

Strengths of Principal Supervisor Initiative Districts

The six districts participating in the initiative made structural changes to support the principal supervisor role. As a result, they showed these strengths compared with other urban districts:

- Principal supervisors in the six districts oversaw an average of only 13 principals. That gave them more time to work with each principal. Principal supervisors in other urban districts typically oversaw 16.

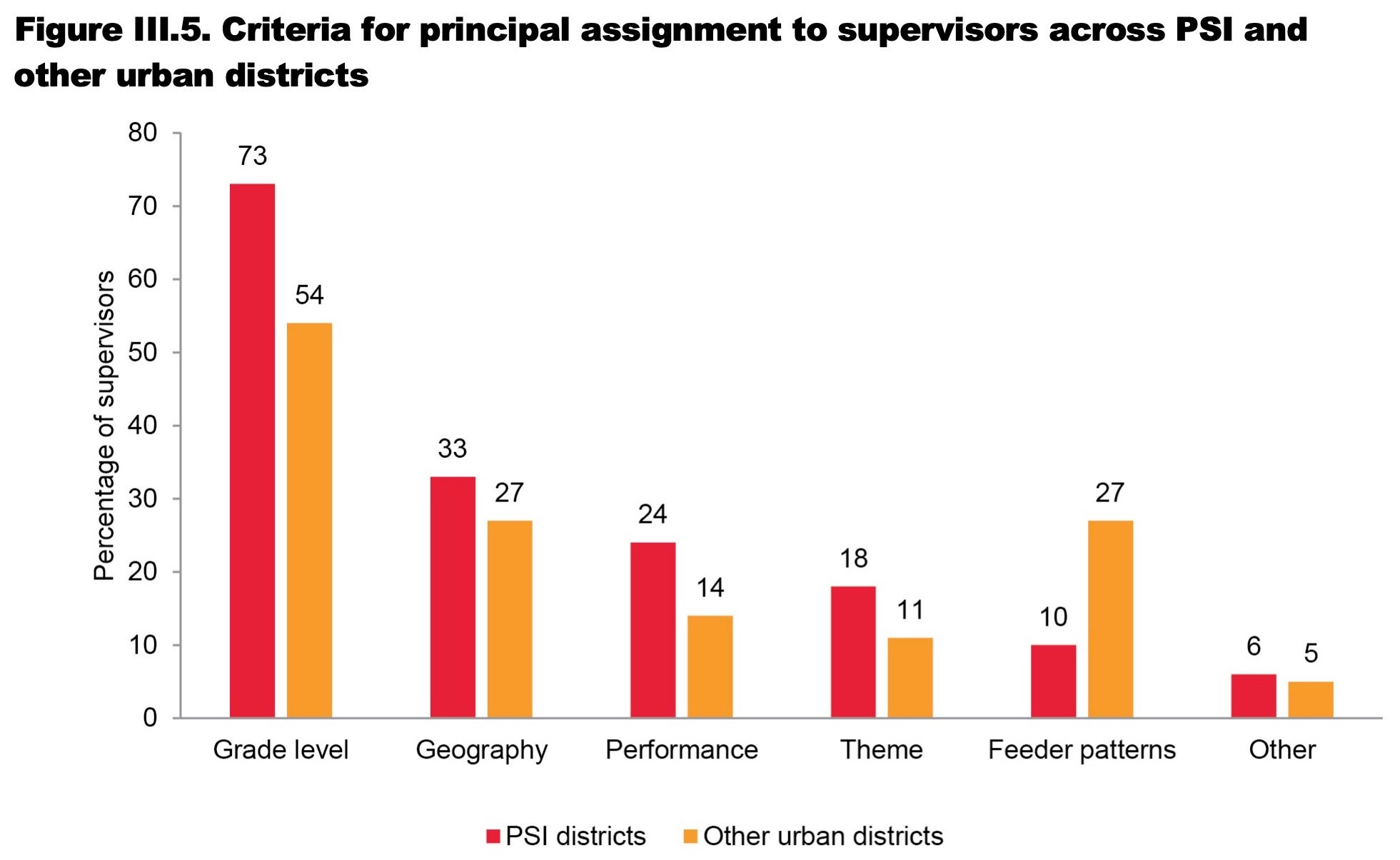

- In the six districts, principal supervisors were more likely to oversee a group of schools serving the same grade levels. They typically supported schools that were all either elementary, middle, or high schools. That allowed them to focus on a narrower set of content standards, curricula, and assessments. Supervisors in other urban districts typically lacked this advantage.

- Principal supervisors in the six districts were far more likely than their counterparts in other districts to report that they had sent instructional support staff to schools. (The difference was 71 percent vs. 41 percent.)

- Principal supervisors in the six districts rated their training more highly. The six districts were also more likely to offer programs for new and aspiring supervisors.

- In the six districts, principal supervisors rated their district’s supervisor evaluation systems more highly.

Similarities With Other Urban Districts

Districts participating in the Principal Supervisor Initiative had some strengths in common with other urban districts. Researchers thought this was because many urban districts were also redesigning the principal supervisor role. Principal supervisors in both sets of districts spent about 65 percent of their time working with principals. Half of the time with principals was devoted to instructional leadership. Supervisors in both sets of districts also used similar instructional leadership practices with principals. This included visiting classrooms and analyzing data.

Notably, principal supervisors from both groups of districts shared similar frustrations with their central offices. Overall, only about one third of principal supervisors surveyed agreed that their central office facilitates their work with principals. Strengthening central office support for principal supervisors was the most challenging part of the work for districts.

There needs to be a common language and theme within the district. Oftentimes departments are doing the same thing, but not talking with one another.

— Urban principal supervisor

The six districts participating in the Principal Supervisor Initiative were:

- Baltimore City Public Schools

- Broward County Public Schools, Fla.

- Cleveland Metropolitan School District

- Des Moines Public Schools

- Long Beach Unified School District, Calif.

- Minneapolis Public Schools

Key Takeaways

- Six large school districts redesigned the principal supervisor role to focus on supporting principals as instructional leaders. This report compares principal supervision in the six districts to 48 other large urban districts.

- The six districts made structural changes to support the principal supervisor role. Principal supervisors in those districts oversaw an average of only 13 principals. That gave them more time to work with each principal.

- In the six districts, principal supervisors were more likely to oversee a group of schools serving the same grade levels (elementary, middle, or high schools). That allowed them to focus on a narrower set of content standards, curricula, and assessments.

- Both groups of districts were working to improve the principal supervisor role. Principal supervisors in both sets of districts spent about 65 percent of their time working with principals. Half of that time with principals was spent on instructional leadership.

- Providing principal supervisors with sufficient support was challenging for districts. Only about one third of principal supervisors from either group of districts agreed that their central office facilitates their work with principals.

Visualizations