Is it feasible for districts to reconceive the role of those who supervise principals so less time is spent on compliance and more time on coaching to help principals strengthen teaching and learning in their schools? Is there an inherent conflict between supervising and evaluating principals and being a trusted coach?

A new Vanderbilt University–Mathematica Policy study offers answers to these questions by examining how six districts participating in The Wallace Foundation’s Principal Supervisor Initiative have reshaped the role.

The study concludes that in those urban districts — Baltimore; Broward County, Florida; Cleveland; Des Moines; Long Beach, California; and Minneapolis — it was feasible for principal supervisors to focus on developing principals. This important and complex work was done in less than three years and has resulted, to date, in principals feeling better supported. In addition, the role change has led to the districts’ central offices becoming more responsive to schools’ needs.

Principals felt better supported and saw no tension between the supervisor’s role as both evaluator and coach. The principal supervisor is a continuous presence in the school — a member of the community, not a visitor. Learning is continuous.

This role is relatively new on the scene — in fact, five years ago, there was no common term for it. Sometimes called principal managers or even instructional leadership directors, the people in these positions oversaw large numbers of principals and traditionally handled regulatory compliance, administration, and day-to-day operations.

They rarely visited a school more than once every few months and therefore did not work directly with principals. A 2013 Council of the Great City Schools survey of principal supervisors in 41 of the nation’s largest districts also identified other problems, including insufficient training, oversight of too many principals, mismatches in assignments to schools, and a lack of agreement about job titles.

Wallace launched the Principal Supervisor Initiative in 2014 to see whether and how districts could reshape the job. An important step was the development of the first-ever voluntary national model standards for supervisors in 2015, a process led by the Council of Chief State School Officers. These standards emphasize developing principals as professionals who “collaborate with and motivate others, to transform school environments in ways that ensure all students will graduate college- and career-ready,” rather than focusing on compliance with regulations. In the new study, the participating districts pointed to the importance of having standards for the job as a foundation for the position’s redesign.

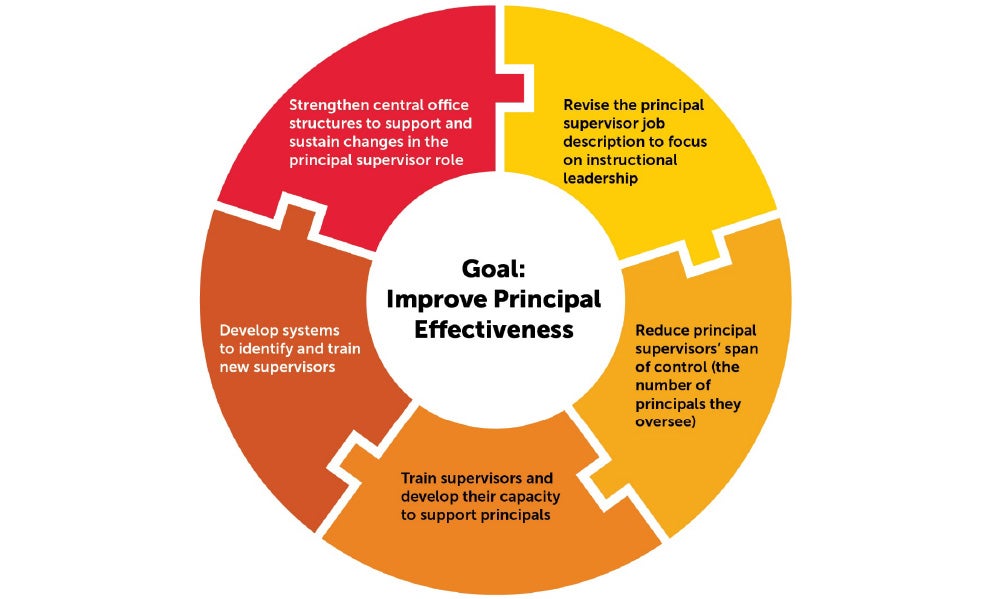

That study suggests that “substantial, meaningful change is possible” across five areas. “After three years, we saw substantial change in all districts,” says Ellen Goldring, the study’s lead author. “They came up with efficient and effective ways to position supervisors so they could fill the coaching and supporting gap.” Specifically, the districts:

- Revised principal supervisors’ job descriptions, relying on the national model standards that emphasize instructional leadership.

- Reduced the number of principals whom supervisors oversee by almost 30 percent, from an average of 17 to 12.

- Trained supervisors to support principals.

- Created systems to identify and train new supervisors.

- Restructured the central office to support and maintain the changed supervisor role.

Following the redesign, most principal supervisors in the six districts reported that they now spend most of their time — 63 percent — in schools or meeting with principals. This shift means supervisors are working directly with principals, engaging in new routines and practices, such as participating in classroom walk-throughs, coaching, leading collaborative learning, and providing ongoing feedback.

Across districts, the principals emphasized that they trusted their supervisors to function as both supporters and evaluators. As one Cleveland principal explained: “You don’t feel as though it’s your boss evaluating you. So it’s very comfortable. He’ll come in, he’ll have a conversation with you. … He always asks, ‘How can I support you? What do you need from me?’” It’s more of that than a formulated check-the-box.”

The districts also trained the supervisors to recognize high-quality instruction or better coach principals. For many, it was the first time they were provided with professional instruction specifically for their role. After two years, 80 percent of the supervisors reported participating in such opportunities.

In addition to offering professional development, districts began to identify more promising principal supervisor candidates and restructured central offices to support the new role and redistribute some noninstructional duties from supervisors to others in those offices.

Still, districts face some challenges. Goldring notes that the districts are continuing to refine the way they revamp the supervisor role, including defining what instructional leadership means, finding the right balance between supervisors’ time in school versus the central office, and providing uniformly high-quality training.

“It’s a heavy lift,” says Goldring. “But this study represents an incredibly positive example of the power of the supervisor role and a hopeful story about the power of district reform.”

Vanderbilt and Mathematica are planning two more reports to be published in 2019: One will measure the initiative’s impact on principal effectiveness, and the other will compare principal supervision in the six districts in the study with peers in other urban districts.

This article first appeared in The 74 Million and is reposted with permission.