What Do I Need to Know About Afterschool Systems?

Key Takeaways

Historically, the afterschool field has lacked coordination among the many hands involved in programming. The result is that children and teens often lack access to high-quality programs. This is especially true for young people with the greatest need.

Cities nationwide are trying to solve this by building systems to coordinate afterschool efforts and resources. In many communities, these systems cover summer and other out-of-school-time programs, too.

Studies have found that afterschool systems have notable benefits. They can increase access to programs, improve their quality, and foster better school attendance and other positive outcomes for students.

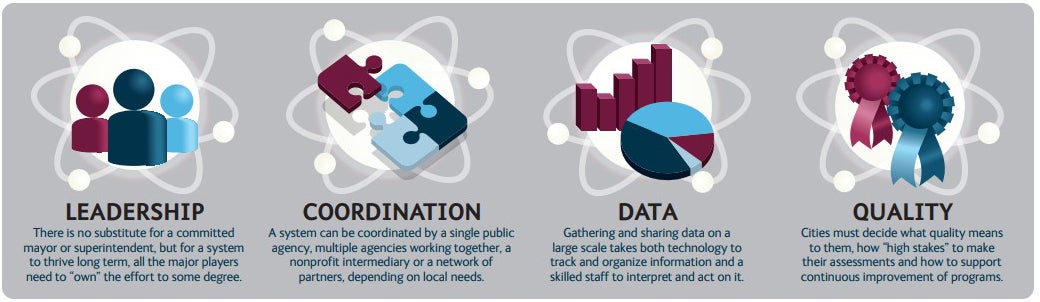

Afterschool systems have four key elements:

- Committed leadership

- Coordination that fits local needs

- Effective use of data

- A thoughtful approach to improving program quality.

Why Afterschool Systems Matter

Young people can benefit academically, socially, and emotionally from high-quality afterschool programs. Historically, however, the field has been disorganized. Programs work in isolation from one another and compete for funding from a patchwork of public and private sources. Civic leaders don’t always know much about the programs in their communities. As a result, the families that stand to benefit most from afterschool may not have access to it. The programs that are available may not be of the highest quality.

Afterschool systems bring together the major players in afterschool to coordinate their efforts and resources. These include city agencies, private funders, businesses, schools, and program providers. Afterschool systems serve a range of functions, such as:

- Identifying where program slots are most needed

- Raising and distributing funds

- Assessing the quality of programs

- Connecting program providers with training and coaching

- Communicating and advocating on behalf of programs

- Collecting and analyzing information.

Wallace’s Afterschool System-Building Initiatives

In 2003, Wallace began an initiative that eventually included five cities to help them build afterschool systems. The cities were Boston, Chicago, New York City, Providence, R.I., and Washington, D.C. At the time, system building was still a new idea. In the years that followed, interest grew. By 2012, Wallace was ready to launch a second initiative with nine other cities that had already begun to develop systems of their own. The focus of this second initiative was to help the nine cities improve program quality and collect and use data. Those cities were Baltimore, Denver, Fort Worth, Grand Rapids, Jacksonville, Louisville, Nashville, Philadelphia, and St. Paul.

There’s no greater gift than that kids have a safe, enriching, high-quality place to grow and learn all day. I mean, there’s nothing better that you can do.”

—David Cicilline, former mayor of Providence, R.I.

Benefits of Afterschool Systems

A 2010 RAND Corporation study looked at the five cities in Wallace’s first afterschool system-building initiative. The researchers developed case studies of each of the five efforts, based in part on interviews with key city leaders, leaders of community organizations, school principals, program providers, and others. This led to a cross-site analysis.

The big finding was that various organizations and institutions in a city can work together to coordinate afterschool services. In addition, systems can succeed in increasing access to programs and spur efforts to improve their quality.

A separate study, by Public/Private Ventures, found that afterschool systems can lead to positive outcomes for young people. Researchers looked at the AfterZone, an effort for middle school students developed by the afterschool system in Providence, R.I., the Providence After School Alliance. They focused on students who had participated in AfterZone programs during the 2008-2009 and 2009-2010 school years. The students, who were in sixth grade at the start of the study, experienced a range of benefits. These included more frequent school attendance than for students who did not participate in the program. The effect on attendance increased for students who took part in the program both years. These students also had higher math grades on average—by about one-third of a grade—than students who did not take part.

The findings were based on a sample of 763 youth from six middle schools. Information sources included surveys of the young people, administrative school records, and data from the Providence After School Alliance management information system.

Scores of U.S. cities have developed these systems. In 2020, they were more likely to have some key elements, such as quality standards or a quality framework, in place than they were in earlier years.

What can young people teach us about afterschool?

In a podcast, speakers include high school and college students who were part of a youth research team that studied what young people, especially from marginalized communities, want in afterschool programs.

The Key Elements of Afterschool Systems

Wallace’s afterschool system-building initiatives and a large body of research have helped identify four key elements of afterschool systems:

Committed leadership. There is no substitute for strong leadership from a mayor or school superintendent. At the same time, all major players, including families, need to “own” the effort to some degree.

Coordination that fits local needs. A system can be run by a single public agency, a nonprofit intermediary organization, or a network of partners depending on local circumstances.

Effective use of data. Systems need to gather and analyze data so they can make informed decisions. This requires technology to track and organize data. Systems also need skilled staff to interpret and act on the data.

A thoughtful approach to program quality. Cities must decide what quality means to them and support programs in meeting quality standards.

Featured Publications